‘Lucha Underground’ captures diverse L.A. in a wrestling ring, with tights and melodrama

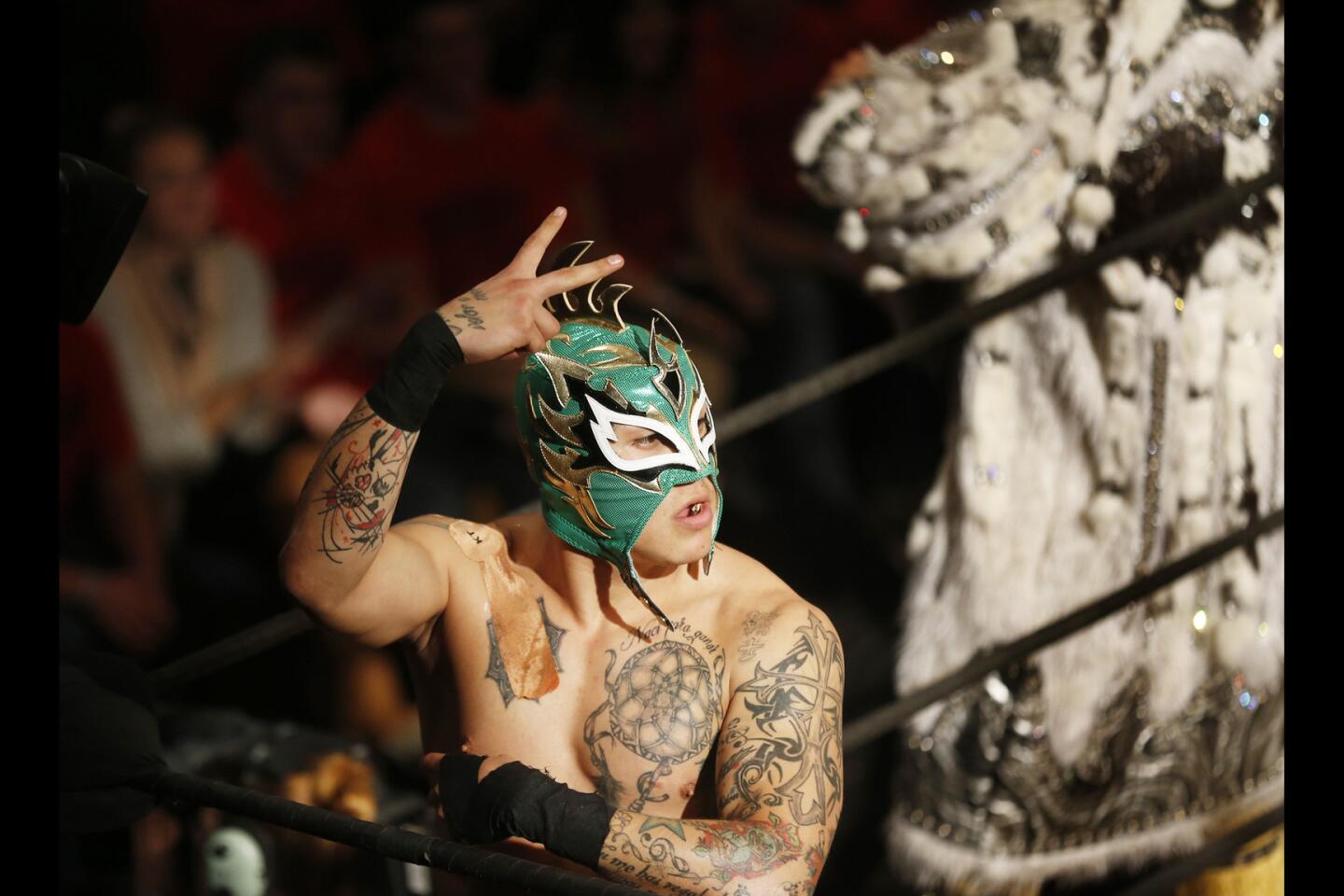

Across the Los Angeles River, in a warehouse of ghosts and corrugated steel, King Cuerno fastens his mask and strides bare-chested past girders and broken windows toward the ring, where wrestlers spin in pinwheels and dance on ropes in a frenzied ballet of peacock colors and flying head scissors.

