Celebrities quick to apologize for mistakes but are they sorry?

“Sorry seems to be the hardest word,” Elton John once sang, but for celebrities that no longer appears to be the case.

Apologies from high-profile musicians and actors have been piling up recently, reflecting regret (or at least its image) for a wide variety of perceived offenses, from the seriously damaging to the laughably slight.

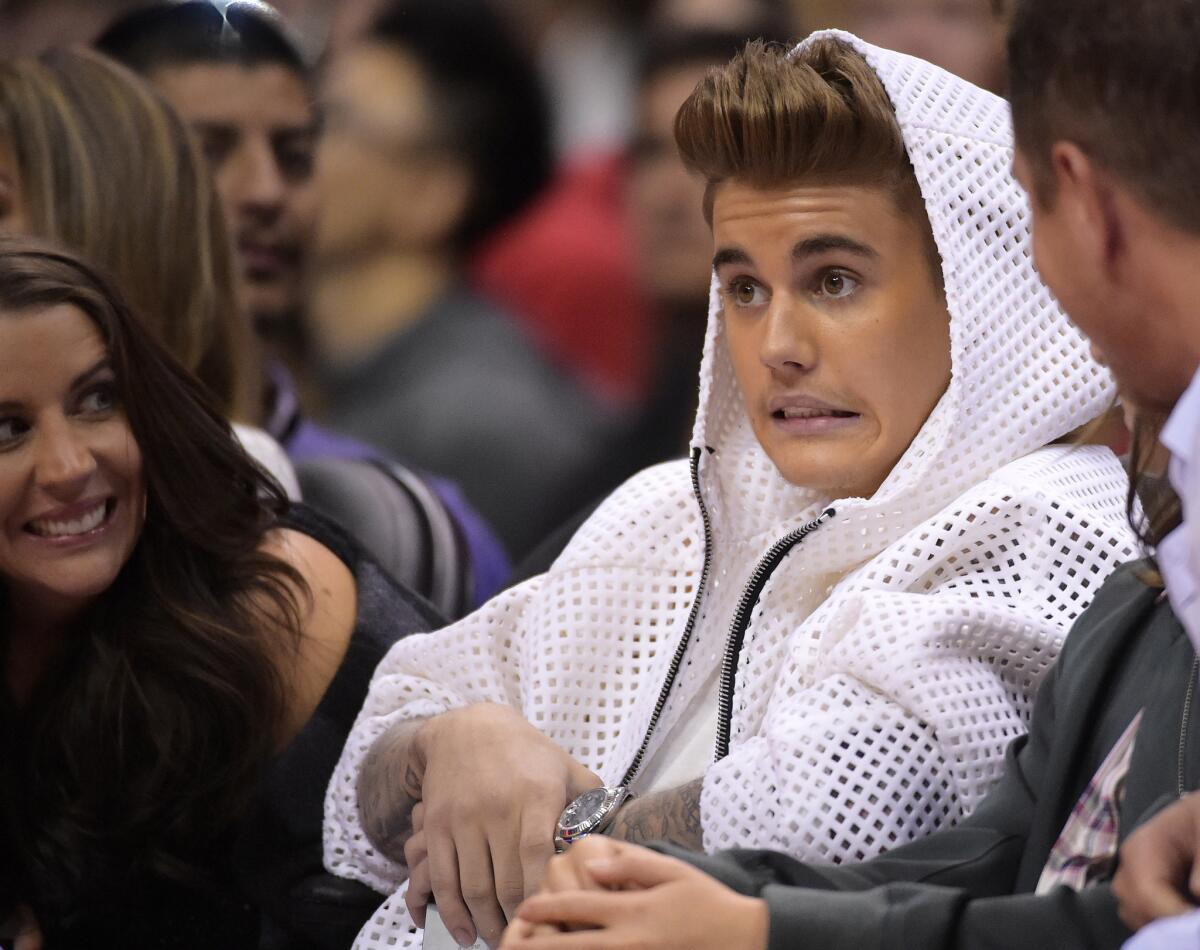

There was Justin Bieber seeking atonement after videos surfaced in which he made racist remarks. There was Jack White downplaying disparaging comments he’d made about the Black Keys. And there was Jonah Hill apologizing for using a homophobic slur in a confrontation with a photographer.

The show-biz mea culpa — it’s nothing new, of course. Think of John Lennon walking back his claim in 1966 that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus.

