Review: ‘The Short and Tragic Life’ explores class, race amid struggle and wonder

There’s one word in the title of Jeff Hobbs’ new biography of his friend Robert Peace that doesn’t quite belong there: “tragic.”

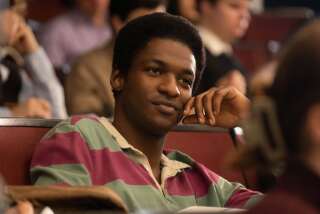

“The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace: A Brilliant Young Man Who Left Newark for the Ivy League” tells the story of Peace, the son of a cash-strapped single mother. Hobbs met Peace when both were students at Yale. Nine years after they graduated together, Peace was shot and killed in Newark.

To reduce Peace’s 30-year existence to a single adjective derived from Greek drama does a disservice to Peace, however. It’s also unfair to Hobbs’ book. Robert Peace was, in his friend’s telling, a force of nature. Peace’s death may have been tragic — and also senseless. But in life he was intelligent, resourceful, creative and successful beyond his wildest dreams.

Despite the baggage of a childhood in an especially grim corner of Newark and of a father in prison, Peace triumphed at Yale. He did so in a field whose very name sounds daunting: molecular biophysics and biochemistry. At the same time, he was a real-life version of the protagonist of “Breaking Bad.” He was an educated and cultured man who kept himself and his family afloat by dealing illicit drugs.

“He simply went to class, did his work, got A’s,” Hobbs writes of Peace’s time at Yale. “That he did so while smoking (and dealing) copious amounts of marijuana only made him more of a marvel; he wasn’t just smart, he was cool.”

Hobbs wrote the novel “The Tourists,” and he gives his account of Peace’s life a suitably novelistic beginning. He starts with Robert’s birth to the free-willed Jackie Peace in Newark in 1980.

Jackie brings baby Robert (who will soon be known as Rob) home for the first time, driving through Newark on a “swampy” June night. “The last of the neighborhood children had been called inside to clear the way for the hustlers who governed much of the greater Newark, New Jersey, area, and particularly this township of Orange, during the wilderness of the nocturnal hours.”

Hobbs has worked hard at researching the details of Rob’s early life. And he conveys Rob’s childhood with great compassion. Rob’s mother and father lived in the community with “the second highest concentration of African Americans living below the poverty line in America,” Hobbs says. But Jackie provides both love and learning and reads frequently to the boy. By the time Rob reaches daycare, his teachers have already started to call him “The Professor” because “he knows everything.”

Rob’s father is at once charismatic (he’s a popular neighborhood drug dealer) and largely absent. He plays an intermittent but important role in his son’s early life but is then arrested and charged with a drug-related double homicide.

Unfortunately, while Hobbs might be thinking like a novelist in these critical first two sections of his book, he doesn’t always write like one. His account of Rob’s childhood is stilted and stiff, often peppered with odd abstractions that drain the life from his narrative.

How is it, for example, that Rob can feel at home in both the uptight, strait-laced world of his Catholic prep school and in his freewheeling, gritty and violent neighborhood? Hobbs writes that Rob uses “neural switches” and “calibrations of behavior” to navigate between both places. And when Rob goes home and talks to his mother about school, Hobbs says he is “rendering his day” to her. “This existence was fracturing, but it was the only way to integrate his ambition and intellect in a milieu in which neither had currency and in which both could get him hurt,” Hobbs writes.

It’s as if Hobbs, a white man, felt he didn’t have the right to fully inhabit the story of his African American subject.

But “The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace” comes alive from its third section onward, after Hobbs meets Peace at Yale. For the following four years, the two young men remain roommates, housemates and unlikely kindred spirits.

The men, black and white, have been thrown together into the competitive, status-conscious and often soul-crushing social environment of an Ivy League school. Both can see through the pretense around them — or “fronting,” as Peace calls it. But it’s harder for Peace to take because he’s grown up among people who value authenticity above all else.

After a humiliating encounter with three members of the Yale crew in a university cafeteria, Peace seethes with anger. He longs to prove to the “entitled” crew members that “no one was invincible” and that “Yalie or not, anyone could and should be held to account” for their treatment of others. “I got the sense that where he’d grown up, this wasn’t a matter of etiquette or debate,” Hobbs says.

Hobbs and Peace went their separate ways, for the most part, after they graduated. The last nine years of Peace’s life must have been difficult to piece together, but Hobbs has done an outstanding job of research. Peace eschews a career after graduating and travels the world, teaching himself Portuguese to live in Rio. Hobbs also reconstructs, with intimate detail, the drug deals and betrayals that will eventually lead to his old friend’s downfall. Peace dies selling a drug (marijuana) that in the years since has gained a much larger measure of societal acceptance.

In the end, “The Short Tragic Life of Robert Peace” is a book that is as much about class as it is race. Peace traveled across America’s widening social divide, and Hobbs’ book is an honest, insightful and empathetic account of his sometimes painful, always strange journey.

Peace’s desire to define happiness on his own terms ultimately led to his undoing. But his life was also filled with wonder, and living it required courage and fortitude, qualities he possessed in great abundance.

Tobar is a former Times reporter and author of the forthcoming book “Deep Down Dark.”

The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace

A Brilliant Young Man Who Left Newark for the Ivy League

Jeff Hobbs

Scribner: 406 pp., $27

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.