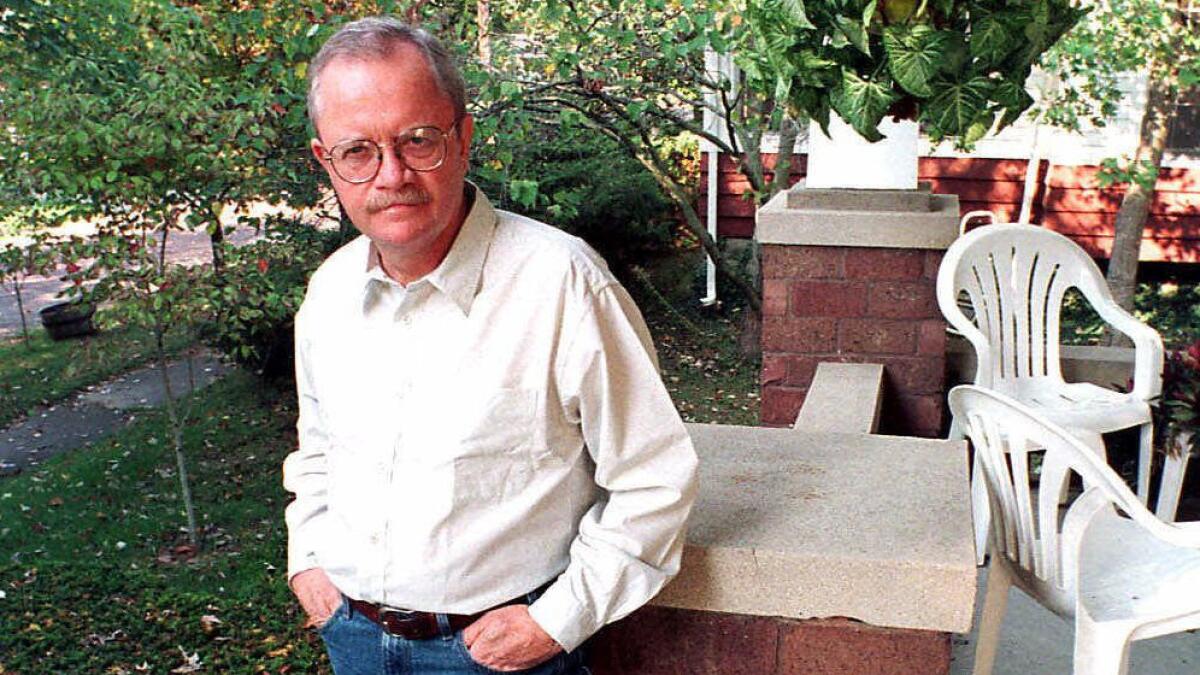

Novelist Kent Haruf has died at 71

Kent Haruf, the Colorado writer whose 1999 novel “Plainsong” was a finalist for the National Book Award, died Sunday at age 71, his publisher Knopf has announced. He had been battling cancer, and recently completed his sixth novel, “Our Souls at Night,” which will be published in 2015.

Haruf was something of a late bloomer; his first novel, “The Ties That Bind,” did not come out until he was 41. In that book, he established the fictional town of Holt, on “the high plains of eastern Colorado,” a composite of the three small villages in which he was raised. In an essay called “The Making of a Writer,” published in the most recent issue of the journal Granta, Haruf described the effect of growing up in such a setting.

“And of course,” he wrote, “it was those towns and that landscape and the culture of that specific place which has had so much influence on me and my writing. During that period of my life out on the high plains, I was more or less a happy kid, I think, and I survived childhood with only a few hard lessons that I still remember. One was: don’t you be a show-off, and I have tried to abide by that injunction ever since, with all its contradictions and complications.”

That’s a pretty good accounting of Haruf’s aesthetic, which was spare and no-nonsense, portraying a world in which certain verities remain. That’s the point of Holt, a town that exists out of time in many ways, although time (as it must) can’t help but make its effects known.

In “Plainsong,” inspired by Sherwood Anderson’s 1919 short story cycle “Winesburg, Ohio,” the narrative rotates through a series of characters and plot lines, always coming back to a central unity, which is, of course, the life of the town itself. “Benediction,” published in 2013, deals with the arrival of a new preacher and the fallout from his politics.

This may be the timeliest of Haruf’s novels, in the sense that it deals with the aftermath of 9/11 and the territory of gay rights. But the essence of his fiction is that timeliness may be our most fundamental illusion, that, in essential ways, life unfolds as it has always, with the rhythms of the small town and the plains.

Haruf was a trenchant observer of his own process, observing of “Our Souls at Night,” which he wrote this past spring and summer, that “[i]n some ways it feels as if it kept me alive.”

That’s a vivid testament to art’s power to sustain us, even (or especially) when we cannot be sustained.

Or, as Haruf observes in “The Making of a Writer”: “You have to believe in yourself despite the evidence. I felt as though I had a little flame of talent, not a big talent, but a little pilot-light-sized flame of talent, and I had to tend to it regularly, religiously, with care and discipline, like a kind of monk or acolyte, and not to ever let the little flame go out.”

twitter: @davidulin

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.