‘Mrs. Osmond’ takes up where Henry James’ ‘Portrait of a Lady’ left off but falls a bit short

“The house of fiction has in short not one window, but a million,” Henry James wrote memorably in his preface to “The Portrait of a Lady.” He added that the imposing structure of his 1881 novel was laid on a “single small cornerstone, the conception of a certain young woman affronting her destiny.” (That “affronting” — as opposed to “confronting” — is Exhibit A for what separates James from most writers.)

One hundred and thirty-six years later, Irish novelist John Banville — a consummate stylist himself whose books include the 2005 Man Booker Prize-winning “The Sea” — has dared with his 18th novel, “Mrs. Osmond,” a risky homage and sequel to “The Portrait of a Lady,” to pry open additional windows in the magnificent edifice that many consider the Master’s masterpiece. His goal is not to air out the musty rooms or freshen the place with a contemporary update but to climb in, make himself at home, and suss out what happened next to Isabel Archer Osmond, whose future was left hanging at the end of James’ novel.

While the ever-timely themes of women’s liberty and autonomy underpin both books, the two come at these issues from opposite angles. “Portrait” is largely driven by the marriage plot — the question of who this lively, imaginative, fiercely independent young woman will settle down with. But the focus in “Mrs. Osmond” is on a different sort of marital machination: Not who will marry whom, but the many ways in which women in bad unions — including Isabel — can extricate themselves and regain their freedom.

It’s almost a given that it’s impossible to live up to the source when taking on a classic.

It’s almost a given that it’s impossible to live up to the source when taking on a classic. Another danger is redundancy. While Banville’s many plot recaps assure that readers who haven’t read “Portrait” won’t be utterly lost, “Mrs. Osmond” feels more repetitive than fresh, particularly for those familiar with the original.

“Mrs. Osmond” takes up Isabel’s story shortly before James dropped it, two weeks after the death of her beloved cousin and benefactor, Ralph Touchett. Isabel, Banville reminds us, had rushed to Ralph’s deathbed in England from the aptly named Palazzo Roccanera, the black rock of a marital home in Rome on which her aspirations had been dashed. She had left against her husband’s wishes and on the heels of a devastating disclosure that explained the root of her marital woes.

We meet Banville’s Isabel shortly after she leaves Ralph’s home, Gardencourt, a much-changed person from when she’d landed there fresh from Albany, N.Y., six years earlier. Unmoored after the loss of the person who cherished her most, she is tormented with the question of her next move. Should she go back to her contemptuous husband, Gilbert Osmond? Should she sacrifice her fortune to buy her freedom? Banville writes, “What was freedom, she thought, other than the right to exercise one’s choices?”

While Banville’s many plot recaps assure that readers who haven’t read “Portrait” won’t be utterly lost, “Mrs. Osmond” feels more repetitive than fresh.

Banville channels James’ celebrated interiority to capture Isabel’s vacillations and self-lacerations as she asks herself how could she have been so blind, weak and naïve to have fallen for the insidious trap laid by Madame Merle and her longtime lover, Osmond — the very question readers asked while watching Isabel head toward her doom in “Portrait.” But, despite some abstruse Jamesianisms like “instauration,” “peculation,” “invigilator,” and — my favorite — an “inspissatedly expressed and barely scrutable conjecture,” he tempers his stylistic mimicry to appeal to modern tastes, with shorter paragraphs and heightened urgency. Yes, there are fewer complicated sentences to slow you down, but also fewer astonishing insights to arrest your attention.

By the time we meet her in “Mrs. Osmond,” Isabel has lost much of her spark, though Banville reassures us that “she was no sanguinate martyr.” To keep us turning pages, he teasingly withholds revelations and shamelessly dangles narrative carrots about tightly held secrets bound to wreak further damage on one character or another. Some plot twists come courtesy of welcome new characters, including Isabel’s fiercely loyal maid, Elsie Staines, and a dying suffragist, Miss Janeway. Others, like a bizarre suggestion of lesbianism, land with headshake-inducing thuds.

The novel is full of evasive confrontations, as Isabel repeatedly stops short of baring her soul, wondering “what was to be gained by undoing all at once the stiffened rags in which her wounds were wrapped.” Banville adds, “She had concealed those wounds for so long, for years and years, thinking it her duty to suffer in silence, but what if that reticence were only another mark of her arrogance, her overweening self-regard?” (Years and years? Hadn’t she been married for fewer than five?)

Banville more effectively captures the warped dynamic of the miserable mismatch between Isabel and Gilbert, with the “refined yet savage stalking of each other that their marriage had become.” But he also amplifies the histrionics, particularly when describing how Isabel’s tenacious American suitor Caspar Goodwood “had grasped her in his electric embrace and branded her with a kiss.” Banville’s prose goes positively purple with “the heaped pyre of possibilities it had set alight inside her.” The kiss, we’re told, “consumed all oxygen, and set her staggering backwards, clutching at her throat and gasping for breath.” Henry James, it appears, has been defenestrated.

What effect does this “transforming fire” have on Isabel’s life? Stay tuned. While “Mrs. Osmond” does indeed answer questions that remained at the end of what James called his “ado about Isabel Archer,” Banville, too, has left plenty of windows open to this vivid, strong-willed heroine’s next chapters.

In addition to The Times, McAlpin reviews books regularly for NPR, the Washington Post, San Francisco Chronicle and other publications.

John Banville

Knopf: 384 pp., $27.95

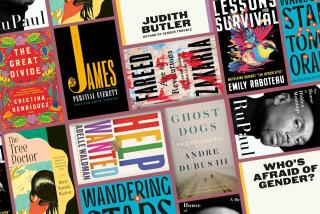

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.