David Fincher and Martin Scorsese on why Hitchcock was more than the Master of Suspense

Director David Fincher was 7 when he saw the film book “Hitchcock/Truffaut” on his father’s desk. He promptly picked it up and started to flip through the pages.

Though Fincher had already decided at that tender age that he wanted to be a filmmaker — “the die had already been cast,” he recalls — reading “Hitchcock/Truffaut” was “part of my cinematic home schooling. I had never thought about kind of the matrix of film language before.”

In 1962, Alfred Hitchcock, who had been directing films for nearly 40 years, met with the former Cahiers du Cinéma critic-turned New Wave director Francois Truffaut (“The 400 Blows,” “Jules and Jim”) in Los Angeles for a week of conversations about filmmaking.

François Truffaut was on a mission to make American critics and audiences realize Hitch was a true auteur and not just an entertaining filmmaker. Truffaut achieved his goal when the book was published in 1967. Critics, filmmakers and fans have come to regard Hitchcock in a different light because of the book, which has become one of the most influential in cinema history.

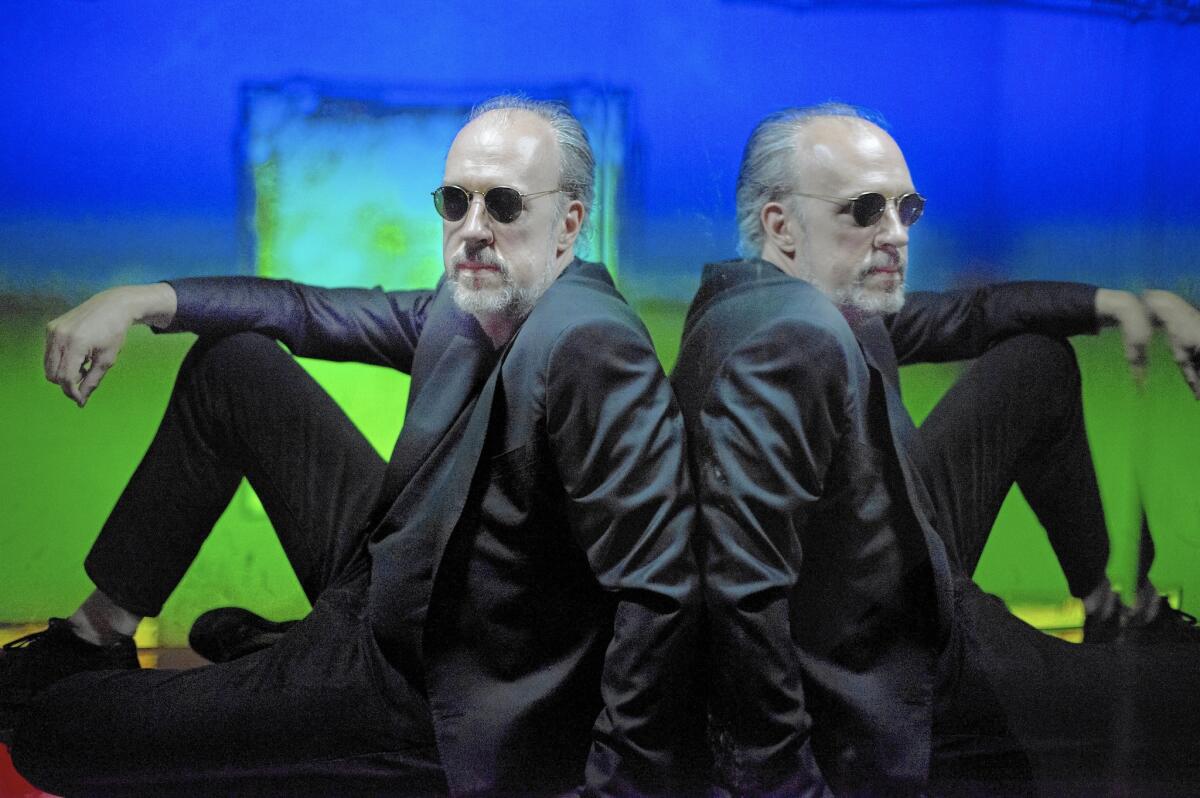

Kent Jones’ documentary, “Hitchcock/Truffaut,” which opens Friday, uses pictures and audio tapes from that groundbreaking week of interviews, numerous clips from Hitchcock’s classic films, and interviews with several of today’s leading filmmakers, including Fincher, Martin Scorsese, Wes Anderson, Richard Linklater and Arnaud Desplechin.

Before “Hitchcock/Truffaut,” “there was still an idea of filmmaking as kind of a closed world, like Xanadu in ‘Citizen Kane’: ‘No trespassing,’” writes Scorsese in an email. “We’d had all of those films from Europe and Asia and auteurism and so on, but there was still this lingering feeling of ... how dare we make movies? Where do we get off?”

With the publication of the book nearly 50 years ago, Scorsese notes, “you suddenly had two filmmakers from two different generations and two different cultures speaking not about old Hollywood and what it was like to work with this or that movie star and the food at the Brown Derby, but about the art of cinema, on a nuts and bolts level, proudly. So it gave us a richer sense of our own art form.”

Fincher says that the Cahiers du Cinéma vision of Hitchcock “precisely redefined him as something more than the Master of Suspense. I think there is no doubt Hitchcock was flattered by the reassessment.”

In the audio tapes, Hitchcock, who became lifelong friends with Truffaut, is open and often playful with the young director.

The reason is simple, according to Scorsese: Hitchcock was talking to a fellow filmmaker, not a critic.

“Add it doesn’t matter that the filmmaker happened to have been a former critic himself,” he says. “The point is Truffaut knew what Hitchcock was talking about. They had a common language. It’s not the same with a critic or a historian. Also in this case, you have the young filmmaker coming to the older one and saying, ‘You’re my master, you’re my guide, and I want people to know how important you are to me, to all filmmakers, to the art of cinema.’ Of course he was open.”

Fincher describes Hitchcock’s 1958 romantic psychological thriller “Vertigo,” starring Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak, as something “odd, perverse and almost poetic.” But truth be told, Fincher doesn’t like the film.

“But I think it’s insanely interesting. I think the best Hitchcock is when Hitch is peeping like in ‘Psycho’ and ‘Rear Window.’ I think he was his best at his most honest.”

Scorsese disagrees. “I think ‘Vertigo’ is one of the greatest films ever made,” he says. “I saw it on its first run in VistaVision. It was perplexing at first, but I liked it and couldn’t say why. It was quite different from what people expected of Hitchcock, and the story was so odd, so purely emotional.”

Still, Scorsese doesn’t take “Vertigo” seriously as a realistic story. “I never care about where I am in the picture. These are probably the things that bother Fincher; I get lost in the story, in the atmosphere and the images, just like Stewart does. I look forward to that each time I see the film,” he says.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.