The long and winding road

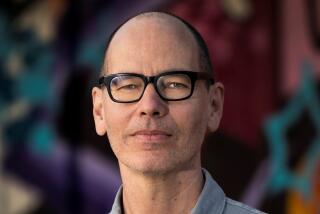

Hilburn worked with Michael Jackson during 1984 and early 1985 on a book Jackson is writing for Doubleday.

Michael Jackson’s $47.5-million purchase of the Beatles’ song collection last month was the climax of 10 months of intense, complicated and confusing on-again, off-again negotiations. The package--of which the Beatles music was only part of the nearly 4,000-song ATV Music catalogue--is believed to be the most expensive publishing purchase ever by an individual.

The maneuverings were filled with humorous sidelights and dramatic cliffhangers. And there were a lot of surprises. Negotiations became so snarled in May that Jackson’s representatives walked away from the talks and refused to return calls for nearly a month--even though they’d already spent more than $1 million and hundreds of hours in their quest to realize Jackson’s dream of owning the Beatles music.

Calendar pieced together a history of the negotiations through several sources. The normally secretive Jackson gave Calendar access to his advisers and negotiators. We also spoke with agents for the reclusive Robert Holmes a Court, the Australian tycoon who owns the songs.

Michael Jackson was in great spirits when Paul McCartney invited him to London a few years ago to work together on a record. He loves the Beatles’ music, especially such endearing McCartney melodies as “Yesterday” and “Eleanor Rigby.”

They spent several days at famed Abbey Road Studios, scene of legendary Beatles sessions, and came up with the lilting “Say, Say, Say,” which eventually went to No. 1 in the United States.

Jackson stayed at a hotel that, as irony would have it, was across the street from ATV Music, the publishing company that owned the Beatles catalogue of more than 200 songs. He would meet McCartney at Abbey Road around noon, and the two threw ideas back and forth while McCartney sat at the piano.

Jackson usually ate dinner at McCartney’s house, a Tudor-styled residence situated on nearly 1,000 acres an hour’s drive from the heart of London. Sometimes they would end up in the kitchen with McCartney’s wife, Linda, and their children--all helping to cook.

One night McCartney showed Jackson a thick, bound notebook filled with song titles. Jackson knew that McCartney had bought numerous song catalogues, including the works of Buddy Holly.

Jackson, never one to hide his emotions, became more excited as he turned the pages. He wanted to know more about owning songs: How do you buy them? What do you do with them after you have them?

The conversation moved on to other matters, but Jackson couldn’t get the song catalogues out of his head.

Soon after, Jackson met with his attorney, John Branca, in the den of the Jackson family home in Encino. They were supposed to talk about re-signing with BMI, the performance rights organization that collects songwriter fees for radio, TV and live performances. At the end of the meeting Jackson told Branca, “I want to buy some copyrights, like Paul.”

Over the next few months, Branca came up with lists of songs (copyrights) that were for sale. Jackson ended up buying the Sly Stone collection, which includes such pop-soul gems as “Everyday People” and “Everybody Is a Star.” He also purchased the Double Diamond package that features Len Barry’s “1-2-3,” and the Soul Survivors’ “Expressway to Your Heart,” songs Jackson has liked since his pre-teen days. Among other acquisitions were two Dion hits: “The Wanderer” and “Runaround Sue.”

Those purchases cost Jackson less than $1 million.

Branca realized that Jackson was ready for a larger move. He mentioned Combine Music, whose song catalogue includes many of the prized Kris Kristofferson hits (including “Help Me Make It Through the Night”) and Tony Joe White’s “Polk Salad Annie.” But Jackson passed. He only wanted songs that meant a lot to him, so he declined to bid on all but three of the 40 catalogues presented to him over the last three years.

By the beginning of 1984, Jackson was engulfed setting up the “Victory” tour. The matter of catalogues faded into the background--until his September meeting with Branca in Philadelphia.

Branca flew regularly on weekends during the lengthy “Victory” tour to meet with Jackson and the entertainer’s manager, Frank Dileo, about business details, ranging from merchandising to various tour disputes.

The sessions, held in Jackson’s hotel room after the concerts, frequently lasted two hours or more. Unlike pop stars who don’t enjoy business matters, Jackson is actively involved in all facets of his career because he knows how many artists have been ripped off financially and misguided artistically by outsiders.

