Replicate the Cadbury Creme Egg? Crazy, you say. Try it.

Maybe it was the 12 pounds of chocolate. Or the 40 pounds of sugar. Not to mention all the cream, milk and corn syrup — and the two dozen vanilla beans. My little project was turning into more of an obsession. Little project? I was only trying to re-create the Cadbury Creme Egg.

Introduced by British chocolate-maker Cadbury almost half a century ago, the Creme Egg, like Peeps, signifies Easter from a confectionary standpoint. A thin layer of festively colored foil peels away to reveal a dense milk chocolate shell shaped like a smallish egg. Unassuming at first, the plain shell lacks the sheen and snap typical of commercial chocolate, but it takes just one bite to tell this chocolate is richer, not overly sweet, almost fudge-like. The initiated know to carefully nibble through the shell to the sweet gooey filling — creamy white at first, then a vibrant yellow in the center. It’s a confectionary wonder, available just a few months of the year.

With Cadbury in the news lately — devoted fans decrying altered chocolate formulas, shrunken egg sizes, halted imports — we here in the L.A. Times Test Kitchen wondered how hard it might be to make the eggs from scratch.

Easter: Recipes, egg decorating tips, L.A. brunch restaurants and more >>

Online recipes for Cadbury-like eggs are plentiful, and we tried a number of them. Many of the simpler variations include no-cook fillings involving powdered sugar, butter and corn syrup. And while those fillings were soft and delicate, none quite replicated the flavor or gooey texture of the commercial egg.

The Cadbury egg is a classic chocolate confection with a soft fondant center, similar to cherry cordials or what you might find in a box of chocolates. To replicate the egg, you need to start with the right filling.

Thirty batches of fondant and hundreds of eggs later — what did we find?

Essentially, fondant is nothing more than a cooked sugar syrup that is crystallized. Ingredients, ratios and cooking temperatures help to determine the fondant’s final consistency. For candies, the syrup is cooled, then stirred or kneaded to a putty-like consistency before using.

