Stepping Out

If you made a list of the most daunting job descriptions in Los Angeles, Emily Gabel-Luddy’s would rank near the top. Gabel-Luddy, who trained as a landscape architect and has worked for the city for nearly 30 years, was appointed last year by Planning Director Gail Goldberg to lead L.A.’s new Urban Design Studio. Its broad mission is to take the city’s reputation as an unplanned, unreal and unwalkable place and erase the “un” from those adjectives.

The toughest challenge? Probably to make Los Angeles work for pedestrians. As a matter of planning, L.A. has never paid much attention to anyone who wants to move around on foot instead of on wheels. “What we’re trying to do is reverse-engineer decades of thinking about the city,” Gabel-Luddy told me as we walked through downtown recently on a scorching afternoon.

“In the past,” she told another interviewer earlier this year, “L.A. planning was all about moving cars: How can we move them faster, more efficiently, and if we have a bottleneck, can we widen the street to move them faster and more efficiently?”

But in many neighborhoods--in Eagle Rock, for one, where I live--even laypeople are coming to the conclusion that the old approach is outdated and needs to be turned on its ear. The only way major boulevards are going to work for the L.A. of the future is if the city makes them dramatically less efficient--at least as automotive arteries. Once the cars slow down, the walkers will come. It’s one more way in which gridlock might actually strengthen a sense of neighborhood in this city.

Colorado Boulevard, which is six lanes wide in some places near my house, is essentially a roaring highway lined with shops. Although the young families and the new businesses that have moved into the neighborhood during the last decade are clearly anticipating the boulevard’s great potential as a pedestrian enclave, motorists still drive 60 or even 70 mph along certain stretches. Spectacular crashes happen almost weekly.

Gabel-Luddy, whose office produced a new “Walkability Checklist” for engineers and developers in January, doesn’t just want to make the streets safe from that kind of vehicular chaos. She hopes to make walking in L.A. not just survivable but enjoyable.

Imagine that. Maybe, along the way, she can help retire the idea that you have to be crazy to walk in this city. It won’t be easy: The stereotype linking dedicated pedestrianism and mental instability has proved remarkably hardy in Los Angeles. It pops up in movies such as 1993’s “Falling Down,” in which you realize Michael Douglas’ character has truly lost it when he abandons his car in traffic and starts walking--walking!--across the city.

A more recent and more layered example is “Can’t Swallow It, Can’t Spit It Out,” a 26-minute video created last year by artists Harry Dodge and Stanya Kahn. Part of “Eden’s Edge,” a survey of contemporary L.A. art recently on view at the Hammer Museum, the piece follows a woman wearing braids, a plastic Viking hat and a green polka-dot dress as she covers vast swaths of the city on foot. The woman (played by Kahn) is clearly unstable, with blood seeping from her nose, but she is also an explorer. She is clueless and intrepid, nutty and heroic: a flaneur for our time.

As day turns to night, she walks along the concrete banks of the L.A. River, up steep, dusty hillsides and into the shadowy areas under freeway overpasses. What makes the piece so fascinating for anyone interested in the L.A. cityscape is that the spaces she moves through are so clearly inhospitable to pedestrians and, in the secrets they seem to hold, so ripe for discovery.

Conventional wisdom suggests that the only places we sane folks walk in this city are within private, commercial and “defensible” spaces such as the Grove. But I don’t think it’s too late to shape a city where people walk without buying, or without giving up the rights--free speech, for one--that aren’t guaranteed inside shopping centers.

In fact, plenty of people already walk through the public, shared spaces of Southern California--people on the extreme ends of the socioeconomic spectrum. The working class walks because it has to: to bus stops and subway lines, through neighborhoods that serve new immigrants, and so on. And wealthy Angelenos walk because they can; their unhurried strolls through shady, well-tended neighborhoods have become a sign of privilege and leisure.

The challenge for the city’s planners and architects, then, is to help create spaces attractively and conveniently walkable enough to persuade the vast swath of middle-class residents to climb out of their cars.