At the end of the last year’s September meeting in Philadelphia, Branca had a surprise for Jackson. The attorney said casually, “By the way, the ATV catalogue is available.”

Jackson looked puzzled.

Branca added teasingly, “It includes a few things you might be interested in.”

“Like what?” Jackson asked.

“Northern Songs,” Branca replied.

Jackson recognized that name.

“You mean the Northern Songs?”

“Yeah, Mike . . . the Beatles.”

Jackson did a full turn, jumped in the air and shrieked. “But wait,” Branca warned. “Other people are also after the catalogue. It’s going to be a struggle.”

Jackson replied, “I don’t care. I want it . . . please.”

(Northern Songs, the publishing company that the Beatles established in the ‘60s, was bought in 1969 by Sir Lew Grade’s entertainment conglomerate, ATV. The Beatles music became the most glamorous--and valuable--part of the 4,000-song ATV Music Ltd. catalogue, which was later bought by Australian tycoon Robert Holmes a Court’s Bell Group.)

Looking back on the months of grueling negotiations that resulted in Jackson’s landmark publishing coup, attorney Branca shook his head a few days ago in his Century City office. The file on his desk reads simply, “Michael Jackson/ATV.” But he prefers the name his partner Gary Stiffelman came up with for the exasperating process: “The Long and Winding Road.”

The acquisition of ATV Music--believed to be the largest music catalogue purchase by an individual--illustrates the tensions and strategies of finance, show-biz style. One lesson: It’s a long way between the verbal and the dotted line. The Jackson camp thought it had a deal at several points, only to have new bidders enter the picture or find new and unexpected areas of debate.

Negotiations became so snarled with Holmes a Court last May that Jackson’s representatives walked away from talks, and refused, in effect, to even answer calls for nearly a month. This despite the fact that they had already invested more than $1 million in verifying the validity of ATV’s claims about earnings and song ownership.

The decision to walk away from the negotiations was but one of several key moves in a chess match as fascinating as it was frustrating.

For background: Why did the Beatles ever give up their publishing? And why didn’t McCartney buy the songs back himself?

John Lennon and McCartney faced major tax problems in Britain in the 1960s and to avoid paying 90% on earnings, they were advised to either sell their publishing rights outright or form a public corporation to deflect the tax burden. So, they established Northern Songs Ltd. as a public company with manager Brian Epstein and publisher Dick James.

The move made financial sense but it resulted in the Beatles losing the rights to the songs when ATV purchased the majority stock in Northern Songs. ATV’s music catalogue also included such early rock classics as Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti.”

One common misconception about the Beatles music is that McCartney and the Lennon Estate no longer collect on the songs. They, in fact, split the songwriting revenue with the publisher.

If, for instance, “Yesterday” earns $100,000 a year in royalties from record sales, airplay and live performances (it probably earns more), the Lennon estate and McCartney--as co-writers--divide about 50% of that income, around $25,000 each.

The publisher--now Michael Jackson--collects the other 50%. If Lennon and McCartney had retained their own publishing, they would receive the entire $100,000, though they’d have to pay someone to administer the publishing duties.

The publisher normally controls the use of the song in terms of films, commercials and stage productions. Just before the ATV catalogue was sold, for instance, Ford Motor Co. licensed the rights to “Help!” for a TV commercial.

If bought at a reasonable price and well administrated, catalogues are considered an excellent investment. They are such good investments, in fact, that it is increasingly difficult to find one on the market. The rule among today’s songwriters after the Beatles’ example: Never sell your publishing.

Explained Marshall Gelfand, Jackson’s accountant and business manager: “You’ve got to remember that when the Beatles started nobody in this business owned their own publishing. It wasn’t until the mid-’60s, when artists like Dylan and the Beatles started recording their own songs and selling millions of albums, that advisers began to understand the importance of holding onto your own publishing.

“The key thing to remember today is don’t sell your catalogue. The whole explosion of music videos and the trend toward using more music in movies is going to make copyrights even more valuable. If you are an established artist today, you should only consider selling your catalogue as a last resort to raise cash.”

So, why didn’t McCartney buy back the rights?