The crowd in Boyle Heights — twentysomething Latinos, comic-book geeks and a rowdy bunch of Marines — stomps in glee. Sliding through the clamor with sinister aplomb is promoter Dario Cueto, his voice like a bullet through velvet. He rules over “Lucha Underground,” a professional wrestling TV series where heroes and villains tangle in noirish melodrama and Aztec mythology in search of the Gift of the Gods championship belt.

The scripted program blends the flamboyance of the aerobatic lucha libre wrestling style prominent in Mexico with the brawn and punch prevalent north of the border. Airing on El Rey Network, which reaches 40 million homes in the U.S., the show is a glimpse of a hybrid America at a time when immigration reform and Donald Trump are challenging the parameters of citizenship and the nation’s changing demographics.

“Latino culture is very pop culture now,” said Chavo Guerrero Jr., a third-generation wrestler whose grandfather was a famous luchador in Mexico. “People think, ‘Oh, “Lucha,” it’s a Mexican show.’ Uh, no. Look at the fan base. It’s wrestling. Wrestling is African Americans, whites, Asians. It’s all different. In the wrestling world this show is the first thing that’s been different in years.”

Beginning its second season, the English-language show is an echo of Los Angeles, a city of incongruent architecture and shifting syntax, where food trucks traversing the fringes park amid the glint of razor wire and the blush of graffiti. Rising beneath palms on ground where trains run no more, the building that houses “the Temple” and its ring is an early 1900s metal factory that has appeared in the movie “Horrible Bosses” and the TV show “NCIS: Los Angeles.”

“Boyle Heights was the first stop for many immigrants who came to Los Angeles,” executive producer Eric Van Wagenen said before the taping of a new episode on a recent Saturday afternoon. He noted that the show is trying to unite the neighborhood in a county that is about 50% Latino. “We’re embracing them with a throwback nostalgia for lucha. It’s kitschy fun for a phenomenon that came before.”

A time lapse of the “Lucha Underground” ring in Boyle Heights, where heroes and villains tangle weekly in noirish melodrama and Aztec mythology in search of the Gift of the Gods championship belt.

George Arenivar waited in the dusk near a hamburger truck during the intermission before a six-on-six tag team match. A cool breeze lifted as young men in white T-shirts and loose jeans finished their beers and drifted toward distant fences. A graphic artist whose day job is at UPS, Arenivar stood near a white guy with a shaved head, two furiously texting blond girls and a trio of hipster types who looked as if they had wandered over from a Spring Street cafe.

“‘Lucha Underground’ is culturally diverse,” said Arenivar, one of more than 400 fans who attended a recent taping; “Lucha’s” highest-rated show drew 250,000 viewers. Arenivar credited the program’s theatrics and polished editing. “Wrestling used to be more campier. But this is cinematic, and the crowd is involved. They have storylines and wrestling. It’s entertainment.”

Professional wrestling has long been the odd cousin of who we are, that sequined and booted carnival of scowls and grimaces, of hammerlocks and backflips, of mad men aflight; all make-believe, but in the spark of the moment, wonderfully alive with the scent of blood and the glimmer of pomp. “Lucha” captures this with eight cameras, editing booths and back stories woven with Aztec folklore that seek to compete with the dominant programming on World Wrestling Entertainment.

With menace and winked charm, “Lucha” is emblematic of the style of El Rey Network, begun in 2013 by filmmaker Robert Rodriguez. The network conjures the mischievous shadows and gonzo bloodletting in two of Rodriguez’s films “From Dusk Till Dawn,” a tale of vampires and hoodlums starring George Clooney and Quentin Tarantino, and “Sin City,” a noirish thriller starring Bruce Willis and based on Frank Miller’s graphic novel of the same name.

