Guess who upstages ‘Me and Orson Welles’?

“Me and Orson Welles” is a frothy backstage pass, courtesy of director Richard Linklater, to the early days of the great director (that would be Welles) during a stint as the mercurial head of the Mercury Theater Company in 1937.

Adapted from Robert Kaplow’s novel, the “Me” is a teenager whose coming-of-age story unfolds during the staging of Welles’ groundbreaking reimagining of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar as a ‘30s-era Fascist dictator. The teen in question is Richard Samuels, played by “High School Musical” heartthrob Zac Efron, a senior who slips out of class and into NYC only to get swept up in Welles’ retinue, with a small part tossed his way as a bone.

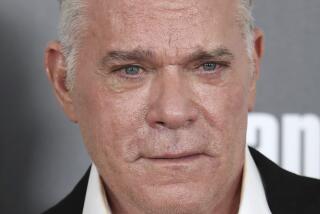

The film’s other key players are Claire Danes as the director’s whip-smart assistant and sometime lover Sonja; Christian McKay as Welles, who bears a striking resemblance to the man and has a good handle on his pretension and ambition; and Zoe Kazan as Gretta Adler, an aspiring writer and the occasional object of young Richard’s affection when he’s not mooning over Sonja.

Richard’s problem is really Efron’s problem too, and thus the film’s (which may be why it stumbled around the festival circuit for nearly a year before finding a distributor). The character spends most of the movie trailing Welles around like a puppy, only occasionally biting the hand that feeds him. The role was supposed to mark Efron as a grown-up actor and while he’s pleasant enough he remains very much in the puppy-training phase, with Danes and McKay holding on to most of the movie’s treats.

Linklater always brings a great sense of place to his projects, whether it’s “School of Rock’s” classroom antics with Jack Black, the stoner high school students of “Dazed and Confused,” or Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke wandering Paris in 2004’s “Before Sunset.” Though the production team gives us a lovely re-creation of the New York theater district circa 1937, the filmmaker truly finds his footing inside the Mercury where the casting, the staging and the catastrophes play out.

But it’s the clashing egos as much as the brilliant theater that interests Linklater here. The script, written by Holly Gent Palmo and Vince Palmo, has Welles moving through the theater troupe like a shark, feeding on anyone who is weaker than he is, which means everyone. Roles are expanded and contracted with abandon, actors hired and fired, lovers taken and discarded with a pregnant wife not treated much better.

McKay, a British stage actor who was doing an off-Broadway production about the movie legend when casting started, and Danes, whose acting always seems so effortlessly good, are the best things about the film.

But as in life, the presence of Welles never fails to overtake things and McKay’s command of the subject is so Welles-ian that when he’s in a scene everyone else fades a little. And neither the director (that would be Linklater) nor the film ever quite recover from that.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.