Wrapped in a bungalow’s secrets

I CHOSE OCEAN PARK for the light in October, a certain rose-yellow glow slanting from the Pacific.

When I found the neighborhood in 1980, Main Street was mostly empty storefronts punctuated by vacant lots, thrift stores, a couple of bars. Clapboard bungalows with peeling paint nestled against concrete-block apartment houses.

I was new to Los Angeles; I had sold my first screenplay to MGM and had spent the summer rewriting in a hotel room in Westwood. Now it was October, and as a birthday gift to myself, I drove my rental car west to rest my gaze on what I had missed most while living in New York City: a horizon. At the Pacific Ocean, I made a left and parked just south of Pico, in the neighborhood where I would spend the next 25 years. I stepped into the golden light, and felt I had come home.

I found a one-bedroom close to where the Pioneer Bakery exhaled its hot sourdough fragrance into the damp ocean air. A producer friend suggested I meet his pal Nick, who lived on Hill Street a few blocks away. We reluctantly agreed to be introduced, and to make sure our meeting couldn’t be construed as a blind date, the three of us convened at a breakfast joint on Main Street.

On the wall behind Nick, a grainy blow-up of a photograph marked “1897” showed a newly constructed Arts and Crafts-style house perched alone on a hill, overlooking a furrow of dirt meant to be a street. Ocean Park was just coming into existence: This was the first house built on the hill that now overlooks Main Street. That bungalow still stands, now crowded by condos, not far from the 1901 Craftsman house my husband Nick and I bought 18 months after our first breakfast.

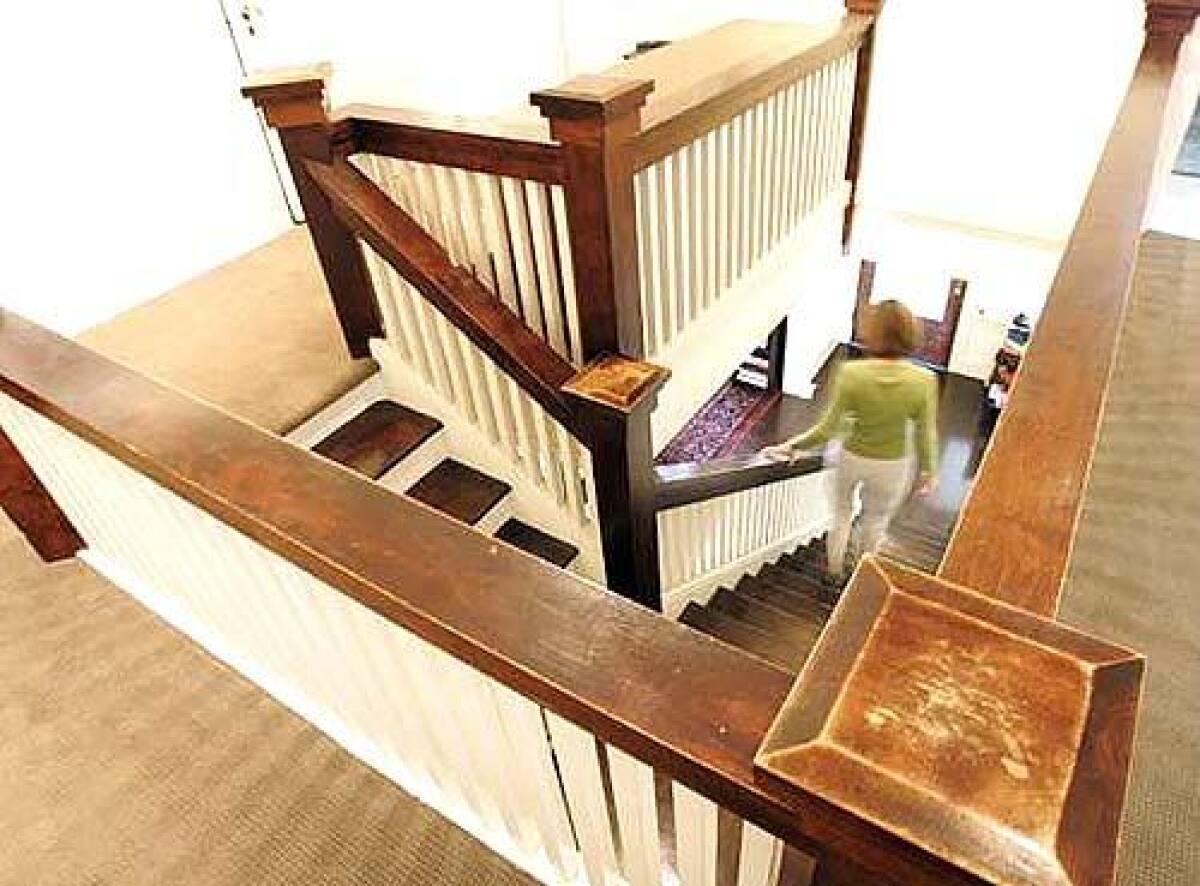

We knew little about Arts and Crafts design, but were drawn to the house by the light down the stairwell, the harmonious proportions of the rooms, the simple grace of its dark polished woodwork. Though most of the owner’s furniture was gone, a sense of family lingered. The Seller had reared three daughters here, one in college, another working, the youngest just graduated from high school. I noted the padlock on her closet door. “My girls forget to do laundry, then they borrow my clothes,” the Seller explained.