McCartney reportedly made offers to ATV over the years but--according to those close to the Jackson/ATV negotiations--he wasn’t a serious bidder in recent years. Among the competition for ATV’s rights: Charles Koppelman and Marty Bandier’s New York-based the Entertainment Co., London-based Virgin Records, New York real estate tycoon Samuel J. Lefrak and financier Charles Knapp.

A spokesman for McCartney said the ex-Beatle had no comment on the ATV acquisition, but an ATV representative--who asked not to be identified--speculated that McCartney wanted his own songs, but perhaps wasn’t willing to pay for thousands of other copyrights in the ATV catalogue. (The Beatles’ portion of the collection alone was estimated by one source to be worth about two-thirds of the purchase price.)

But McCartney was involved in an amusing sidelight: “Holmes a Court’s people were convinced for a while that Michael was a shill for Paul,” said a party to the negotiations.

“It seems Paul’s people once told one of the ATV officers that their client was interested in buying the copyrights, but that he didn’t want to go through lengthy negotiations. They said, in effect, ‘You go out and get your best offer and we’ll pay 10% more.’

“So, when Michael shows up, they know he is a friend of Paul’s and they suspect his bid is just a way for Paul to avoid paying the extra 10%. It took a long time to convince them that Michael was acting on his own.”

Jackson set out strictly to buy copyrights. But the package included buildings, a recording studio and some studio equipment--and a life insurance policy on his friend, McCartney McCartney.

Northern Songs had taken out insurance policies on all four of its principal owners, a common business practice. That means there was also a policy on John Lennon. Presumably, ATV collected on that in 1980.

Many pop fans may have been surprised when Jackson demonstrated the ambition and resources to pull off such a complex business deal. But the people close to the pop star were not surprised.

Frank Dileo, his personal manager, said he has long been impressed by Jackson’s “sound business sense. A lot of artists don’t want to know anything about business affairs, but Michael is involved in every facet of his career. He’s not one of those people who stops thinking when he walks out of the recording studio or off the stage.”

Jackson was just beginning to build his own team of advisers six years ago when he hired Branca. Until then, Jackson’s father, Joseph, had guided the affairs of all six brothers.

In Branca, Jackson found someone who was young (Branca’s now 34), easy to relate to and tough-minded. A native of Bronxville, N.Y., Branca was a law review editor at the UCLA Law School and represented such clients as the Howard Hughes heirs and the UCLA Foundation before joining the firm of Ziffren, Brittenham and Gullen in 1981.

By the time the “Thriller” album was released in late 1983, Branca had been out to Jackson’s house in Encino for so many meetings that he barely had to think about his driving.

He could concentrate on business matters as he departed from his office in Century City, drove west on Olympic Boulevard, then north on the San Diego Freeway, west on the Ventura Freeway, then the Hayvenhurst Avenue off-ramp.

The issue on his mind that afternoon in 1983 was copyrights. “Thriller” already was racing up the charts, showing every sign of becoming a blockbuster (it is now nearing the 40-million mark worldwide). That success meant CBS would have to renegotiate Jackson’s contract.

As in pro baseball, contracts are frequently torn up in the record business when an artist moves dramatically to a higher level of success. Double your home-run output to 50 and you get a new contract, even if you are bound by a 10-year agreement. Double your record sales to 10 million and it’s the same thing.

There is no legal obligation to sign a new contract, but companies want to keep their artists happy. As sales increase sharply, companies stand to make more money even if they pay a higher royalty.

After “Off the Wall” hit big in 1979, CBS increased Jackson’s royalty rate from around $1.10 per album to about $1.50 per album, according to industry sources. The new “Thriller” contract pushed that rate even higher, it has been reported.

Branca had more than royalty rates on his mind, however, as he turned into the Jackson driveway in late 1983 and waited for the iron gate to swing open. He and CBS Records president Walter Yetnikoff came up with a novel contract provision that would generate immediate cash for Jackson for the buying of catalogues. That was the start of Jackson’s copyright involvement.

Once Branca had Jackson’s go-ahead last fall on pursing the Beatles catalogue, he phoned Michael Stewart, the president of CBS Songs, one of the world’s three leading publishing firms.

Stewart, a 30-year publishing veteran, coordinated CBS’ purchase of the coveted MGM/UA song catalogue--a reported $65-million deal that included compositions from hundreds of movie musicals, including “Singin’ in the Rain” and “That’s Entertainment!”

