The black hair revolution is happening now on a screen near you

If your hair is relaxed, white people are relaxed. If your hair is nappy, they’re not happy.

— Paul Mooney, “Good Hair”

On a late summer day in a Hollywood photo studio, actress Sanaa Lathan sat patiently in front of a vanity mirror and countertop filled with brushes, bottles and containers of hair and makeup products.

She was surrounded by a beauty team she trusted, celebrity hairstylist Larry Sims and makeup artist Saisha Beecham, who fluttered around her, blow-drying her short, defined curls and touching up her eyeliner and mascara, all while she answered questions about her recently released Netflix film, “Nappily Ever After,” over the hair dryer’s constant hum.

It was a fitting setting. The film, about an ad executive who suffers a crushing heartbreak, uses hair as a vehicle to examine the particular struggles black women face.

While shooting the film, Lathan’s hair journey mirrored Violet’s, the character she plays. She dyed her hair, used a variety of wigs and in the film’s most memorable scene, took a razor to her blond hair, shaving it down to the scalp. Lathan said the scene was real — she opted to shave her own hair instead of using a bald cap.

“Once I did the reveal, I was just surprised about the response,” Lathan said. “It was almost like people were saying I look better with it.”

In one big way, however, Lathan’s hair journey was different from the character she plays in the Netflix feature. Her mom encouraged her to embrace her natural hair from a young age. “My mother was really good about instilling in me that it’s beautiful,” the actress said.

Even so, she added, “[My mom] has very thick, curly hair, more toward the European side of texture, and I remember wishing my whole childhood that I had that — OWW!”

Almost as if the hair gods were putting in their two cents, the commotion — the styling, the makeup, the interview — became too much as the heat of the blow dryer got a little too close to her skin. “OW!”

Although temporarily overwhelmed, Lathan took a breath and kept talking. After all, she knew she was with beauty pros who understood how to skillfully work with her hair texture and skin color to make her pop on camera. As a black actress who made a name for herself in “Love and Basketball,” “The Best Man” and other romantic comedies in the late 1990s and early 2000s, she hasn’t always had access to hair stylists who could showcase her natural hair — or producers who would even want that look.

Lathan’s not alone. Black actresses, whether by choice or under pressure from Hollywood, have altered their natural hair to appeal to mainstream audiences since their first appearances in film and television — from Josephine Baker’s plastered-down coif in 1934’s “Zouzou” and Hattie McDaniel’s mammy roles in “Gone With the Wind” and beyond in which a tied-up scarf often hid her hair.

But lately, as more black filmmakers and showrunners gain creative control, there has been an emergence of projects that showcase the diversity of black life — and hair styles. This year’s Marvel blockbuster “Black Panther” was the best showcase yet of the variety of black hairstyles. And recent TV shows, including “Black-ish,” “Insecure,” “She’s Gotta Have It,” “Dear White People” and “Queen Sugar,” regularly show off and talk about issues around the many ways black women wear their hair.

The complex politics of hair

“We have organized around this Eurocentric standard of beauty almost exclusively until very recently,” said culture critic and former Essence fashion and culture editor Michaela Angela Davis. “This idea of trying to conform to a standard that makes white people feel comfortable, that’s really what it is. The idea of black hair’s inability to lay down is a metaphor for our resistance and it has been a point of contention.”

Understanding the struggle of black women’s hair on screen is also understanding that black women’s hair — which can range from loose waves to tightly packed coils — goes much deeper than a style. It’s tangled up in painful history, politics, race and gender.

During slavery, white owners used markers including skin color and hair texture to create an arbitrary hierarchy among slaves. Those with more European features, such as lighter skin and loose, wavy textured hair, had a higher status than others with distinctively sub-Saharan African features.

Even after slavery, black people with lighter skin and looser curl patterns were often able to achieve a higher status in society. Tools that helped black women straighten their hair, such as chemical relaxers and heat, also helped some women better assimilate into their communities.

Eurocentric beauty preferences also extended to the silver screen. From the 1930s through much of the 1960s, if black women weren’t playing slaves or servants, they were often brought on as featured performers wearing hairstyles consistent with white nightclub singers. Even Lena Horne and Dorothy Dandridge, who earned starring roles in some of Hollywood’s rare black musicals (“Cabin in the Sky” and “Stormy Weather” for Horne, “Carmen Jones” for Dandridge), wore hair that imitated popular white styles of the time.