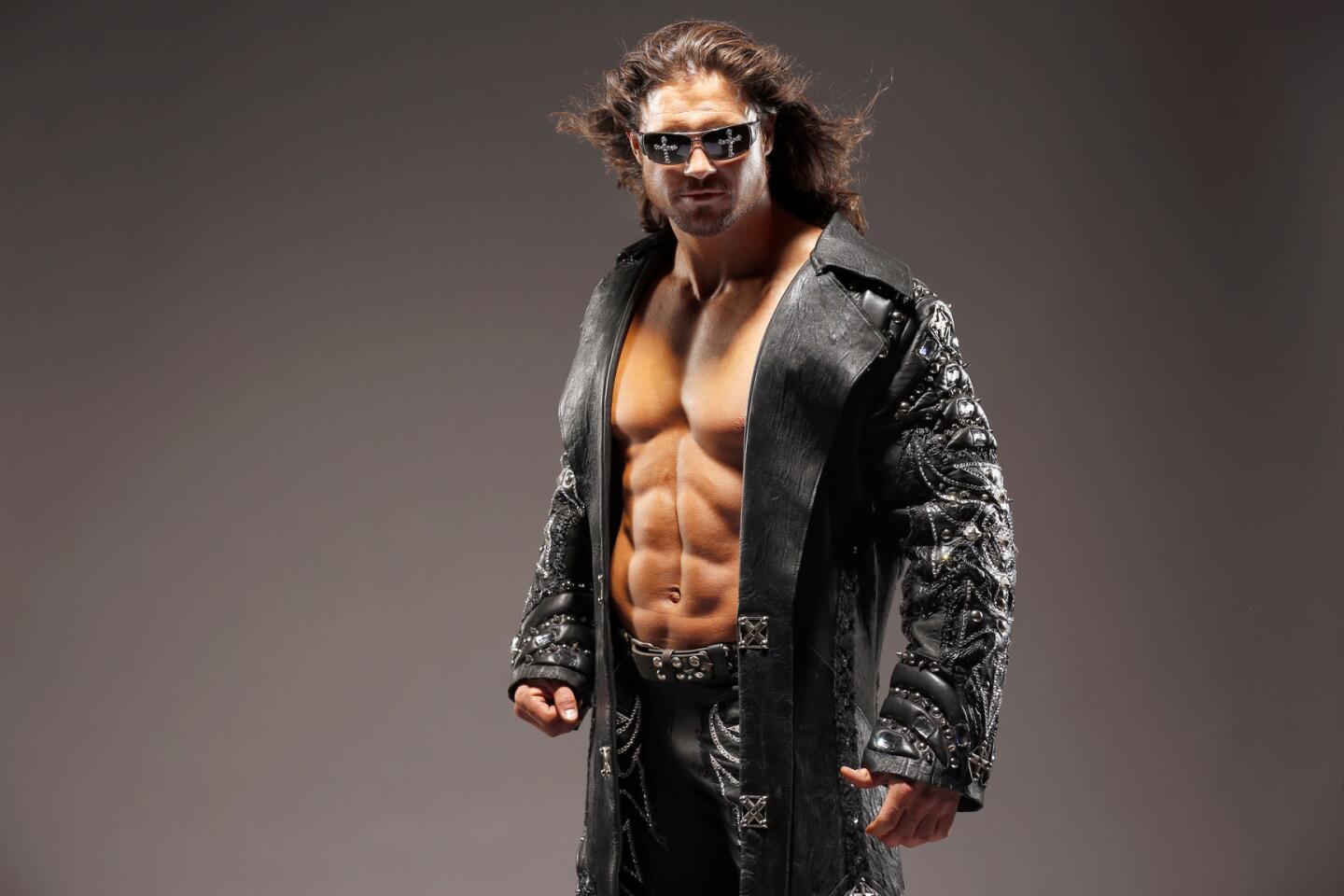

“It’s not just pure lucha libre out here,” said Brian Cage, known as “The Machine,” brandishing a mohawk haircut and restless muscles. “It’s a blend of styles. It crosses cultures. Instead of being a B-version of the WWE, it’s something different. It’s more of a TV show about wrestling than a wrestling TV show. It’s not watered down. It’s not overdone with drama and soap opera BS. It’s more [vivid] as opposed to corny and cheese ball.”