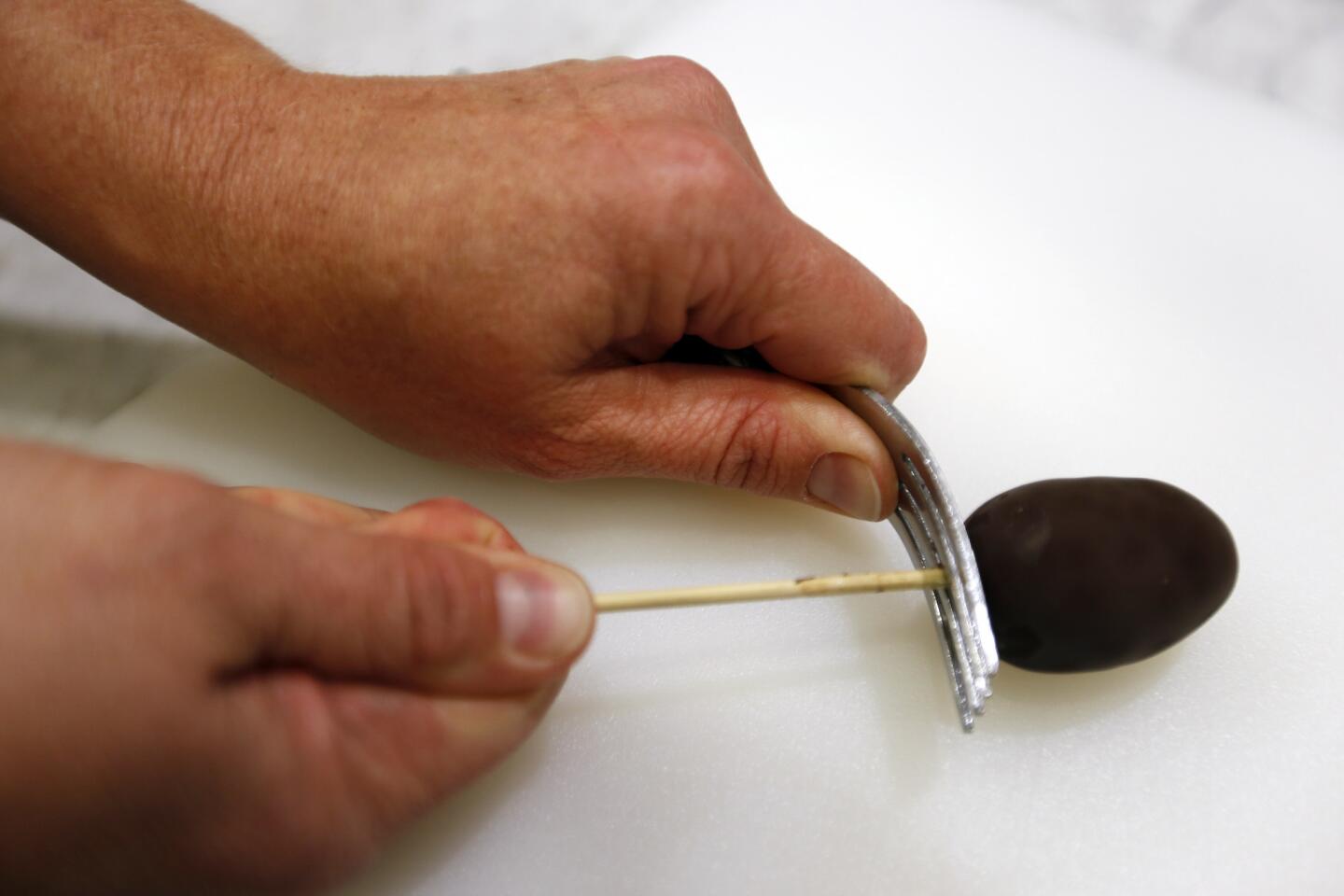

Finding the right fondant — and those right ratios and cooking temperature — was key to re-creating the egg. After trying a few recipes, we settled on a cream fondant from the excellent book “Candymaking” by Ruth A. Kendrick and Pauline H. Atkinson. It includes heavy cream and milk, lending a richness and depth of flavor not normally found in standard water-based sugar fondants. For extra flavor, we tossed in vanilla seeds.

Over the course of a couple of weeks, we tested batch after batch of fondant, tweaking and fine-tuning temperature and cooling methods. A change of just one degree in cooking temperature can affect a fondant’s final texture. Too firm and it’s too hard to knead; too soft and it won’t hold an egg shape.

Another factor was invertase, which is added to get the soft centers in many candies, and its ratio to fondant. Invertase is a natural enzyme derived from yeast that basically liquefies sugar (it breaks down sucrose into two simple sugars, glucose and fructose). But it takes time to work — typically a few days at room temperature to properly liquefy a filling. Candy, after all, has its own particular chemistry.

We formed egg after egg, each batch labeled for testing (read: eating) every day. Running out of room in the kitchen, I stored the overflow at my desk — under a “Do not eat this” sign — checking daily, in a sugar-induced haze, to see how the eggs progressed.

Fine-tuning the filling, the tests moved to the chocolate. Our trials until now had involved a combination of standard semisweet chocolate bars and chips, but the real eggs needed British-made Cadbury Dairy Milk Chocolate. With imports practically halted, sourcing the chocolate — which I finally found at a British import shop — felt like some weird Anglophile drug deal.

I made the last batch over a quiet weekend, forming, freezing and coating each egg with solemn veneration. And then I decorated them. Because sometimes you just have to celebrate your obsessions with a spray gun and some sparkly paint, don’t you?

::

A brief history of the Cadbury Creme Egg:

• Cadbury, a family-owned British chocolatier in business since the 1800s, introduces the Cadbury Creme Egg in 1971.

• In 1988, Hershey Co. pays $300 million for Cadbury’s U.S. candy operations and begins making Cadbury chocolates for the U.S. market. Hershey’s recipe for Cadbury’s Dairy Milk chocolate varies slightly from the British version, including emulsifiers used and the milk-to-sugar ratios listed in the ingredients.

• In 2010, Cadbury is bought by Kraft in what many consider a hostile takeover. In 2012, Kraft’s confectionary business is split off as Mondelez. Hershey retains Cadbury’s U.S. candy operations.

• While no changes have been made to Hershey’s U.S.-produced Creme Eggs, the British-produced confections have undergone recent changes, most notably with the chocolate formula for the egg shell. Shells had been made using Cadbury’s Dairy Milk chocolate, but in January 2015, Cadbury announces it is using “standard cocoa mix chocolate.” British egg packages also have been reduced from six to five eggs per package.

• In January 2015, Hershey essentially blocks the import of a number of British confections, including Cadbury products.

• Many fans take to social media with the hashtag #BoycottHershey and start online petitions.

Twitter: @noellecarter

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.