‘Slumberland’ by Paul Beatty

Slumberland

A Novel

Paul Beatty

Bloomsbury: 244 pp., $24.99

I first heard of Paul Beatty in the 1990s, when Europe was awash in young black rebels trying to forge a new identity against the backdrop of insidious racism. We wanted to be black and proud, as the song went, but we wanted none of the nationalist narrative of the generation that came before us. What, then, were we to do?

¶ Into this mix came Beatty, and his novel “The White Boy Shuffle,” which in London very quickly became a kind of guide for how to approach this new blackness: a blackness that allowed us to read Heidegger, to argue that we liked Wallace Stevens better than Langston Hughes, to love action films in spite of their often-racist subtexts. We argued that García Lorca had more in common with Africa and Bob Marley than he did with modern Spain; we shared picnic lunches with Berliners; we longed for a world in which we could be who we wanted and still retain, with dignity, a shared identity that superseded sorrow, enslavement or difficulty. We desired all the nostalgia of Chaka Zulu, all the sweet defiance of Nina Simone and all the philosophical insights of Eshu Elegba. We had begun to suspect that the blues, and necessarily jazz, were as much about joy as they were about sorrow, about gain as much as about loss, an eclectic and ambiguous aesthetic we would need to embody if we were to “chant down Babylon.”

¶ “Slumberland,” Beatty’s new novel, speaks to many of these themes, which are, of course, the same ones raised in “The White Boy Shuffle.” But while the internal terrain is still the black body, specifically the male black body, the terra firma of the novel has changed from inner-city America to the heart of Berlin. What better place to set a novel about otherness than Berlin, a city that is other to itself? A city that has to negotiate the terrible legacy of the Nazi era, while still finding ways to celebrate Goethe, that has to reevaluate its German-ness in light of 40 years of Turkish immigration and now reunification? It’s the perfect setting for a noir to take place, no pun intended, and Beatty navigates the city well as his locale.

The protagonist of the novel, DJ Darky, is a Los Angeles DJ who comes to Berlin to be a jukebox sommelier. He is in search of a virtuoso saxophonist, Charles Stone -- nicknamed the Shuwa -- who is in many ways his doppelgänger. DJ Darky has created a sonic masterpiece, layering nearly every sound he can find into a flawless testament, a musical ars poetica. Now, despite offers from the gangsta rap community, he wants the Shuwa to play some avant-garde mystical voodoo music over the beat. DJ Darky arrives in Germany, having already declared the end of blackness, to find himself once more the subject of racism amid constant reminders of his obsolete ethnicity. His real quest, we soon learn, is for meaning and a place in the increasingly chaotic post-Cold War world.

“Slumberland” is laugh-out-loud funny in many places, and its wit and satire can be burning, regardless of where they are pointed: blackness or whiteness. The book places Beatty somewhere among Ishmael Reed, Dany Laferrière and William S. Burroughs, and it is rife with sex (particularly interracial sex as weapon, as guilt and celebration, but never as love), music (it is, in fact, a love poem to music as identity, as savior, as self, as the perfect language) and religion, whatever mask it wears.

Darky leaves Los Angeles not only to find the perfect beat but also the perfect seduction. He wants to be seen not through white America’s eyes but through his own eyes, outside the weight of all the racial narratives that he has to filter in the U.S. Berlin, however, turns out to be just as fraught.

At times, the tone of the book comes off as glib. Yet after a while, we realize this is actually a device of displacement. Because Darky cannot find himself through the body of another -- whether a woman or even another culture -- we are left with a peculiar ambiguity that challenges our narratives of self and other. It’s an effective tonal device, although it can leave us wanting more of a connection. The difficulty for Beatty is that our image of the heart of black melancholy is too reminiscent of a Charlie Parker solo, which has over time become something of a cultural cliché -- regardless of its enduring transformative powers.

For all that, there are incredible moments of tenderness. When Beatty describes Darky’s incredible ear and his “phonographic memory” -- an ability to recall every sound he has ever heard and when -- he evokes a psychic and spiritual insight that speaks to the character’s heart. Music, and Darky’s relationship to it, becomes the place where Beatty argues for the soul of this one torn black man, making of him a kind of symphonic W.E.B. Du Bois.

And yet, “Slumberland” does have its faults, as all good novels must. There is no acknowledgment that Darky, with his musical gifts and near genius intelligence and recall, can and must figure out a different way to navigate the world. Particularly glaring is a scene in which he imagines that being in love must be like reading Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” in a park while trying not to scream out his own superiority in the face of everyone else who might be there.

What Beatty doesn’t acknowledge is that Darky’s power to so intelligently dissect his place in the world is a privilege many blacks do not carry. There is, in a sense, an invisible body of blackness that is also the terrain for Darky’s journey of discovery. It is essential for the novel to explore this idea since it is arguing against a monolithic perception of blackness. I think there is some truth to Paul Gilroy’s ideas that race and class become conflated and can act even more powerfully on an individual than they can on race alone.

At its core, “Slumberland’s” sadness is that of a black man cast loose in a universe of whiteness, carrying the pure sorrow of never being seen, and an even deeper sorrow of not being able to see himself. Perhaps this is the point of the glib tone -- that one can never truly get to the heart of a difficult question by using tropes and ideas that, while ringing of personal truth, are riddled with cultural sentimentality. *

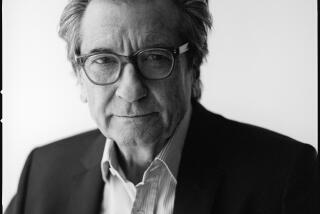

Chris Abani, an associate professor at UC Riverside, is the author, most recently, of “Song For Night.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.