What a big Ed Ruscha exhibition misses about Southern California

“I’m interested in glorifying something that we in the world would say doesn’t deserve being glorified,” Ed Ruscha told the Guardian’s Leo Benedictus in 2008.

Ostensibly he was speaking only about the household objects, corporate logos and generic architecture he has featured in his paintings for more than five decades, beginning with “Box Smashed Flat (Vicksburg),” a canvas from 1960-61 that includes a spread-eagled container of Sun-Maid raisins in its upper half.

But he could just as well have been referring to his early work and its relationship to Los Angeles, the city that has inspired, given easy cover to and marked the shifting epicenter of his artistic output since he moved here in 1956.

I’ve been thinking about that relationship quite a bit since walking through a major new exhibition on the artist at the De Young Museum in San Francisco. Curated by the museum’s Karin Breuer and titled “Ed Ruscha and the Great American West,” the show includes a number of pieces pulled from the De Young’s own extensive collection of the artist’s work. It runs through Oct. 9.

To the extent that the exhibition tries to clarify the role of Los Angeles and its architecture in Ruscha’s paintings and photographs — and it is impossible to explore that work in any depth without bumping directly into the subject of L.A. — it never finds a sharp focus.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Perhaps in an effort to make the show more attractive or accessible to Northern Californians, Breuer has lumped a huge and diverse collection of pieces together as representative of Ruscha’s response to the “American West.” Both the catalog and the exhibition’s audio guide benefit from the thoughtful and unflappable presence of the Southern California writer D.J. Waldie, who repeatedly draws the show back from the brink of easy and superficial readings of Los Angeles. But to think of Northern California’s relationship to the idea of the West as running parallel to L.A.’s, or of Ruscha’s view of the region as big or flexible enough to extend north of the Grapevine, is an assumption that knocks the exhibition off-stride from its opening rooms.

Ruscha remains an elusive artist and Los Angeles an elusive city, each of them slippery to the last.

As Reyner Banham put it in 1971 in “Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies,” while San Francisco “was plugged into California from the sea … Southern Californians came, predominantly, overland to Los Angeles, slowly traversing the whole North American land-mass and its evolving history.” This is a show that layers a plugged-in view of California and the West atop an overland one.

Ruscha is in every way one of the overland Californians. He reached Los Angeles by driving west from Oklahoma City with his friend Mason Williams at age 18 to enroll at the Chouinard Art Institute, the school that would later become the California Institute of the Arts.

This trajectory shaped his work from then on. Los Angeles was for Ruscha not an emerging Pacific Rim economic power or a rival to San Francisco (or New York, for that matter). It was a more idyllic and ultimately more compromised version of the landscape stretching between Barstow and the Oklahoma border.

Like Carey McWilliams before him — as well as Banham and architects Frank Gehry and Denise Scott Brown a bit later — Ruscha found in Los Angeles a quickly growing city that as a subject for artistic or cultural study was deeply underexplored. In paintings and a series of photography books, he set about both cataloging the architecture of the city with a deadpan eye and taking advantage of its blank-canvas reputation to further his own artistic one. He treated Los Angeles itself as a readymade.

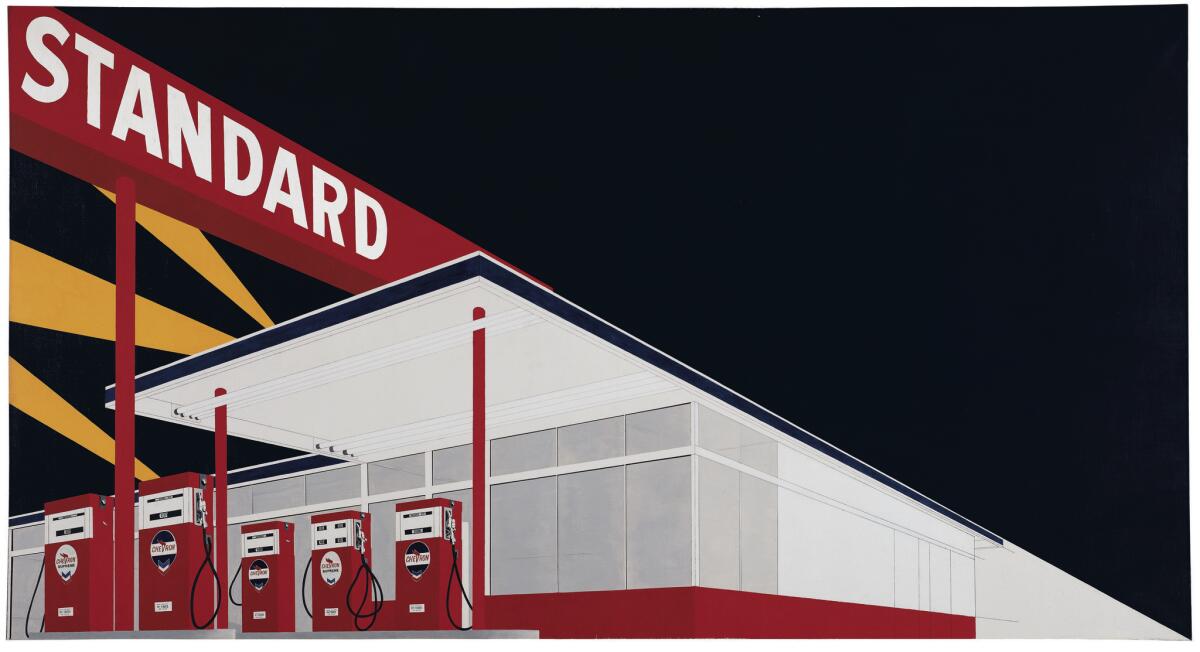

Much has been written, by the critic Dave Hickey and others, about how Ruscha used images of buildings on fire to advertise his own intent to torch existing expectations about the role of painting in postwar America — not to mention divisions between abstraction and realism, depth and flatness, still life and landscape and high and low culture. He did so as early as 1964 with paintings showing hamburger joints and gas stations — with names like “Norms” and “Standard,” get it? — in flames. One of the gas-station paintings is in the De Young show.