I nodded politely, with inward horror. I was two months into my first pregnancy; the daughter I was carrying was busily raiding my bones and blood for nutrients. What mother could deny her precious child anything she needed? It would be 15 years before I would find myself searching in vain for my favorite cashmere sweater, only to discover it wadded under our 10th-grader’s bed. A padlock was a brilliant idea.

Nick and I took possession of the house in its child-marred state. The departing Seller had left behind a massive old desk she couldn’t budge. We cleaned out the pencil shavings and called it ours. But it wasn’t ours. In the dark varnish on the center drawer, the previous owner’s child had scratched her name: “Anna.” Under the eaves behind the closet, I found a bitter secret grooved in childish handwriting: “I hate Dena.” Sisters had lived here — sisters who grew into local beauties, with long black hair and a proclivity for displaying themselves on the front porch gables. This I heard from a young policeman who paused wistfully on our sidewalk as my toddler daughter played at my feet. He had gone to school with the girls. In the summer, he said, they would climb out their second-story bedroom windows and stretch out on the roof in their bathing suits.

Our bungalow was 80 years old when we bought it, and (we soon discovered) in precarious health. Its cast iron plumbing was held together by rust. Sash windows were painted shut, their pulley ropes worn through. Seepage from clay pipes had undermined the brick foundation. Brittle knob-and-tube wiring ran chaotically through cracked plaster walls. Termites had colonized under wooden floors, to which pink-flecked linoleum had been affixed with tar. I dreaded the basement laundry room. “It feels haunted,” I told Nick. We hollowed out niches in the basement’s dirt walls to display fake Hummel figures, ceramic alligators and plastic Army men — “The Sculpture Garden,” we called it.

In the powdery soil I unearthed a military medal from World War II, an artifact from the first family to live here, Ocean Park pioneers who built the house and inhabited it for 60 years. As we began repairs, I found other evidence of this original family. Behind plywood nailed to a closet wall, we uncovered a crumbling patch of Arts and Crafts wallpaper — proof that the closet had been added later. In stripping the linoleum, we saw that the family room had once been two rooms, one floored in maple, one in oak — the original sitting room and dining room, I realized. As I sat awake in the dark house, nursing my infant daughters, my imagination would turn to the families who had lived in these rooms before us; three generations of mothers nursing their babies in the night.

Gradually I felt myself becoming intimately attuned to the house. I probed its psyche, reading up on Ocean Park and the Arts and Crafts movement, trying to draw upon the original designer’s intentions — in much the same way that I approach an adaptation as a screenwriter, seeking out the author’s influences, the better to know the secret life of the novel.

One day as I stared at the fireplace, envisioning its original Craftsman tiles (long ago stripped and “modernized” with bathroom tiles), in my mind’s eye I saw brass and mica sconces hanging on either side. Months later, drilling into the wall to install the Craftsman lamps I had found in an antique shop in Seattle, we discovered on either side of the fireplace the original 1901 wires already in place, in good condition, ready to receive the sconces. I had begun to read the house’s mind.

We were fortunate to find skilled contractors, Steve Hunter and Max Van Runkle, who understood the superior quality of workmanship an Arts and Crafts house requires. We often had to wait between projects to set aside money. But over several years, Max and Steve stripped away midcentury “improvements,” replaced plumbing and wiring, shored up the foundation, renovated the kitchen, always matching Craftsman techniques.

Sometimes the house seemed to shift uneasily in complaint, especially when we disturbed the basement. Ceiling fixtures rocked. Doors slammed when no one was near. All of us woke in the night to the sound of spectral footsteps tramping the staircase. I didn’t believe in ghosts, but I did believe in the past. I respected the original architect, and I wanted to keep faith with the house.

Even as we worked our alterations, the house subtly shaped our family in return. Friends who had bought U-shaped ranch houses slept in separate worlds, parents in one wing, kids in the other. But our bedrooms were intimately grouped, facing each other around a central stairwell that conveyed every whimper and whisper. We shared a single small bathroom upstairs, so the “family bath” became routine during the toddler years. Living here forced us to adopt the intimacy and simplicity that are hallmarks of the Arts and Crafts philosophy. We couldn’t live a life of mindless accumulation — with tiny Craftsman closets and little space for bookshelves, we didn’t have the room.

As we adjusted ourselves to our home, the house rewarded us with what I can only describe as a profound embrace. For 20-plus years our two daughters have dashed up and down the stairs, read in the sunlight at the backdoor, played in the eaves, climbed out windows onto the gables under the fringe of jacarandas we planted for them when they were born.

When our older daughter was 10, the contractors replaced the last of the knob-and-tube wiring in the attic. We put down a floor and called the space “the Museum of Childhood.” Each passing year, we stored the things the girls could not be parted from: Barbie dolls and picture books, artwork, a velvet dress, eighth-grade science books. “You’ll have to clear this out one day,” I warned our daughters, who are young women now, the closest of friends.

In May, Zoe graduated from college. Her younger sister, Maya, finished high school. In preparation for college, Maya has been cleaning her room. As I lift one of her boxes into The Museum, I come across a dusty stack of childhood journals wedged under the rafters. One book is blank except for the first page, which begins, in early cursive, “I hate Maya.” Sisters once lived here.

Robin Swicord adapted the novels “Little Women,” “The Perez Family” and “Matilda” (with her husband, Nick Kazan) for the screen. Her adaptation of “Memoirs of a Geisha” will be released later this year. She is at work on “The Jane Prize,” an original screenplay for Swicord to direct.

More to Read

Sign up for our L.A. Times Plants newsletter

At the start of each month, get a roundup of upcoming plant-related activities and events in Southern California, along with links to tips and articles you may have missed.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.