Commentary: ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ is a perfect mirror of modern times. Do we really need a sequel?

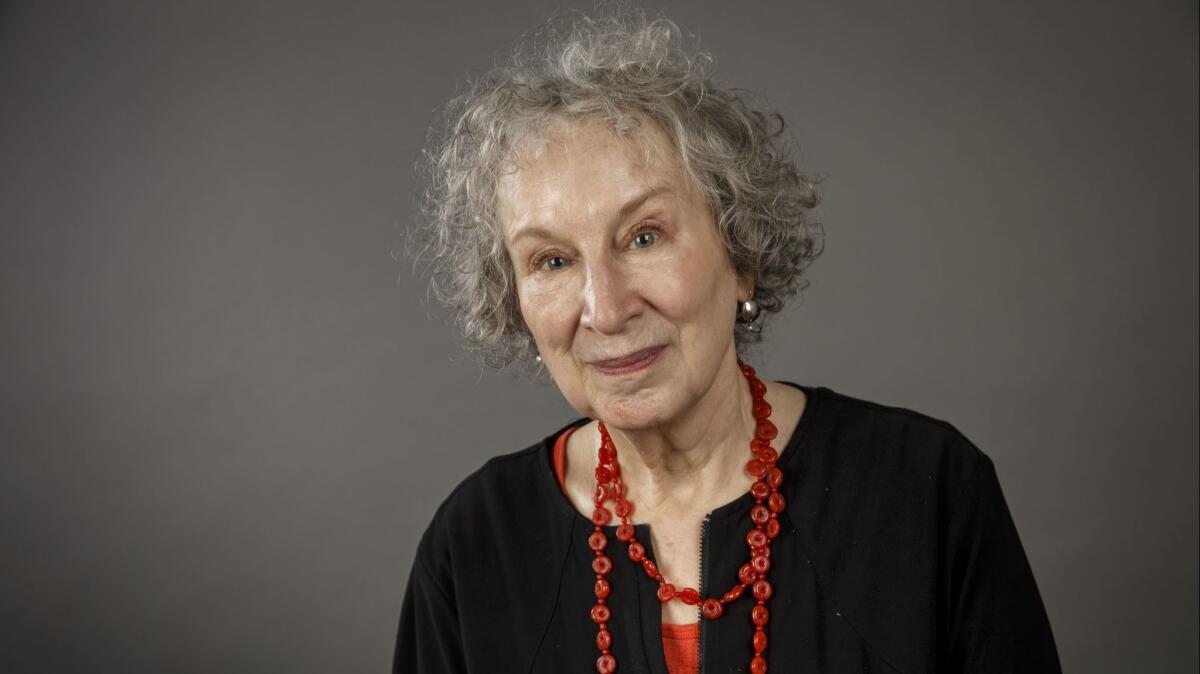

More than 30 years have passed since Margaret Atwood published “The Handmaid’s Tale,” a wrenching story of living under a patriarchal fundamentalist regime where fertility is prized and women are subjugated.

With a wildly successful adaptation airing on Hulu and women dressed as handmaids haunting anywhere their reproductive rights are at risk, Atwood’s novel is more relevant than it has ever been. Just this week it’s been fodder for memes involving White House holiday decorations.

So in this age of reboots and remakes, it should have come as no surprise when the author announced Wednesday that a sequel is in the works.

The original “Handmaid’s Tale” spun a story about an enslaved woman called Offred — literally a slave “of Fred” — and her experiences while living in Gilead. With a cliffhanger ending, the novel left many unanswered questions about both the republic and Offred’s fate.

Atwood has already said that the sequel, “The Testaments,” will go a long way toward clearing up fans’ questions, while also drawing inspiration from the current cultural climate.

But why?

Wednesday’s announcement felt like the recent trend in pop culture toward leaving no stone unturned.

Just look at “Harry Potter” mastermind J.K. Rowling’s Twitter feed. Despite writing more than a million words in the seven books that make up the greater “Harry Potter” series, Rowling keeps adding things to the official canon that were only hinted at or, worse, were never suggested at all in the texts.

The most famous example remains Rowling’s declaration — just months after publication of the final book in the series, “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows” — that she always intended for Hogwarts headmaster Albus Dumbledore to be gay. Which is a fine revelation for a series that had a shocking lack of inclusive representation, but seems like cold comfort when you realize she could have just included that information in the text itself, as opposed to tacking it on after the fact.

Atwood’s announcement on Wednesday alluded to addressing lingering questions, but any more information about the inner workings of Gilead seems destined to detract from, not enhance, the original text.

Even more concerning, perhaps, is Atwood’s statement that the new book is inspired by the world as we now know it. The power of “The Handmaid’s Tale” comes in part from it being a missive from the past. As incisive as it surely seemed in 1985, it reads to modern audiences like a warning, a flare to keep our guard up and watch for the signs.

It also imparts, strangely, a message of hope: We can get through this. We can dismantle the power structures that chain us. And we can do it together.

I don’t want a new version of “The Handmaid’s Tale” about right now because right now is already hard enough to endure. There’s no insight to be gleaned from writing about modern-day America, because that’s what Atwood’s prescient novel did in 1985.

Many already filter our world through the lens of Atwood’s Gilead, so if and when the author reframes the republic within current circumstances, it will create a dystopian ouroboros for the ages.

Atwood is a brilliant writer who deserves every benefit of the doubt. If anyone is deft enough to avoid the pitfalls of a late-breaking sequel a la Harper Lee’s “Go Set a Watchman,” it’s her.

But it’s unnecessary. Atwood already wrote the perfect handbook for our troubled times. Asking for any more feels like tempting fate.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.