‘Eccentric Orbits’ chronicles the stunning failure (and improbable revival) of the Iridium satellite phone

The business sections of bookstores overflow with guides to success — the presumptive GOP presidential nominee, for instance, has stamped his name on more than a dozen of them. The business books worth remembering, though? Those tend to be about failure.

Think of “Final Cut,” Steven Bach’s gripping account of the notorious movie disaster “Heaven’s Gate.” Or “The Smartest Guys in the Room,” Bethany McLean and Peter Elkind’s chronicle of the collapse of Enron, and “The Big Short,” Michael Lewis’ tale of the cratering of the national economy.

“Eccentric Orbits,” John Bloom’s offbeat history of the Iridium satellite phone, is a kind of biz-book twofer. Its first half is a tale of ham-fisted management that’s lively enough to invite comparisons to those modern classics about failure.

What if a $6 billion company opened for business — and nobody came?

— From ‘Eccentric Orbits: The Iridium Story’

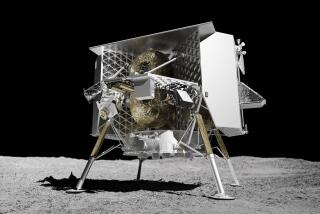

But because Iridium was only a near-failure and not a total one, it’s also a peculiar — and drowsier — turnaround story. As the leading maker of satellite phones, Iridium today covers all the blank spots in cellphone coverage maps. Its phones have saved mountain climbers, assisted first responders during the 2010 Haiti earthquake, and connected far-flung researchers, pilots and ship captains. Navy SEALs love them; so do terrorists.

In 1999 the company was a bankrupt laughingstock, and tech giant Motorola was prepared to literally torch its network of dozens of low-orbiting satellites. Iridium’s minders were dubbed “Iridiots” by people in their own company, and not without reason.

Author Bloom is an investigative journalist with an alter ego, Joe Bob Briggs, the down-home B-movie enthusiast from the Movie Channel with a taste for oddball stories. He has a doozy here.

Iridium was conceived in the late 1980s by a handful of employees stationed in “Motorola Siberia” — Chandler, Ariz., a Phoenix suburb where the company handled sensitive military contract work. (Motorola’s main headquarters were near Chicago, a top nuclear-strike target.) Building on the technology behind the Reagan-era “Star Wars” anti-ballistic missile system, the Chandler team invented an elegant network of 77 interconnected satellites orbiting the earth, effectively transforming the entire lower atmosphere into an always-on cell tower.

The book’s title directly refers to the unusual calibrations required to keep the satellites from crashing into each other. But it’s also a good shorthand for a motley crew of characters and incidents awash in human foible.

Iridium was approved by a global regulatory group only because the lead protesters were napping during a vote. Its girthy handset resembled “a Dumpster on a Mercedes engine” and “a brick with a baguette sticking out of it.” The phone itself cost $3,795, and calls could cost upward of $4 a minute. Then-Vice President Al Gore, a fan of all new technologies, made a symbolic first call to a descendant of Alexander Graham Bell, but the man on the other end “couldn’t understand a thing he was saying.” Early on, Iridium reception could be spotty in places where there were ceilings, say, or walls.

Iridium’s biggest problem, however, was Motorola’s weak management back on Earth. Phones were marketed to wealthy early adopters who were more seduced by the sleek new flip phones sold by … Motorola. Iridium’s hard-nosed CEO, Ed Staiano, alienated employees by canceling vacations in desperation to meet a fall 1998 launch date. And the company made an impossibly huge bet: With a $6-billion investment, it needed a million customers in its first year to stay afloat. By January 1999 it had 3,637. Iridium filed for Chapter 11 after nine months in business — at the time the largest bankruptcy in American history.

Bloom takes this story seriously, but as the business hurtles toward disaster he also writes with a winking awareness of the absurdity of Iridium’s predicament. After covering the fanfare of Iridium’s official launch day, Bloom shifts his camera to a sole employee monitoring first-day phone usage. The depth of the failure slowly dawns on him. “He suddenly realized — those were all test calls. Those were all either free phones or calls being made by Iridium employees. What if a $6 billion company opened for business — and nobody came?”

Enter Dan Colussy, perhaps the most unlikely figure in a story full of them. A Coast Guard vet and former head of Pan Am, Colussy was 69 and retired when he had a notion to rescue Iridium after seeing one on a trip to the Panama Canal. He needed about $200 million, and fast — Motorola made constant threats to “de-orbit” the satellites, to send them to fiery oblivion in the atmosphere, hopefully without stray pieces of flaming space junk landing on populated areas.

Within months he’d assembled a patchwork group of investors that included Boeing, a secretive Saudi prince, various global telecom firms, and Herb Wilkins, a lead investor in Black Entertainment Television, who saw Iridium as a potential lifeline for Africa. Up until then, Wilkins had preferred to keep his investments in black communities, but he liked Colussy’s style. “You’re not gonna believe this,” Wilkins told a colleague, “but for the first time in my life, I’m gonna back a white man.”

And all the while, Colussy had to satisfy the demands of the Pentagon and government staffers who needed to sign off on any deal — a group that included seemingly every federal agency except the National Endowment for the Arts. It’s a remarkable feat of corporate brinkmanship that raises a question “Eccentric Orbits” doesn’t satisfyingly answer: Who the heck is Dan Colussy?

Bloom had plenty of access to Iridium’s savior, as the author’s note explains, but his character and leadership style remains somewhat inscrutable. He has “an affable manner reminiscent of Jimmy Stewart,” Bloom tells us, and that his wife was disappointed in his un-retirement. But there’s little about his motivations for pursuing Iridium with such intensity. He hated to lose, Bloom tells us, but what CEO doesn’t? During his Pan Am days, we learn, he acquired an ambition to own a company and not just lead it. But surely there were easier companies to own.

This lack of human scale is a weight on the book’s second half, in which byzantine tangles of deals come together, collapse, then re-form in slightly different shapes. A full page is given to another businessman’s frustration over a lost briefcase; if only so much real estate were dedicated to Colussy’s strategic thinking.

What’s clear enough is that Colussy was temperamentally well-suited to save Iridium. He was willing to listen to anybody — including investors like Wilkins who were used to being ignored — and could make nice with hot-tempered execs like Staiano. Because Motorola’s main concern was being indemnified from any potential damage from the de-orbited satellites, Colussy knew the company’s threats to crash the system were largely bluster. Luckily, the Pentagon helped buy him time. “I hear one more . . . threat to bring these satellites down, then [Motorola] is going to have a really hard time doing business with the Pentagon in the future,” barked one exasperated member of the military brass.

Legendary Motorola CEO Bob Galvin had two mantras for his employees. “Do not fear failure!” was the first. “Recognize the signs!” was the second — that is, signs of failure. The first mantra helped spark Iridium, a complex and innovative idea brought to life by a few guys in Motorola Siberia. The second mantra almost killed it in spectacular fashion.

But Iridium sold in 2008 for $591 million. “The most complicated satellite constellation ever devised was saved because of the persistence of a single man,” Bloom writes. That’s a remarkable feat — and a fuller story about the man who pulled it off would make for a rare remarkable book about success.

Athitakis is a reviewer in Phoenix.

::

“Eccentric Orbits: The Iridium Story”

John Bloom

Atlantic Monthly Press: 560 pp., $27.50

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.