The six-on-six tag team bout was a blur of colors when Prince Puma — donning animal headdress — marched into “the Temple” through a scrim of smoke with a cadre that included a black wrestler brandishing an Afro pick, a woman dressed in a dominatrix skirt and a cat-like mask, and a white guy who looked like he belonged on a ZZ Top album cover. They faced off against King Cuerno and his crew, notably Taya, who wore red lipstick and eyelashes as plush as a crow’s wings, and her partner, the magically cocky Johnny Mundo.

“We’re this absolutely glamorous, mean-streaked couple who are here to show we belong in ‘the Temple,’” said Taya, a classically trained ballerina who hails from Canada and like other competitors wrestles for Asistencia Asesoria y Administracion, a lucha libre promotion in Mexico. “Johnny Mundo and I are viewed as foreigners in this Aztec-Mexican legend built scenario.”

Off to the side of the ring, Cueto (played by Luis Fernandez-Gil) lurked about like a gangster’s whisper. He disappeared into an office of pulled blinds, booze and a set of bullhorns on the wall. The promoter’s lair had the whiff of old smoke, creaky leather and a man up to no good; Cueto, of course, was maneuvering to regain control of “the Temple” after a murder at the end of Season 1 forced him to vamoose as the luchadores scattered.

“I’m a lifelong wrestling fan. I’ve always been fascinated, and I’ve flown all over the country to see matches,” said Gabriel Daigle, who brought his 14-year-old son to the match. “But over time I lost interest.” He added that the WWE and other wrestling programs “got stupid and challenged my intelligence. But ‘Lucha’ blew me away. You can tell it’s shot by filmmakers. It’s totally revolutionary.”

Despite its edge, though, “Lucha” evokes a past of ragged arenas and masked men, when challengers appeared out of the Mexican countryside and legacies were handed to wrestlers like King Cuerno, who trained in the arts of combat and started wrestling when he was 4.

“The masks and the whole mystery behind everything comes from Mexico,” said the king, zipped into a mask and peering through eye-slits. “We love all this paraphernalia and flamboyance.”

He disappeared toward the workout room — a shamble of weights, graffiti, duct tape — as Guerrero, his mustache neatly trimmed, spoke of speed and flying moves and how much things have changed since the time when his father wrestled the lucha style in Japan and the U.S., including in Los Angeles at the Olympic Auditorium.

“Back in the day it was just a headlock,” said Guerrero. “A body slam was a huge move back in the 1960s. You body slammed somebody and it was, ‘Whoa, that’s crazy.’ Today if you body slam they’ll boo you out of the building. You got to light yourself on fire, you know. It’s like X Games now, and we’ve taken it to a different level.”

The thumping bass line of “the Temple’s” band, a collision of guitars and horns that could startle the dead, roused the crowd. Ring announcer Melissa Santos wore a tight green dress and slipped through the ropes with a microphone, followed by a man in black who told the crowd: “We love you like family.... [But] don’t take spoilers and send that … on the Internet.... Everybody deserves that emotional ejaculation when they see a show.”

A guy in the crowd, wearing a “Lucha” mask T-shirt, threw his arms to heaven and stood like a statue.

“USA, USA, USA,” chanted a row of Marines.

A man turned to his girlfriend: “I will not sit down. I will not be contained.”

A little wrestler, Mascarita Sagrada, accompanied by Famous B and Beautiful Brenda, bounded into the ring in a mask, zip-up white suit and matching patent leather boots. He went at it with Joey Ryan, but after a few leaps and kicks the little man hit the canvas and the ref moved in. The crowd booed, screamed and whooped, and after a moment Guerrero, dressed like an Aztec gladiator, faced off against Cage, who was squeezed into a black and yellow singlet and growled like a man who had lost a bag of money.

“You still suck,” somebody yelled.

Guerrero and Cage went balletic, spinning, flipping off ropes, slamming each other. They spilled out of the ring and back into it, and when it was over, sweat on the canvas and a roar in the air, one of them (no spoilers allowed) lifted the belt and let the cameras feed upon him.

Twitter: @JeffreyLAT

MORE ENTERTAINMENT NEWS

Jason Sudeikis is an everyman for the early 21st century

In ‘Pride and Prejudice and Zombies,’ the undead lock horns with some very tough Bennet sisters

Super Bowl 2016 commercial challenge: Amy Schumer vs. Helen Mirren, Doritos vs. Mountain Dew

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.