Can you imagine?

LATE one night, author Susan Straight was listening to the whistle of passing trains and smelling the jasmine that smothers her white picket fence close to where the road dead-ends into the sagebrush chaparral near her Riverside home. Her imagination strayed from the contemporary novel she was writing; what if her three daughters, sleeping peacefully across the hall, had been born 200 years ago, when girls just like them were someone’s property?

Straight wandered into their bedroom, where they were safe and softly breathing, and ran her hands over their stuffed animals, their Kobe Bryant poster, their books, touched their peaceful faces and long curly hair. What if her girls were the children of rape, or the sexual prey of the people who owned them? Straight -- a white writer who had three children with her ex-husband, who is black -- set aside her other novel and began a painstakingly researched period novel, “A Million Nightingales,” about the life her daughters might have led in America’s not-so-distant past of racial feudalism.

“I looked at all three of them and thought, ‘If they’d been born in 1800 Louisiana, people would have had one thing in mind. One thing,’ ” Straight said. “Can you imagine what their lives would have been like, with their looks and their brains?”

The life Straight imagined is told through Moinette, the daughter of a comely Louisiana slave whose owner lent her to a visiting sugar planter in the spirit of casual hospitality, like he might offer him a glass of good wine. Moinette, the daughter of this forced encounter, grows into a wary young woman intent on reconstructing her fractured family and gaining control over who has access to her own body. Her character is so tenderly and intimately wrought, it’s easy to believe she was inspired by Straight’s girls, and her persona is evoked on the cover of the book by a photograph of Straight’s own middle daughter, Delphine.

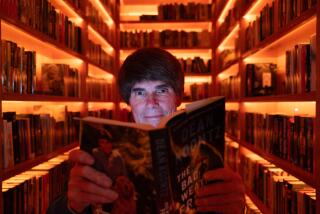

“I remember someone said, ‘Why would you portray such an intelligent slave?’ ” said Straight, 45, a wiry, petite woman with jeans and boots and wispy blond hair, as she set steaming platters of garlic shrimp and rice on a wooden table in the bright kitchen that is the center of her busy family life. “Of course there were brilliant slaves, but they couldn’t be taught to read and write. They could have been great shipbuilders and architects and scientists. Just as there were as many brilliant women back then as there are now.”

Moinette’s keen intelligence is devoted to physical and emotional survival. “You could enslave their bodies but not their minds,” Straight said.

Straight’s novel joins a number of contemporary books that grapple with the imagined daily realities of slavery. Like Toni Morrison’s 1987 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “Beloved,” about a slave mother who pays an unbearable price to save her daughter from living the life she herself endured, today’s books deal with the chilling details rarely found in historical documents, such as the less-than-probing interviews of former slaves conducted in the 1930s as part of the Works Progress Administration. Things like women not feeling safe in bed at night, knowing they were fair game for outright rape. Or the daily domestic dramas in which women were forced to weigh carefully the consequences of sexual refusal or submission.

In recent years, out-of-print memoirs of slaves themselves, such as Harriet Jacobs’ 1861 “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” one of the first books to deal, in harrowing detail, with the sexual abuse of slave women, have been reprinted. Yet even today, the memories of many elderly African Americans who lived through the violence of Jim Crow are vanishing with their deaths.

But life under slavery and Jim Crow is being increasingly visited in fiction, in contemporary novels such as Valerie Martin’s “Property” and Edward P. Jones’ Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Known World,” or in modern classics like the late Octavia Butler’s “Kindred,” a disturbingly convincing 1979 science fiction novel in which a contemporary Los Angeles woman finds herself transported to the days of slavery. The claustrophobia of segregation is also reemerging in fictional releases, in reissues of earlier works such as Ann Petry’s 1946 “The Street” and Langston Hughes’ short stories, including “Passing,” in which a young man doesn’t speak to his dark-skinned mother on the street so people won’t know he is of African descent.

Straight’s work is an anomaly, in some ways, because though she is white, her work often portrays African American life, from the point of view of black characters (though her 2001 National Book Award finalist, “Highwire Moon,” told the story of a Mexican immigrant woman). In 1996’s “The Gettin Place,” black migrants to California are haunted by memories of the Tulsa, Okla., anti-black pogroms of 1921. Her 1992 novel “I Been in Sorrow’s Kitchen and Licked Out All the Pots” features a black heroine from a Gullah-speaking South Carolina backwater.

