Father Gregory Boyle, author of new book, to Pasadena audience: Consider radical kinship and compassion

Father Gregory Boyle is a fan of Freudian slips. Even the smallest, unintentional miswording can be instructive, he says.

Addressing the packed pews of All Saints Church in Pasadena on Monday night, he recalled an instance when an eager young man had misread “The Lord is exalted” as “The Lord is exhausted” during a service.

“I remember thinking at the time, wow, that’s better,” he said. The audience, who was there not for mass but for a signing of Boyle’s new book, “Barking to the Choir: The Power of Radical Kinship,” laughed.

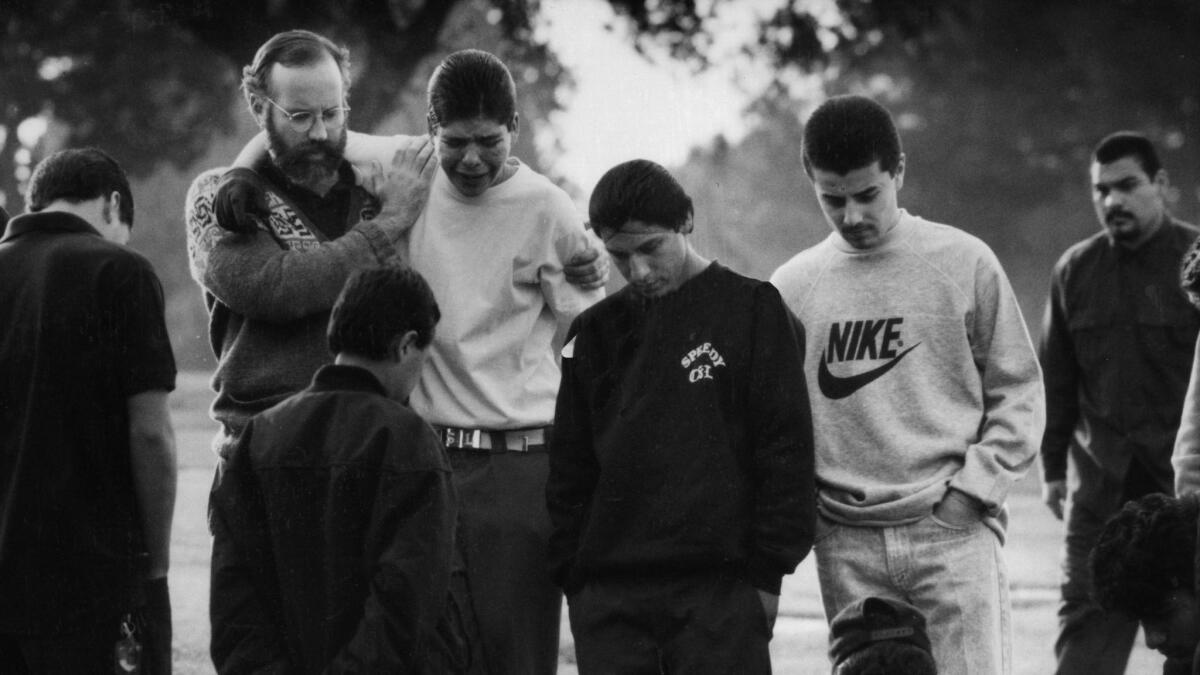

It was one of many anecdotes — some humorous, some heartbreaking — that Boyle wove through a talk on his life’s work and philosophy. The Jesuit priest is a longtime activist in Boyle Heights and founder of the nonprofit Homeboy Industries, which provides former gang members paths out of that life. Rather than read from the book, his second, he delivered an almost secular sermon.

Boyle became the pastor of Dolores Mission Church in Boyle Heights in 1986; at the time, it was the poorest parish in the city. During an era of intense gang violence in Los Angeles, he created Homebody Industries, which provides job preparation and placement, tattoo removal, mental health and legal services and a wide variety of other support. “Barking to the Choir” tells the stories of some of the young men and women with whom Boyle has worked and invites readers to allow kinship and compassion into their lives.

In an appearance on NPR’s “Fresh Air” in November, Boyle told host Terry Gross that he’d recently gone through immunotherapy and radiation to treat the leukemia he was diagnosed with more than a decade ago. When she pressed him about his cancer, he said, “my health has never been kind of on my top 10 list of things I ever worry about.” Instead, he used his time on the program to turn attention back to the young people with whom he works.

In Pasadena, he said, “I think you’re here tonight because you long for other voices to be heard … not mine, but the voices on the margins.”

Boyle described two men from rival gangs who became friends through Homeboy Industries.

“They used to shoot bullets at each other,” said Boyle. “Now they shoot texts.”

He also told the story of a boy who wore three shirts to school because blood had soaked through the first two where his mother beat him, and of the forgiving, compassionate man he’d become.

“The homies have taught me if you don’t welcome your wounds, you may be tempted to despise the wounded,” Boyle said.

Boyle took questions from the crowd. One came from 9-year-old Julia Roe: Did he have any stories that made him feel emotional?

“You want me to get emotional?” Boyle asked. The crowd laughed, but Boyle took the girl’s question seriously. Once, after the funeral of two victims of gun violence, he thought he was alone in his office and began to break down. A homie named Chico came in, “he was very tender,” and told Boyle that if in that moment “somebody offered me a million dollars or the chance to swoop you up, I’d swoop you up,” Boyle said, his voice breaking. “If love is the answer, community is the context. Tenderness is the methodology … tenderness is the way.”

Maria Elena Roe, Julia’s mother, described Boyle’s appeal as “a new perspective from what you’ve heard in church before.” She and her husband attended the event because they want to expose their children to his story. For her part, Julia said she posed her question to Boyle because “I know everyone has a soft spot” and that when he told stories about people losing their family to violence, she wondered, “How would it feel?”

Over the course of the evening, Boyle kept returning to one theme: He doesn’t bring faith to gang members, it’s gang members who bring faith to him.

“We don’t go to the margins to make a difference,” he said, “we go to the margins so that folks at the margins make us different.” Delivering a message, adopting a savior mentality, is wrongheaded. “Saving lives is for the Coast Guard,” he said.

Sara Corralejo, a student at the University of La Verne, came to the event to meet Boyle.

“Seeing how many things he’s actually done gives you motivation,” she said, the sense that “it’s possible to reach people who have been through a lot.” That the audience was mostly upper-middle class and white interested her. She thought the demographic may have been why Boyle had reiterated that people on the margins can have an impact on you as much as you can on them.

When did Boyle know that gang intervention would be his life’s work? “I don’t know if I have aha moments. I have more, huh?” he joked, before explaining, simply, “You go where the life is.”

For the last 30 years, Father Gregory Boyle and Homeboy Industries have been supporting and training formerly incarcerated and gang-involved individuals in East L.A. Former gang members reveal their process of healing.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.