The art of public correspondence

I’ve been thinking about letters lately, keyed by a couple of intriguing projects: Alexander Chee’s “Dear Reader” collaboration with the Ace Hotel New York and Darcey Steinke’s blog-based “Letter Project.” Both approach correspondence through the lens of art, making what is inherently a private form of communication public, while still insisting on a vivid intimacy.

What is a letter, after all, if not -- as Steinke suggests in an email -- “a piece of writing directed at a single soul”? Still, what does it mean to share that (or aspire to) with a wider audience?

The “Dear Reader” project addresses this question in general terms, featuring 12 writers, one a month for a year, who will spend a night at the Ace and write a kind of open letter inspired by the experience, to be numbered and distributed to guest rooms in an edition of 300. (The first, by novelist Atticus Lish, was scheduled to go out this week.)

Steinke, meanwhile, is sharing a single correspondence, with her friend Nora O’Connor, a writer and professor, as it unfolds in time.

This is not the first time Steinke has made such a back-and-forth public; last summer, she posted a series of letters between herself and the writer Kevin St. John. The process can be tricky; “I know after we were done and we talked about it,” she acknowledges, “Kevin said that sometimes he could not write the things he wanted to about his life, not because he did not want to share them with me but that he did not want a larger audience to see it. And I honestly felt the same.”

That’s a fascinating tension, one that exposes the seams between writing for a readership and writing for ourselves. Letters are, by their nature, a bit of both -- directed outward, toward a recipient, but also revealing in an offhand way.

When I used to write letters (I don’t much anymore), I relied on them as a warm-up to begin the writing day. Steinke describes a similar experience: “Somehow writing to one person who had specific ideas and themes and questions helped me both figure out my own ideas and also connect with them more deeply. Before I started to work on my novels each day I used to write a letter. It was maybe how an artist sketches first a little before they jump into their work.”

At the same time, each letter exists as a work, or an expression, in its own right, a kind of mental and emotional snapshot of where we are right now.

Steinke’s opening missive to O’Connor is a case in point, a report from a monastery where she is on retreat. It begins with a consideration of Mary Baker Eddy (there’s a name you don’t hear every day) before recalling an instance of headache and confusion that leaves her worried about the delicacy of the brain.

Eddy was afflicted with her own ailments; she was, Steinke tells us, “bed ridden, depressive, as so many women were at that time.” This suggests a subtle confluence, conversational and focused at once.

We are, after all, always thinking, always tracing lines between us, always seeking to make a kind of sense. This is what letters encourage, a way of ruminating out loud on paper about the ordinary experience of our days.

“With letters,” Steinke observes, “I feel I am unfurling myself, and it’s very freeing. Also when I write a letter I always come away feeling more confident. Like, look I read that book this week and I had a few good ideas on it and maybe I didn’t handle that fight with my husband as badly as I thought I did. Or at least I can see now where I was wrong.”

Yes, and one other thing also, which is why, I want to say, we may be seeing a renewed engagement with the letter again. We live in a moment defined by speed, by connectivity rather than connection, in which, for all that we claim to be together, we end up, too often, alone.

A study last summer of loneliness in Britain reminds us that electronic communication can be both “a boon and a problem ... beneficial when they enable us to communicate with distant loved ones, but not when they replace face-to-face contact.”

This is so obvious as hardly to need repeating, and yet, what do we do to correct the trend?

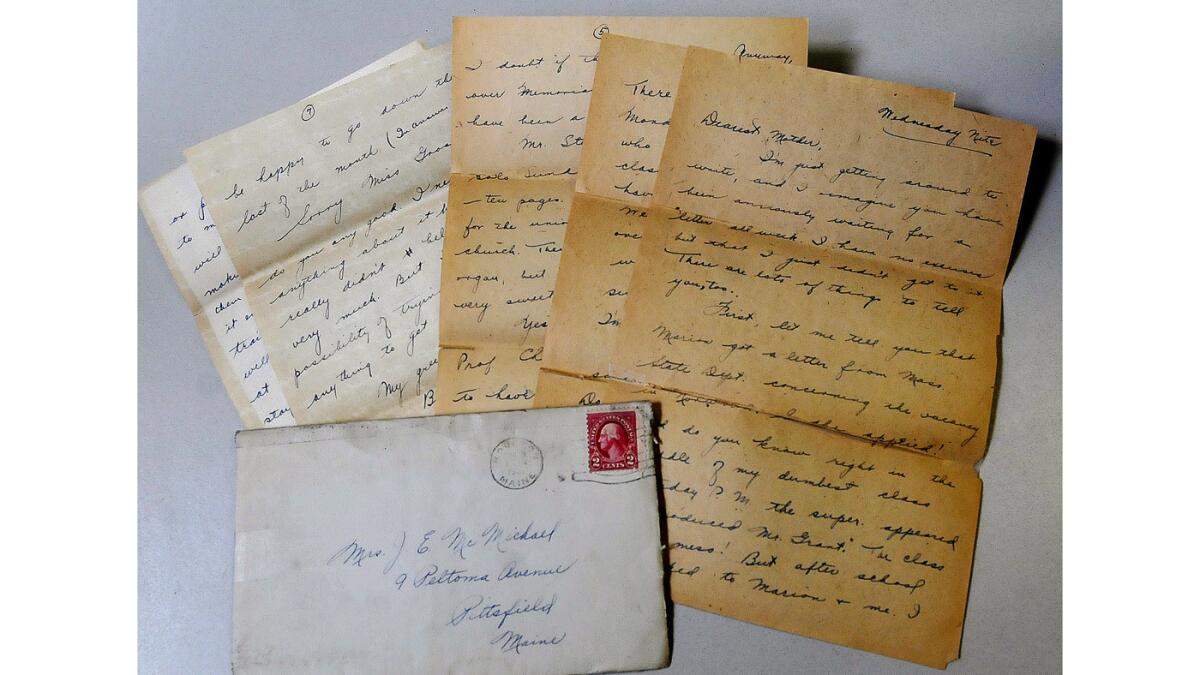

One answer may be to address each other one to one, with urgency and consideration, about the things that matter: love, loss, longing, family, our doubts and our desires. This is what letters do, what they have always done, whether they are shared in public projects or sent silently through the mail.

In that sense, they offer a way for us to slow down, to reflect on what’s important, in our lives and in the lives of those we love.

“I’d argue,” Steinke insists, “that letters are the most human form, the freest, the most radically intimate. And if I have to do projects to keep writing them I will.”

Twitter: @davidulin

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.