Mastering old techniques and new technologies to re-create the moon landing for ‘First Man’

A close-up, behind-the-scenes look at how the moon was digitally re-created for the climatic landing scene of the Neil Armstrong biopic “First Man.”

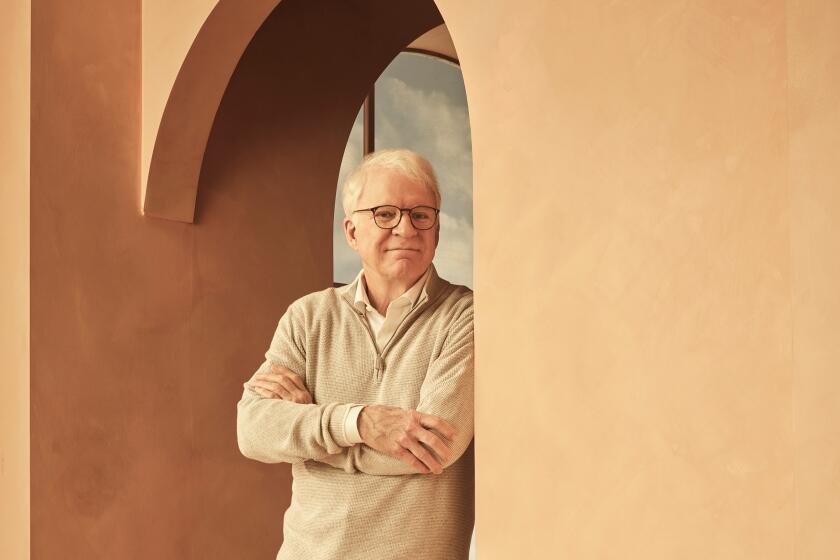

In camera. In camera. In camera. For production designer Nathan Crowley, the “First Man” creative brief couldn’t have been more emphatic when director Damien Chazelle laid out his approach to filming NASA’s 1960s-era space program. Crowley, who earned four Oscar nominations as Christopher Nolan’s go-to designer on such movies as “Interstellar” and “Dunkirk,” eagerly embraced the analog aesthetic. “Over the years,” he says, “I’ve become much more interested in creating environments using physical tools, physical sets, physical techniques rather than just popping in a green screen and CGI’ing everything.”

The movie’s bone-rattling opening sequence, which re-creates Neil Armstrong’s 1961 X-15 test flight, exemplifies Crowley’s full-immersion design aesthetic. “I went to Edwards Air Force Base in the California desert to see where the event actually happened,” says Crowley, speaking by phone from his home in New York. “They had this X-15 mock-up on a pedestal and it suddenly became obvious to me: ‘This is not a plane. It’s a ballistic missile with a cockpit on one end.’ The top of the canopy holds the pilot’s head in position because otherwise his neck would break.”

Ryan Gosling, portraying Armstrong, sat inside Crowley and company’s replica X-15, which was shaken on a soundstage gimbal. Rear-projection footage displayed panoramic vistas of the stratosphere while an 80% scale B-52 bomber hovered outside the window. “By moving the camera into this restricted physical environment, it allows people in the audience to realize, ‘This is terrifying.’”

The Gemini 8 capsule, launched in 1966, also impressed Crowley with its modesty of scale when he studied NASA manuals and visited Kennedy Space Center in Florida. “Re-creating the interior with all its working elements, we wanted it to feel like you’re going into a coffin when the door locks and you hear these old bolts and steel and clanking and creaking,” Crowley explains. “People often look at these missions in a kind of glossy way but the reality was quite the opposite. It was sweat and grit and bolts and dirt.”

To fabricate the miniature and full-size spacecraft replicas featured in “First Man,” 16 3-D printers housed in an Atlanta soundstage operated around the clock producing pieces. Artisans then used traditional Hollywood skills to finish the surfaces, old-school style. “Imagine building a set with a bunch of plywood,” Crowley says. “This was basically the same process except instead of carpenters we had mold makers. We used great scenic painters, plasterers, metal guys adding little bits. I hired Ian Hunter, who ran the last miniatures shop in the U.S., and he applied every little trick in the book. Producing the miniatures alongside the full-scale pieces was super useful because we needed both versions to look exactly the same.”

While craftspeople produced everything from the topsy-turvy “multi-axis spinner” to the meticulously detailed mission control headquarters, Crowley postponed his most daunting design challenge: the Apollo 11 moon landing site. “As a designer,” he says, “I’ve learned that sometimes you have to let things tick in your mind a while until an answer presents itself. All of a sudden a door opens up and lets you in.”

In “First Man,” the door to a real-looking moonscape was opened by an Atlanta location manager, who alerted the British designer to a quarry outside the city. “The locals took away all their machinery,” Crowley recalls. “We banked the whole background up to kill the trees and created this site of gray nothingness. Then we sculpted the moon.” Dusting the surface with gray-dyed C90 paper bits normally used as fake snow in movies, filmmakers mimicked Apollo 11’s Tranquility Base made iconic during the 1969 televised landing. Crowley says, “Our greens department spent two weeks putting in all those little potholes and craters and rocks in the right place. I didn’t want anyone in the audience to question it: We’ve landed on the moon!”

By the time production wrapped, Crowley had satisfied the “in camera” mandate for nearly every frame of the movie. “I felt like we’d gotten back to the old techniques I loved so much when I first started out,” he says. “I remember working on ‘Bram Stoker’s Dracula’ where we worked with old techniques like rear-screen projection. We do that in ‘First Man’ too, except now rear projection uses LED lights, which have a brightness and luminosity that allows the camera to read everything beautifully. On ‘First Man,’ it’s all about old techniques and new technologies, which is bizarre.”

FULL COVERAGE: Get the latest on awards season from The Envelope »

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.