‘Ten Thousand Saints’ recalls violent clash of cultures in 1988 New York

From left, From the movie “Ten Thousand Saints,” Emile Hirsch, Ethan Hawke, Hailee Steinfeld, filmmakers Shari Springer Berman & Robert Pulcinion and Avan Jogia at the L.A. Times photo & video studio at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival.

Shari Springer Berman was walking down a street here one sweltering summer night in 1988 when a sight took her aback: Out of nowhere, a passerby was being clubbed by a policeman.

“The man had just walked out of a bar and was doing nothing wrong,” she recalled. “And this cop just came up and hit him and knocked him to the ground. You could tell the cop knew what he was up to because he was covering his badge.”

The night was Aug. 6, and what Springer Berman was witnessing were the tendrils of the Tompkins Square Park Riot, which had stretched west from the riot’s locus in the city’s East Village neighborhood.

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter >>

Though hardly a political sort, Springer Berman soon walked over and joined in the protests, part of a boiling class war between the neighborhood’s eclectic residents and homeless on the one hand and a zealous police force, backed by a new monied class, on the other. More than 100 complaints of police brutality were later lodged, with some such incidents captured on videotape for the first time.

More than a quarter of a century later, Springer Berman, 51, still remembers those days vividly. And she felt sufficiently strongly about them to adapt, along with husband and filmmaking partner Robert Pulcini, a novel of that tempestuous period by Eleanor Henderson titled “Ten Thousand Saints.” The movie arrives in theaters and on-demand Friday with a kind of eerie timeliness, amid more allegations of police misconduct in Ferguson, Mo., and on the same weekend as “Straight Outta Compton,” which contains similar cop-community echoes.

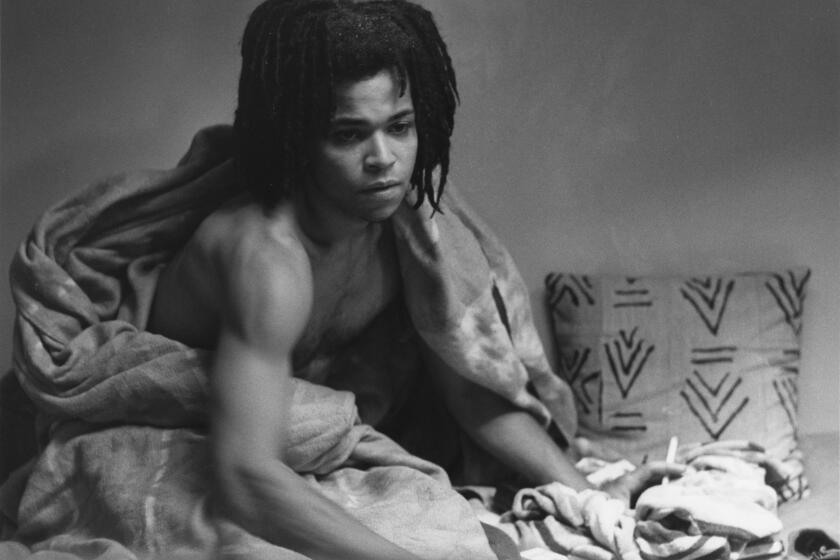

“Saints” tells the story of Jude (Asa Butterfield), a Vermont teenager who moves in with his estranged father Les (Ethan Hawke) in the East Village after pal Teddy dies of a drug overdose. Jude soon finds an alternate community anchored by Teddy’s straight-edged rocker brother Johnny (Emile Hirsch). Though it follows a set of interconnected personal stories, the film’s potent backdrop is a downtown metropolis in turmoil, with events building to a climactic scene at the Tompkins Square Riot.

The year 1988 was part of a transitional period in New York and big cities generally, and the neighborhood Jude arrives in is suspended between the crime and artistic ferment of an earlier era and the gentrified culture that would follow.