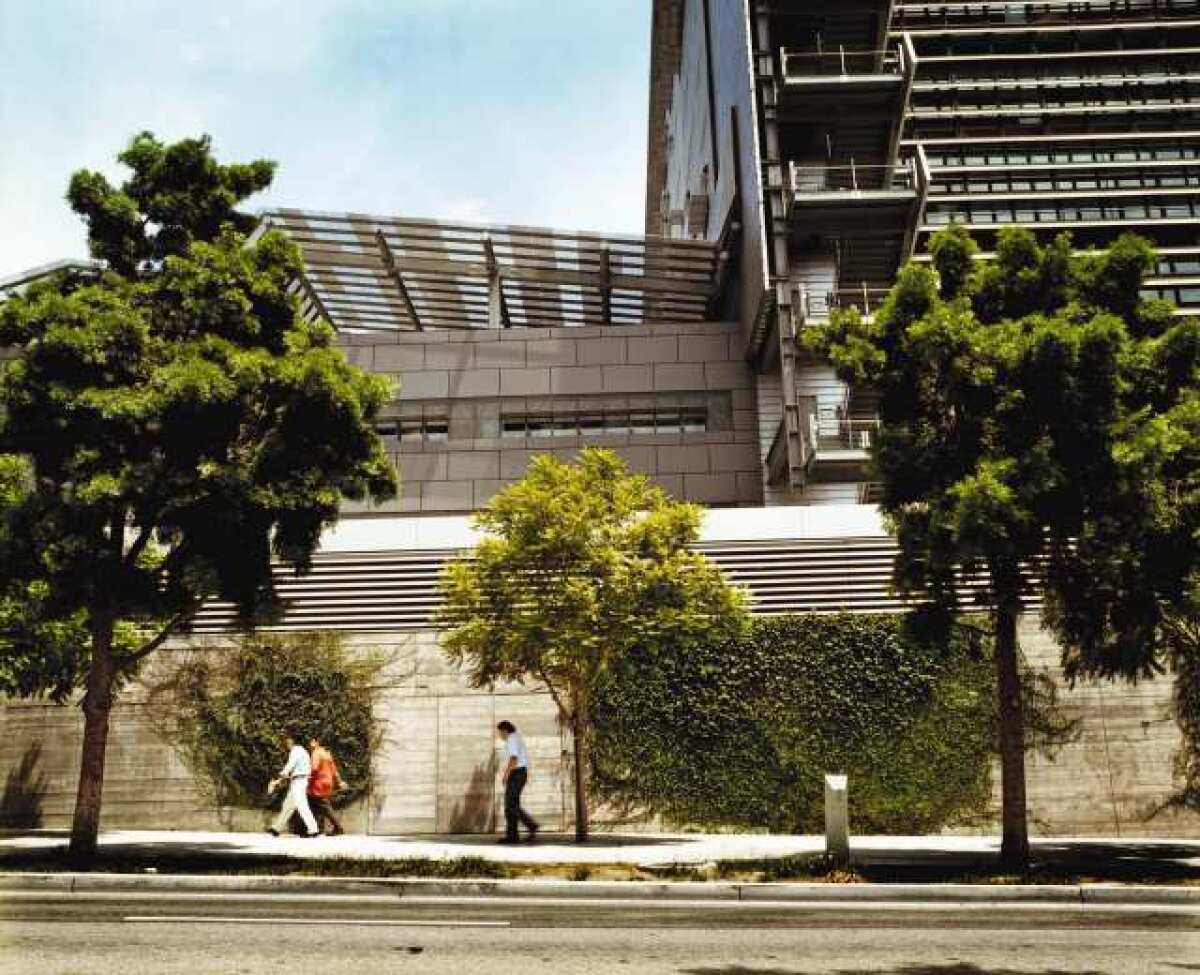

Where does that process start? As Gabel-Luddy will tell you, it starts with strategies to widen sidewalks and make sure that the architecture of new buildings enhances rather than deadens the streetscape. And trees--lots and lots of trees, such as the parallel rows of podocarpus and jacarandas that now are growing nicely on a stretch of 2nd Street along the southern edge of Thom Mayne’s 3-year-old Caltrans building. Thanks to landscape architect Douglas Campbell, that block is shaping up as one of the nicest to walk on in all of downtown L.A.; there is a pleasingly sharp contrast between the lush, symmetrical greenery and the hard-edged architecture of the building that looms above.

But the process also begins with an acknowledgment that real pedestrianism requires mass transit. And it’s here that the Urban Design Studio, no matter how enlightened its goals, runs up against a significant barrier: the region’s inability to put a full light-rail and subway system into place.

After all, most foot traffic--in cities as different as New York and Portland--goes hand in hand with a trip on a train or a bus. People walk or stroll most happily if they know they don’t have to walk or stroll all the way home. The massive immigration-rights protests last year were a product, if an extreme one, of the same equation. Only the Metro system made it possible for several hundred thousand people to march down Wilshire Boulevard and Broadway.

Whole sections of Los Angeles used to thrive because they were planned around that very idea. Anywhere you see a pedestrian path linking one street to another--they’re common in the hills of Echo Park and other neighborhoods--you know that a streetcar network once thrived nearby. Overgrown (with weeds or bougainvillea) and underused, the paths now look like the products of an archeological dig, the skeletal remains of a more walkable, and more humane, city.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.