Somewhat less of interest has been said about the particular urban character of the Los Angeles Ruscha depicts in paintings like those and in the photo books “Some Los Angeles Apartments” (1965), “Every Building on the Sunset Strip” (1966) and “Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles” (1967).

These aren’t just affectless attempts to document the built environment of Los Angeles as seen from the boulevard (“Every Building”) or a helicopter (“Parking Lots”), a first stab at a taxonomy of the postwar cityscape. They also capture, with surprising affection, the public spaces of a city whose civic realm was rapidly being drained and denuded as more and more investment and architectural energy poured into the private realm of the single-family house and the freeways being built to serve new subdivisions. They show a landscape entirely free of people: a city without a public.

In this sense Ruscha’s work, at least when it considers the architecture of Los Angeles, is the tight-lipped twin to Julius Shulman’s glamour shots of mid-century domestic interiors here, the most famous of which are peopled with charismatic figures, models dressed and arranged on the furniture by Shulman himself.

The emptiness of Ruscha’s images points to what may be the central and animating paradox of his career: that his work, as closely linked to one region as that of any American artist of his generation, is grounded in a city whose postwar public spaces promoted a profound dislocation and alienation.

Nearly every marker of his regionalism, every bit of evidence of his steadfast dedication to exploring Los Angeles and Southern California, has elements of the generic or the universal. (Again, norms and standards.) He is at home in a place known — at least in its civic realm, where he focuses his artistic gaze — for placelessness. Perhaps no painting in the show sums up this contradictory attitude as well as a 2014 work called (and featuring the words) “God Knows Where.” If He does, so does Ruscha.

There is also the question of how Los Angeles has changed since 1956 and how Ruscha’s own feelings about the city have evolved. If Ruscha (like McWilliams, Banham and Gehry) found Los Angeles unsullied by over-analysis when he started making work here, these days the opposite is true. (As the novelist James Ellroy points out in a perceptive essay in the catalog for a 2010 Ruscha show organized by the Hayward Gallery in London, L.A. was “comparatively unscrutinized” when Ruscha arrived but in the years since “has become the most overscrutinized city on earth.”)

“Ed Ruscha and the Great American West” sticks to a largely pat reading of L.A. and Ruscha’s feelings about its maturation, a reading that acknowledges a certain loss of innocence but doesn’t dwell on it. “The roads he loves still lead west, where he continues to find fertile ground,” Breuer writes cheerfully at the end of her catalog essay.

For me that weakness provides a perverse sort of hope: Ruscha remains an elusive artist and Los Angeles an elusive city, each of them slippery to the last. I admire how often and easily both foil those who mistake their bright, flat surfaces and guileless manner for superficiality or lack of substance.

Breuer saves a prominent spot in the second-to-last room for a 1984 canvas that features a blue-sky background beneath the words “Honey….I Twisted Through More Damned Traffic to Get Here” — a piece that may say as much about Ruscha’s own working through of certain art-history dogmas and expectations as it does about Los Angeles. It is the kind of painting that gives San Franciscans an easy chuckle at the expense of Angelenos trapped on the 405 but tends to suggest to attentive Angelenos a different kind of traffic, one connecting Southern California to (and sometimes keeping us estranged from) received ideas about architecture, urbanism and art history.

The notions about Los Angeles that animated and complicated Ruscha’s work in the early decades of his career — that this is a city of cars and smog and an abandoned civic realm — seem increasingly out of date. The surface parking lots that were mushrooming when Ruscha photographed them, for instance, colonizing bigger and bigger swaths of the city, are beginning to disappear, especially in parts of the city like downtown and Koreatown. I say this with all seriousness: We may soon need a preservation movement in Los Angeles in service of certain parking lots.

The air meanwhile hasn’t been smoggy enough in years for an artist to get away with a pun, as Ruscha does in his famous 1983 work “A Particular Kind of Heaven,” pairing the specific nature of his attraction to Los Angeles with the pollution — the particulates — responsible for the beauty of the sunset that makes up the painting’s backdrop.

Ruscha, for his part, has responded to the emergence of an increasingly public and more crowded Los Angeles with more than a little grouchiness. “I’m not ready for a new millennium,” he tells Kerry Brougher, director of L.A.’s Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, in an interview in the De Young catalog. “I’m not ready for a new city.”

This change in tone began to emerge as early as 1992, in a painting of a flat-roofed, utilitarian, warehouse-like building of the type that has become a symbol for Ruscha of some essential Southern California. The side of the building is painted with a single word, as if to sum up Ruscha’s growing exhaustion with the banality of a cityscape that once excited him and helped propel his remarkable body of work. That word is “Tires.” Points for honesty.

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

ALSO

Inuit throat singer Tanya Tagaq joins feminist performance series at the Broad on Saturday

What a Holocaust survivor has to say to South L.A. school kids — and how she uses art to connect

Hammer Museum's 'Radical Women' to showcase Latina artists on the politics of the female body

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.