There is her 1994 “Blacker Than a Thousand Midnights,” the story of a hard-working young black firefighter, Darnell Tucker, who must also battle the incendiary street life that has seduced his friends, a character Straight said was inspired by her former husband, Dwayne. The Quarterly Black Review of Books said that book “shows the compassion, the dignity, the sorrow, the humor, the wisdom, the waste, the triumph, the failure, the color of black life.”

Some criticism has arisen, particularly in Straight’s early years, over the issue of the appropriation of black culture. In “White Authors Cash In on Black Themes,” a 1993 article in Emerge magazine, Quinn Eli acknowledged Straight’s narrative talents and empathy but said she was unequally rewarded. Her book was “privileged,” Eli said, and “received widespread attention from reviewers and literary pundits that equally compelling books by black writers are rarely afforded.... This means that although she’s a writer of phenomenal talent, it is only incidental to her success.”

One black Los Angeles writer said she knew the issue of appropriation made some of her fellow writers uneasy, but she declined to openly criticize Straight: Wouldn’t that mean black writers can’t write from the point of view of white people? In recent years, Straight has been on Tavis Smiley’s show and asked to write a piece for Oprah’s O magazine.

At readings, Straight said, the issue seldom comes up, and when it does, white people usually raise it. At one 1992 reading, in Washington, D.C., a black woman stepped forward to defend her, she said.

“I’ve been asked about it very rarely,” she said. “I think it comes up if people do a bad job.”

Of course, Straight is hardly the only writer to stray from her ethnicity. Norwegian-born writer B. Traven wrote groundbreaking novels about the then-unexamined lives of dirt-poor debt peons in southern Mexico with a depth that made the books recommended reading as late as the 1990s Chiapas guerrilla insurgency. Nagasaki-born Kazuo Ishiguro’s “The Remains of the Day” is one of the most vivid dissections of the self-imposed loneliness of the British class system.

Like Ishiguro, whose parents moved to England when he was a boy, Straight grew up in the world she writes about. She came of age in Riverside, a region of California where interracial families were more common, in part because of the preponderance of local military bases, where U.S. World War II soldiers returned home with their Japanese war brides, along with the more rare black-white couples who, Straight said, “weren’t going to go back to the segregation in the South.”

Riverside raised

Straight feels deeply rooted here. She was born within walking distance of her home to a Swiss immigrant mother. She grew up hiking the stony mountains with her brothers and hanging out in a working-class clapboard district, “Okie Town,” that is now being torn down by developers. She says she listened to stories of life under segregation, told by older black people, who had moved to Riverside from the Deep South, including one family who packed up overnight because they believed they could not protect their daughter from what seemed to be an imminent threat of rape from a powerful local white man.

She met her husband, Dwayne, in eighth grade, and in high school, the budding writer and African American basketball player were a familiar couple. They married when she was 22 and had three children, Gaila, 16, Delphine, 14, and Rosette, 10. In a December essay in the New York Times Magazine, Straight wrote that her black in-laws “have forgotten that I am white.”

Though the marriage ended after 14 years, Straight remains close to her in-laws and deeply connected to Dwayne. On a recent afternoon in Riverside, as Straight -- who is also a creative writing professor at UC Riverside -- ran school and grocery errands with her daughters, he called her several times to share the day’s parenting tasks.

The far more immutable racial universe that emerges in Straight’s “A Million Nightingales” underlines the collective amnesia with which many Americans approach the country’s racial history and its modern legacy. To research the novel, Straight traveled to Louisiana’s rural Plaquemines Parish, where the Mississippi Delta spreads out into wetlands. She stayed in Woodland Plantation, whose owners once trafficked in humans -- the kind of detail that was, until recently, often ignored in plantation tours.

“It was very creepy,” Straight said. “I stayed up all night writing. I wrote a lot of the novel by hand. I could see the slave cabin from my window, and the idea that someone could look at that house all the time was amazing.”

Soon, she will go back to the contemporary novel she began writing, five years ago, about the characters who, in Straight’s fictional world, would be Moinette’s great-grandchildren. Characters who tell younger family members stories about life under slavery that had been passed down through the family.

“I kept thinking about how slavery affected people, generations later,” Straight said. In the literary landscape of Straight’s “A Million Nightingales,” past is prologue.

*

Susan Straight

Where: L.A. Times Festival of Books, Korn Convocation Hall, UCLA

When: 4 p.m. April 29

Also

Where: Dutton’s Brentwood Bookstore, 11975 San Vicente Blvd., Los Angeles

When: 7 p.m. May 4

Contact: (310) 476-6263

Also

Where: Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles

When: 6 p.m. May 14

Contact: (310) 443-7000

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.