“You sound like all the yuppies who want to get the homeless out of here and make it look pretty,” Les tells Jude when the latter complains of Tompkins Square’s unruliness.

“Like that’s going to happen,” Jude says.

“Don’t be so sure, champ,” Les replies. “Money’s got a big mouth.”

As Springer Berman and Pulcini walked around the park last week, the utterances from that mouth are evident, even in the basic surroundings.

Much of the fencing in the park has gone from chain link to the more genteel iron bars. Flowers have been planted. A summer-camp group wanders through. Several men in suits hurry from or to a corporate job. Even the skateboarders seem as likely to have designed a million-dollar app as they are to have come from a punk show. Few seem aware of the riot’s anniversary.

All of this, needless to say, made shooting difficult for the “Saints” crew. The tops of buildings hadn’t changed, and there are still street signs and a few landmarks that have not been turned into a Chipotle or a gourmet frozen yogurt shop. But they are becoming fewer and farther between. Even graffiti had become a scarce commodity — which led to some creative solutions.

“If we saw a graffiti-covered truck, we’d flag it down and give them 50 bucks to park in front of a Citi bike stand,” Pulcini said.

The filmmakers did make use of one natural resource that always seems to be in abundance in the city. “I would often see our production designer picking up garbage,” Pulcini said. “I’m not going to pay for garbage in New York,” Springer Berman added.

“Saints” looks to capture both the beauty and messiness of the past, to walk up against a line of romanticization while being careful not to cross it. “I get irritated sometimes when people say how difficult it is in New York now and how much better it was then,” Pulcini said. “Yes, it’s hard because it’s expensive and you’re living with 13 roommates if you’re in your 20s. But back then you were mugged and pulled into a stairway at gunpoint. There was a rat in every apartment. I don’t know that it was easier.”

The film is interested in flipping other narratives. Most movies about youthful rebellion concern a breakout from repressive parents to a place of moral permissiveness, often through drugs. But Jude’s family life is chaotic, while the musicians he hangs out with are serious, stone-cold-sober types.

Though about class more than race, the riot came in the tradition of, and was an early harbinger for, the fractious relationships between citizens and the police currently seizing the headlines. As a riot scene was being filmed, a protest was going on in nearby Union Square, and police asked them to shut down temporarily lest any of the protesters think the riot was real and join in.

Springer Berman and Pulcini have been making films for two decades. After getting their start in documentaries, they broke out with the 2003 graphic-novel tale “American Splendor” and would later be known for a number of features, including the 2011 HBO movie “Cinema Verite” Their connection to their current source material is strong: Pulcini, 50 and with a low-key energy, was born in Queens but moved away to Ohio when he was a boy, returning after college. Springer Berman, more outspoken, was raised in Brooklyn and partook of the bohemian scene portrayed in the film.

The couple now lives on the upper-middle class Upper West Side and have become attuned, especially after making the movie, to the ways many American cities have changed.

“There was a time when you would have to put a ‘No Radio’ sign in your car,” Springer Berman recalled. “And the other day we were going to dinner and we left our iPad in the car. We were going to go back for it and then we realized, nah, it’s fine.”

As they were seeking permits to shoot the riot, there was resistance to their rebuilding the tent city from wealthy residents who live near the park — an irony possibly lost on the city approval agencies.

As they stood in the park, not all of the traces of the old New York had washed away. There were some colorful characters, including a scruffy-looking couple with a boom box, and a middle-aged man in a “Castaway” beard who rode by on a bike with charcoal strapped to the back, en route to a barbecue of unknown provenance.

“Gentrification isn’t a good or bad thing on its own,” Pulcini said, “and a city that goes through it isn’t better or worse. It’s just reborn as something else.”

MORE:

Regina Hall’s well-ordered life as an actor, not a nun

Uggie dies: ‘The Artist’ dog had that intangible star quality

Cinespia’s John Wyatt celebrates cinema with screenings at Hollywood Forever

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.