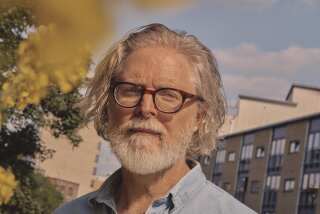

Q&A: ‘Widows’ director Steve McQueen discusses audience reactions: ‘I love hearing the gasps’

Steve McQueen isn’t used to moviegoers telling him they want to see his films again. Though uniformly excellent, McQueen’s movies are raw, unsettling and often brutal examinations of history and the human condition. One viewing is usually enough for these demanding endurance tests.

“Certainly, that was the case for ‘Hunger,’” McQueen says of his 2008 debut about a prison hunger strike. “‘12 Years a Slave’ too, for obvious reasons. Maybe ‘Shame’ was something of an exception. The dog whistles go off in the room for that.”

But now, with the layered heist-thriller “Widows,” McQueen has made a film that, although not a full-blown crowd-pleaser — it’s a bit too shrewd and stylish to fall under that umbrella — has been roping people in for repeat viewings. A remake of a 1983 British limited series that hooked McQueen when he was 13, “Widows” follows a group of women, led by Viola Davis, carrying out a robbery that their husbands planned but never completed. (The film’s title betrays the reason why.)

McQueen, working from a screenplay he co-wrote with Gillian Flynn (“Gone Girl”), moved the action to Chicago, weaving in commentary on income inequity, toxic masculinity and a broken political system. We spoke recently about his personal connection to the film.

ON WRITING: With politics, gender and race at its core, ‘Widows’ packs in much more than a heist »

Why did you connect with “Widows” so deeply when you were 13?

It was a hard time for black children growing up in the ’80s, dealing with what people perceived you were capable of. You were judged on your appearance. And I saw this program with these women being judged and going on a journey and tilting these stereotypes on their head. It was thrilling.

Do you remember clearly identifying with the women?

What happens with black people is that you get politicized much earlier. Definitely in the UK, and also in the United States, depending on where you grow up. You start asking questions at a young age.

What was it like then to return to this story and these women that you’ve held so close for 35 years?

Bittersweet. I’ve returned to the story, and nothing’s changed — other than maybe the conversation that just started with #MeToo. I suppose that’s something. If this picture can help advance the conversation, then great. That was never my intention, however.

What was your intention?

My intention was to make a picture where the answer to a lot of things is within us all. What I mean is that you have these four women from different social and racial backgrounds and they form a team and they accomplish a goal. It’s very American, this story. That’s why I love America. You’ve got people from all parts of the world who come together to make this great country.

I remember rainy days in London, I would open this book, “Made in the U.S.A.,” and dream of America. America was a mecca of freedom and possibilities. And that’s the foundation of this picture. The women forget their differences and accomplish something.

You have a long history with Chicago, going back to your first museum show at the Museum of Contemporary Art. What were your first impressions of the city?

It was 1996, and my girlfriend, who is now my wife, went to the Democratic convention when Bill Clinton was president. And, yes, that was my first museum show. So I always say my first footprint in Chicago was art and politics.

The racial divisions in the city were obvious. People looked at my wife [writer Bianca Stigter, who is white] and I in a very mistrustful manner. I remember walking across a bridge with my wife and some guy knocked into her really hard. I was fuming. Very odd. Yeah, I remember that.

What more did you learn about Chicago making “Widows”?

I didn’t know the geography and the close proximity between wealth and some of the poorest parts of America. Doing research, I’d travel from an amazing apartment, looking at this man’s collection of Olympic torches, to talking to a woman who was losing the house where she had lived for 50 years because she couldn’t pay the interest on her mortgage. It was heartbreaking. It messed with my head, for sure.

Was that the genesis of that three-minute shot in the film where Colin Farrell’s politician is being chauffeured home and we see the neighborhoods changing through the car window?

It wasn’t planned. We saw the neighborhoods were close and we said, “OK. Let’s do it like that.” You adapt to the location and you discover. And because we’re not seeing Colin in that shot, you lean in. You listen more. It’s like great radio. What we see through the car windows gives us a great deal of information about the divisions of this city. They are enormous.

I’ve seen the movie twice, and on both occasions the audience audibly gasped multiple times. Have you heard the gasps?

I love the gasps. It’s very satisfying. It’s why I love cinema. I’m not making a picture for someone at home with a laptop. Going to the cinema is a shared, participatory activity.

What movies have made you gasp?

I saw “North by Northwest” on one of my first dates with my wife. People stood at the end and applauded. It was incredible. And then “Beau Travail” by Claire Denis. You couldn’t find two more different movies. One is a suspense-thriller, the other, Claire Denis, an art house … well, people call it that. I don’t have that distinction. I have good movies and bad movies. That’s it.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.