In the ‘60s, Stewart was head of music for United Artists, a multifaceted position whose responsibilities included helping coordinate music for the company’s films. While at UA, ironically, he was involved in UA’s decision to take a chance on the Beatles, a then-unknown quantity in this country, and make a madcap movie called “A Hard Day’s Night.”

Stewart and UA also reportedly had the inside track on buying the rights to Lennon-McCartney songs in the ‘60s until the Beatles decided to form their own publishing company (Northern Songs) rather than sell their catalogue.

Branca called Stewart to discuss Jackson’s interest in the ATV copyrights. Stewart thought it was a great idea and remained an informal adviser throughout the negotiations.

“ATV is probably one of the 10 most valuable catalogues in the world, but the fact that it is the Beatles songs adds a whole other dimension to it,” Stewart said. “The Beatles catalogue was the beginning of a whole new world . . . socially, musically, theatrically.

“I thought it is very healthy for the music business for a star of Michael’s stature to say, in effect, ‘I believe in music and I want to invest my money in music, not real estate.’ I think it was a wonderful statement about his love for the Beatles and for music.”

One suspicion--not voiced by Branca--was that CBS was interested in the catalogue itself, but wouldn’t want to risk alienating Jackson by bidding against its biggest star. CBS had no comment on the matter.

At any rate, Branca’s first task was to determine the value of ATV’s music catalogue. Earlier offers for ATV reportedly ranged from $39 million to $60 million. But after meetings with Stewart, accountant Marshall Gelfand and others, Branca suggested an amount to Jackson: $46 million.

“Based on the earnings of the catalogue, we felt that was a fair price,” Branca explained. “Catalogues usually bring five to seven times the annual net publisher’s share. We knew someone had bid $39 million and we wanted to be above the crowd, but not so high that we didn’t have room to go up.”

Jackson agreed to move forward.

On Nov. 20, he communicated the $46-million bid in a Telex to ATV’s owner, Holmes a Court, requesting a meeting be held within 10 days in London.

Robert Holmes a Court was characterized in a recent Fortune magazine profile as “Australia’s acquisitive recluse--a corporate hunter with a $1-billion war chest who has gobbled up companies at home and in Britain and is now stalking the U.S.”

Holmes a Court, 48, was born in South Africa but moved to New Zealand in his teens and then on to Australia where he studied law. He then moved into the high-finance world of corporate takeovers.

He has been generally described as a cool, skillful and shrewd strategist. A recent New York Times report suggested his success has “largely been the result of skillful planning and audacity. He has also been grossly underestimated by the targets of his takeover bids.

“Because he has so often pulled out of a bid midway, nearly always taking a large capital gain, those on the receiving end never know whether he is serious or not,” the article stated.

He was definitely serious in 1981 in his successful takeover of Lord Lew Grade’s financially troubled entertainment conglomerate, which included London theaters, several movies (including “On Golden Pond”)--and the Beatles songs.

Holmes a Court maintains a low profile and his representatives said he wouldn’t be available to be interviewed for this article. Some of his representatives, however, did agree to provide background on the negotiations as long as they not be quoted.

One aide said that Holmes a Court put his ATV Music on the market last fall after legal difficulties with McCartney were resolved. “It was not like we wanted to ‘dump’ the catalogue, but we wanted to test the market,” he added.

Holmes a Court acknowledged receipt of Jackson’s $46 million offer and scheduled a Dec. 14 meeting in London.

Branca, who would only personally attend meetings when Holmes a Court was present, was represented by David Gullen and Gary Stiffelman, also with the firm of Ziffren, Brittenham and Gullen, at these sessions. Holmes a Court was represented by Geoffrey Davies, a London attorney, and Alan Newman, a key executive.

The Jackson team’s objective in the meetings in the ATV headquarters in London was to get a letter of agreement so that they could undertake the massive task of verifying ATV’s legal and financial reports.

Stiffelman, who estimated he spent 900 hours on the purchase between Dec. 14 and Aug. 10, realized that the negotiations were going to be extremely complex. One reason: ATV had already devised a method for the sale that involved restructuring the company into several subcompanies.

This seemed in keeping with Holmes a Court’s reputation as a difficult man to deal with.

