Already a crisis in the U.S., fentanyl is now seeping into Tijuana’s drug supply

The fentanyl crisis that has claimed growing numbers of lives in the United States has been showing up on the streets of Tijuana, where intravenous drug users are often unknowingly injecting the powerful synthetic drug, according to a newly released research study.

While Mexico is more commonly portrayed as both a producer and corridor for fentanyl shipments bound for the United States, the study gives a rare glimpse into a developing consumption problem — and authors are hoping public policymakers will take note.

The 15-month study examined the deadly phenomenon of illicit fentanyl use that up to now has gone largely undocumented in Mexico. The report, published last month by the scientific journal Addiction, was spearheaded by Mexico’s National Institute for Psychiatry and Prevencasa, a Tijuana nonprofit that works with intravenous drug users.

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, is up to 50 times more powerful than heroin. Drug cartels have found fentanyl cheaper and easier to manufacture compared to the resource- and labor-intensive process of growing poppies and processing them into heroin.

The effort to document fentanyl use in Tijuana came after researchers began noting a spike in overdoses among intravenous drug users on Mexico’s northern border. Increasingly, these consumers have been switching from black tar heroin to a white powder sold as heroin that is referred to in Tijuana as “china white.”

“Two or three years ago, for every 10 locations where heroin was sold, eight were black tar and two were china white,” said Alfonso Chavez, one of the report’s authors and coordinator of Prevencasa’s needle exchange program. “There’s been an incredible transition. Now for every 10 sale locations, two are black tar and eight are china white.”

The drug users said the cost for a dose of the white powder was about 50 pesos, or $2.50 — equivalent to the cost of a dose of black tar heroin.

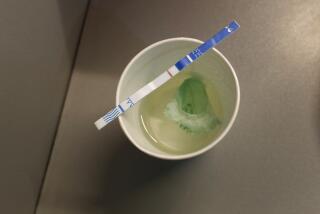

The study, conducted from May 2018 through July 2019, involved 89 heroin users who participated in the needle exchange program. The research team collected users’ drug paraphernalia weekly, testing for evidence of fentanyl on syringe plungers, metal cookers and drug wrappings.

In 59 of the samples, the users believed they were consuming pure heroin in white powder form, but the testing revealed that 55 contained fentanyl. Of nine samples of powder containing a mixture of heroin and crystal meth, all showed evidence of fentanyl. In five samples of white powder mixed with black tar, two contained fentanyl.

None of the pure black tar samples contained fentanyl, which “suggests that black tar is more difficult to adulterate, which could explain why the white powder presentation is replacing the black tar heroin that has been traditionally used in this region.”

During the course of their research, the investigators witnessed 20 overdoses during a six-month period. In all five of the cases where they were able to recover and test drug paraphernalia, they found evidence of fentanyl.

As its illicit use has dramatically increased in the United States, drug overdose deaths have shot up. Roughly 28,400 people died from synthetic opioid overdose, including fentanyl, in 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In San Diego County, 92 people died from fentanyl-related overdoses in 2018, with the rate of deaths growing in 2019.

Mexico has no such data. Most of the news stories involving fentanyl in Tijuana focus on seizures of contraband rather than tallies of local overdose deaths. San Diego has been by far the most common gateway for fentanyl seziures crossing the border.

With close to 2,200 homicides in Tijuana in 2019, the state medical examiner’s office has been overwhelmed. “They don’t have the resources to assign people to say “this person died from a fentanyl overdose, this person did not,” said Chavez of Prevencasa.

The study’s authors are hoping that their study draws the attention of policymakers and brings resources to the issue. Most urgent are supplies of naloxone — a medication that reverses the effects of an opioid overdose — for the city’s public hospitals and ambulances.

“More than being a research project, our hope is to have some impact on public policy,” Chavez said.

Dibble writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.