In 1966, Nichelle Nichols, as “Star Trek’s” Lt. Uhura, became one of the first black actresses to be a regular cast member in a network show playing a role that was neither servant nor singer. Two years later, Diahann Carroll made history as the star of “Julia,” the first network show centered around a black woman who wasn’t a servant. Although Nichols’ and Caroll’s signature hairstyles evolved over the course of their shows, they were introduced to their TV audiences in the elevated, hairspray-heavy coif known as the bouffant.

The civil rights movement led to freedom in personal style, as black people began reclaiming their natural hair. That black pride also extended into Hollywood, leading to the Blaxploitation film era that prominently featured actresses such as Pam Grier wearing spectacular afros in films including “Coffy” and “Foxy Brown.”

“With the black power ethos came a different way of looking on screen,” said Christine Acham, a cinematic arts associate professor at USC. “There was a more natural look and a less traditional Hollywood look. There was a lot of movement around Angela Davis’ image on her FBI poster, and we could see it translate over to film.”

Diana Ross appeared in an afro and gold hoop earrings on the cover of her 1971 solo album “Surrender.” And as the star of the 1975 Berry Gordy film “Mahogany,” she goes through a range of white and black hairstyles as she chooses between the cruel world of high fashion and her community activist true love played by Billy Dee Williams.

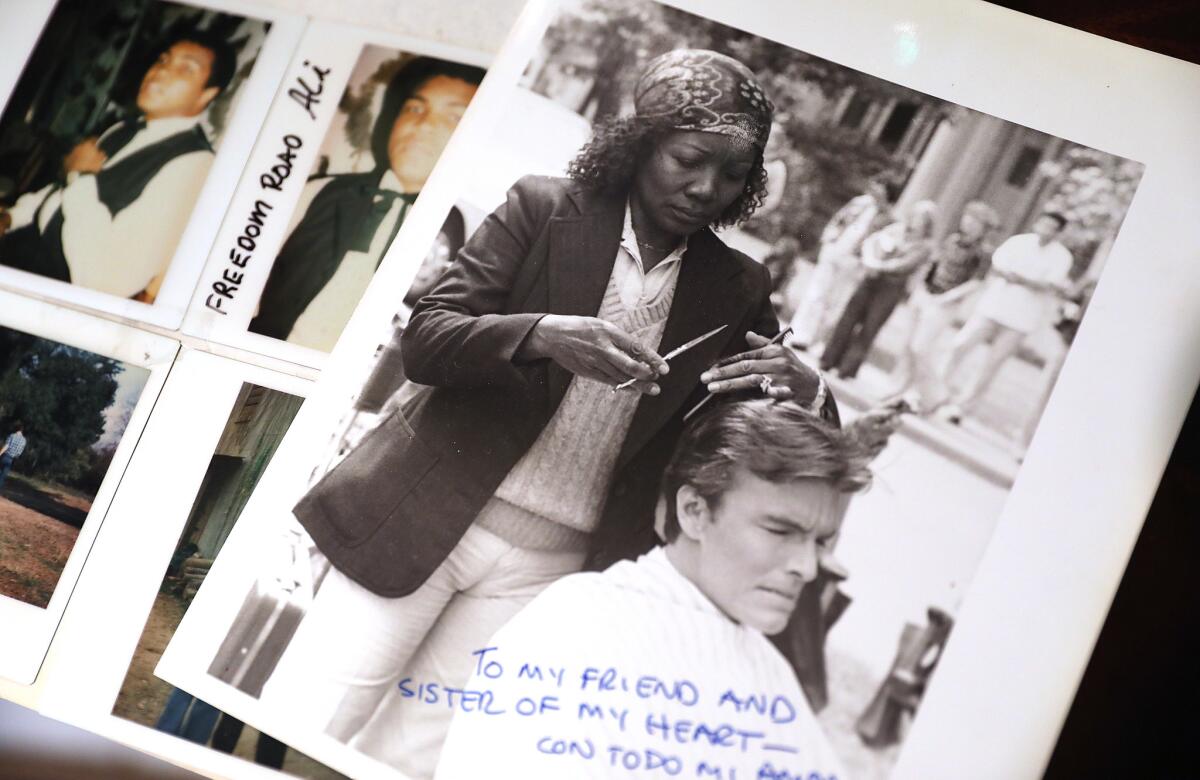

Spike Lee’s 1988 film “School Daze” offered up a sharp critique of divisions between dark and fair-skinned members of the black community — including the musical number “Good and Bad Hair.” And Whoopi Goldberg wore locs in “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” and many other films, while rappers Salt N Pepa inspired girls all over the country to imitate their asymmetrical haircuts — an accidental style of necessity that was improvised when Pepa burned her hair during a perm. Overall, however, the 1980s and 1990s saw a return to a more Eurocentric standard of beauty for black women on screen.