In the Fortune profile, Holmes a Court expressed amusement at American reaction to what was described as his patient, somewhat unorthodox strategy: “They’re just looking for me to play according to their rules and make it a big game. The Viet Cong didn’t play by the rules, and look what happened.”

Jackson’s attorneys wanted a binding agreement so that Jackson would be assured of the catalogue if an examination of books and documents confirmed ATV’s statements about income and copyright ownership. But the company didn’t want to commit itself unless Jackson agreed to virtually take the catalogue “as is”--or regardless of findings.

The two sides finally compromised on a short memorandum that didn’t bind either party, but suggested mutual interest. The Jackson group then began to check ATV’s books. The process took four months.

One team of Jackson’s lawyers was sent to the United States Copyright Office in Washington to check on the authenticity of every significant composition in the nearly 4,000-song catalogue. Meanwhile, other teams were at work in London and at ATV offices around the world to certify legal documents in those countries. In total, an estimated half a million to a million pages of contracts were examined.

At the same time, the L.A.-based accounting firm of Gelfand, Rennert & Feldman was overseeing a team of 20 people who were checking ATV books in London, Los Angeles, Toronto, Sydney, Munich and Amsterdam.

The examination came up with a few discrepancies but not enough to kill Jackson’s interest. Last April, the Jackson team was ready to proceed.

Branca looks back as crucial the decision to conduct the legal and financial audit despite the absence of a binding contract.

The research was essential because you can’t just assume all the papers and copyrights are in order even though ATV has been involved with them for years. What if it turned out that Lennon and McCartney signed a contract that gave away rights after, say 30 years to several key songs? Among other issues that had to be explored: What would happen under American law if Yoko (Ono) filed suit over John Lennon’s royalties?

“The danger in taking the time to check on all these matters was that Holmes a Court could have changed his mind and not sold the catalogue, or have sold it to another party,” Branca acknowledged. “But we figured that anybody who bought the catalogue would have to go through the same checks and we’d be three months ahead.”

While the studies were being conducted, Stiffelman continued to meet in London with ATV representatives. They began sketching contracts in January and then sat down March 16 for a series of follow-through meetings that lasted weeks. The parties went through eight drafts of the contract.

If the sessions sometimes seemed like a battlefield, the parties could appreciate the irony that the meetings were held in the very room that French Gen. Charles de Gaulle used as his London headquarters during the German occupation of France in World War II.

Things moved slowly, according to the Jackson team, as parties debated endlessly on the issues of price, warranties and the complicated structure of the deal.

Then, Michael, the pop star, helped his own cause. While in London last March to see his wax figure unveiled at Madame Tussaud’s, he dropped in on the dreary meetings--and brightened everyone’s mood.

“It’s a lot more fun selling something to a superstar than a corporation and the visit reminded everyone that they were dealing with a superstar,” Stiffelman said. “Michael showed up in his whole, colorful Sgt. Pepper’s uniform--and he signed autographs for all the office workers. He was very impressive and he definitely helped get things moving.”

By April, it was time for Branca and Holmes a Court to finally meet face to face. Agreement at last?

Not quite.

When they met in New York, Holmes a Court had already reviewed the contract and found various provisions unacceptable. The promise of a quick settlement faded rapidly. Frustrated, Branca concluded that Holmes a Court was not even close to making the deal final.

The attorney phoned Jackson at home in Encino to say he felt it was time to tell Holmes a Court that either the parties should come to an immediate agreement or that Jackson should withdraw his offer.

Jackson reportedly agreed to the hard line, yet the star was clearly anxious about losing his prized Beatles songs. He already had gathered every book he could find on the Beatles and had read all about his favorite Lennon-McCartney songs.

Branca went back to the meeting with Holmes a Court, expressed Jackson’s impatience--and the two shook hands on the terms of a deal. They agreed that Stiffelman would go to London to meet with Holmes a Court to go over what were presumed to be minor details.

For Stiffelman, that London meeting was the low point of all these months. Several issues, which the Jackson team thought had been resolved, were re-introduced. One demand, which Holmes a Court apparently made of all bidders, was that the Australian be allowed to keep a few ATV songs as gifts to relatives or friends.

Stiffelman returned to Los Angeles.