But thanks to an online news cycle that demands a constant churn of fresh information, the nature of these apologies has fundamentally changed — and not for the better.

Most noticeably, they’re arriving faster than ever. In 1995, after he was arrested in the company of a Hollywood prostitute, Hugh Grant waited two weeks to go on “The Tonight Show” — long enough that he told Jay Leno about having received letters of support from fellow celebrities. (Not emails, mind you — old-fashioned, takes-a-while-to-get-them letters.)

Compare that to the matter of hours Pharrell Williams took recently to issue an apology for wearing a Native American headdress on the cover of British Elle.

“I respect and honor every kind of race, background and culture,” the “Happy” singer wrote in quick response to criticism on Twitter that he’d appropriated the traditional garb with insensitivity. “I am genuinely sorry.”

That acceleration reflects the way social media have minimized the distance between stars and the public, a development that in many ways has fostered greater communication. But it can also deplete the intended weight of whatever’s being expressed.

How much remorse could Pharrell really have experienced in the time required to dash off a few words? Such instant reversals feel compulsory, like stock declarations sitting in an electronic filing cabinet until the moment they’re needed.

And because these declarations now appear in the same fashion — on the flattening wave of a Google News alert — they have the effect of equalizing the wrongdoing they’re meant to redress.

In an age when even the slightest provocation can summon the Internet’s inexhaustible outrage, that’s often just fine. White saying he’s sorry for claiming that the Black Keys ripped him off? We should see that next to Liam Payne’s recent apology on behalf of his One Direction bandmates, who’d been caught on video joking about marijuana while sharing a rolled-up cigarette of some kind. The shared context emphasizes the triviality of these supposed misdeeds.

But when the White story gets mixed up with the Bieber story — a legitimately disturbing series of videos that include Bieber, then 15, blithely changing the lyrics of one of his songs to include the N-word — it’s interfering with our ability to consider each offense on its own terms. Both become part of the same static.

What’s worse, the endless recirculation of these responses creates the appetite for more — not just apologies, per se, but some kind of recognition of our collective dismay over this or that celebrity snafu.

After Jay Z and his sister-in-law Solange reportedly were involved in a physical altercation in a hotel elevator in May — a fight that ignited the Internet after security-camera footage was leaked to the gossip website TMZ — people seemed unwilling, even unable, to let the matter die without some official account of what had happened and why.

“Solange, Jay Z and Beyoncé break their silence on hotel elevator incident,” a CNN headline read when the three performers finally — finally! — issued a statement.

“At the end of the day, families have problems and we’re no different,” they said. It was as though they owed us that explanation — that their earlier silence had been an act of hostility.

But why do we need these statements, so many of which say nothing of value?

Artists process their experiences — the good ones and maybe especially the bad — through their art; that’s often one of the reasons they became artists.

Yet we’re creating an environment in which we seem to want artists to be publicists, processing through the dry formality of a press release.

Do Bieber’s videos, which he’s said document a time when he “didn’t understand the power of certain words and how they can hurt,” require some explanation?

Absolutely. The same goes for Hill, who accepted Howard Stern’s and Jimmy Fallon’s recent invitations to come on their shows and grovel.

But talk has never been cheaper than it is right now, when a retweet costs nothing more than the second it takes you to scroll beyond it. What’s more meaningful — and certainly more interesting — is the artistic response: the new song or the next movie role or the eventual tell-all memoir.

Bieber, for one, has already shown that he’s capable of using his music to take up past transgressions. (And maybe to commit new ones: On Monday the 20-year-old posted a picture of himself in a recording studio with Chris Brown, the famously troublemaking R&B star.)

“I’ll acknowledge our trust has been broken,” Bieber sang on last year’s “Journals,” a surprisingly candid set of songs that followed several unsavory episodes in which he seemed to be making a willful break from his teen-idol origin.

And then there’s the new single from Robin Thicke, the fascinatingly uncomfortable “Get Her Back.”

Here the R&B singer, who spent much of 2013 riding high on the success of the inescapable “Blurred Lines,” lays out his regret over his recent separation from his wife, Paula Patton, for whom he reportedly titled his upcoming album.

“I never should have raised my voice or made you feel so small,” Thicke croons over an ingratiating guitar figure, “I never should have asked you to do anything at all.”

It’s hardly Thicke’s strongest songwriting. But how refreshing to encounter the clumsy words in a seemingly heartfelt song rather than one more well-vetted statement.

Twitter: @mikaelwood

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.