Felicia Leatherwood, widely known for encouraging celebrities to embrace their natural hair, is the hairstylist behind Issa Rae’s natural hairstyles on HBO’s “Insecure.” But growing up with kinky-coily textured hair, Leatherwood said she didn’t often see herself reflected on TV and film.

“We had ‘Diff’rent Strokes’ back then and ‘Facts of Life’… Some of the mothers that were older had afros, which meant that when you thought of an afro, you pretty much thought of an older woman who achieved everything she wanted in life,” Leatherwood said. “But you didn’t have young women that inspired you to wear your hair natural when I was young.”

Several actresses recalled their own experiences auditioning for film and television roles in the 1990s and early 2000s, with constant requests for long, straight hair.

"When we were coming up, we couldn’t wear our hair natural," Lathan said. "It was just around the time that weaves were coming in, or you’d be going up against somebody who was maybe biracial and would have long hair. I literally got the feedback many, many times, can she look more like this girl who has hair down to here."

Erika Alexander, who played Maxine Shaw on the 1990s series “Living Single,” said she was encouraged to keep a natural look when she got her start in theater.

"When I started showbiz, there were no [black] ingenues. I wasn’t looked at as pretty or elegant," Alexander said. "I was hired to look 'foster care' or a slave."

The meaning of ‘Good Hair’

After being asked by his young daughter, “Daddy, how come I don’t have good hair,” comedian Chris Rock was inspired to make a documentary exploring black women’s desire for straight hair. Premiering at the Sundance Film Festival in 2009, “Good Hair” — named after the dated and loaded term that has been used to describe black hair that resembles white hair textures — featured interviews with black actresses including Nia Long and Raven-Symoné and took a critical look at the multi-billion dollar black hair industry, which often pushes weaves and chemical straighteners.

“If you’re not seeing yourself reflected,” Lathan said, “if you’re only seeing something that’s not you...what does that do to your self worth?”

In the last few years, particularly on TV, hair has become a kind of shorthand way of portraying what it means to be a black woman. In a crucial scene on a 2014 episode of “How to Get Away with Murder,” stoic defense attorney Annalise Keating, played by Viola Davis, strips off her short, straight wig to reveal her kinky-textured natural hair. In the “black-ish” spinoff “Grown-ish” on Freeform, Yara Shahidi’s character, Zoey Johnson, is shown keeping her hair wrapped in scarves at night.

“Television is leading the way with ‘Insecure,’ ” writer Michaela Angela Davis said. “Molly with her weaves and corporate look, Issa with natural hairstyles...and bougie Amanda headpieces and blonde — the cast of ‘Insecure’ has every kind of hair personality in there.”

Hollywood standouts — among them Viola Davis forgoing her wig for a cropped afro at the 2012 Oscars, the rise of Lupita Nyong’o who sports short kinky-textured hair and director Ava DuVernay’s long locs — show that the industry is slowly catching up to the natural hair movement, which began picking up steam in the early 2000s.

“In the last couple of years, I feel like there’s been a real revolution,” said “black-ish” star Tracee Ellis Ross. “This is what I’m going to choose for myself — to be who I am and wear my hair as I choose, when I choose — whether that is a wig, a weave or my natural texture, or braids or whatever it is.”

But even in recent years, Lathan has worked on sets where hairstylists didn’t know how to work with black hair. One foolproof method to ensure her hair remains healthy is to just do it herself, including bringing her own wigs, to make sure she can feel confident on screen.

“Every hairstylist says, ‘I know how to do black hair.’ My test is, ‘Do you know how to use a stove?’ ” Lathan said, laughing. “And usually, they’ll say no.”

“Everybody has a story of going on set and having someone go, ‘Uh, well let me just curl it with a curling iron,’ and these women are wearing hair natural,” said Simone Missick, who plays Misty Knight on Netflix’s “Luke Cage.” “There's this community for actors, we all share our stories and experiences and share tips to help everyone keep themselves from going bald.”

“If I don’t believe your hair, I don’t believe you,” Michaela Angela Davis said. “You remove this ability for her to be complete or honest as this black, modern girl if her hair is whack.”

Believability and representation in popular culture has lasting effects. Both Alexander and Lathan recalled their childhoods when they dreamed of having long, straight hair. “We got our hair washed, and the towels, and acted like that was our long, beautiful hair,” Alexander said. “For that time, you felt normal.”

“Nappily Ever After’s” producer Tracey Bing, who went to predominantly white schools and was never happy with her hair as a child, said, “I never had a doll that looked like me. And I wonder how my image of myself would’ve changed if I did.”

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.