The deal was in jeopardy.

Jackson’s team tends to describe the extended ATV bargaining talks as grueling and frustrating. They complain about what they described as frequent shifts of positions by the Holmes a Court unit. But the other side suggested the process was simply “business as usual,” arguing that the refusal of Jackson to meet personally with Holmes a Court added to the complications: “If it was ‘tough and frustrating,’ that’s one reason why,” one source said.

Another Holmes a Court rep likened the whole affair to “a game of poker,” complete with a series of bluffs and counterbluffs that almost saw the deal unravel:

In Encino, Branca told Jackson that it was time to be tough--to tell Holmes a Court that he had to either accept their last offer or the whole deal was off. Jackson agreed and Holmes a Court got the message.

But the Australian played it cool. He sent Branca a letter in May noting that the negotiations had gotten off course and offered to reopen the door. He said he would view Jackson as the exclusive bidder for 30 days, but would entertain other bidders after that.

Branca ignored the letter for three weeks. Just before the deadline, he sent Holmes a Court a letter that essentially said that Jackson had made his final offer. If it wasn’t accepted, he wished Holmes a Court good luck with other bidders.

In early June, Holmes a Court informed Branca in another letter that Jackson’s exclusive had expired, though he still welcomed Jackson’s interest.

The Jackson team, which had been interpreting Holmes a Court’s letters as signs that he still viewed Jackson as the chief bidder, got a jolt a few days later. They learned that Holmes a Court had signed a tentative $50-million deal with Charles Koppelman and Marty Bandier’s Entertainment Co.

But in early August, Holmes a Court’s agents contacted Jackson again, saying the door might still be open. Branca informed Holmes a Court attorney Geoffrey Davies that Jackson was indeed still interested, but only if something could be concluded quickly because Jackson was considering another major investment.

Holmes a Court exec Alan Newman called back to invite Branca to London. Branca then learned that Koppelman was also going to meet with Holmes a Court. It set up what had all the earmarks of an old-fashioned showdown.

In London, however, the shoot-out never materialized. Branca and Stiffelman sensed that Holmes a Court was finally ready to make a deal--with Jackson.

During this frantic period, concessions apparently were made by both sides. Jackson agreed to up his offer by $1.5 million. Holmes a Court threw in some other assets and also agreed to set up a scholarship in Jackson’s name at a U.S. university.

Though Koppelman had actually come up with a higher bid, Holmes a Court apparently accepted Jackson’s offer because it appeared that the singer could close the deal more quickly. Jackson’s early decision to examine the books before waiting for a formal contract turned out to be the key to the deal, a Holmes a Court representative said recently.

“In the end,” he suggested, “it came down to who could act fastest . . . and Mr. Jackson was in a position to act.”

Had the Holmes a Court team been worried when Jackson broke off negotiations?

“We never felt we were in the position where we had to sell the ATV catalogue,” one Holmes a Court aide said. “It’s a wonderful catalogue with marvelous songs, so we could have kept it unless we got the right terms.”

Why sell the catalogue in the first place?

“Cash is nice to have, too.”

The contract was finally signed at 2:45 a.m. on Aug. 10, though neither Jackson nor Holmes a Court was present. The two will meet for the first time next month when Jackson visits Australia as the guest of Holmes a Court. The visit won’t just be a courtesy call. It’s a contract provision requested by Holmes a Court.

Jackson talked excitedly about the Beatles songs as he sat a few days ago in his upstairs bedroom at the family house in Encino. The tension of the acquisition was far behind him.

“The melodies,” he said, enthusiastically. “They are so lovely . . . (and) structured so perfectly.”

Jackson dislikes being quoted, but he couldn’t resist agreeing to nominate his five favorite Beatles songs.

Asked if he wanted to look at a list of the songs to refresh his memory, he shook his head.

” Yesterday ,” he said with a conviction that suggested it was far and away his favorite.

He continued:

“ ‘Here, There and Everywhere.’

“ ‘Fool on the Hill.’

“ ‘Let It Be.’

“ ‘Hey Jude.’

“ ‘Eleanor Rigby.’

“And ‘Penny Lane.’

“ ‘Strawberry Fields Forever.’

“And. . . .”

He realized that the list had stretched beyond five.

“Can I make it my favorite 10?”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.