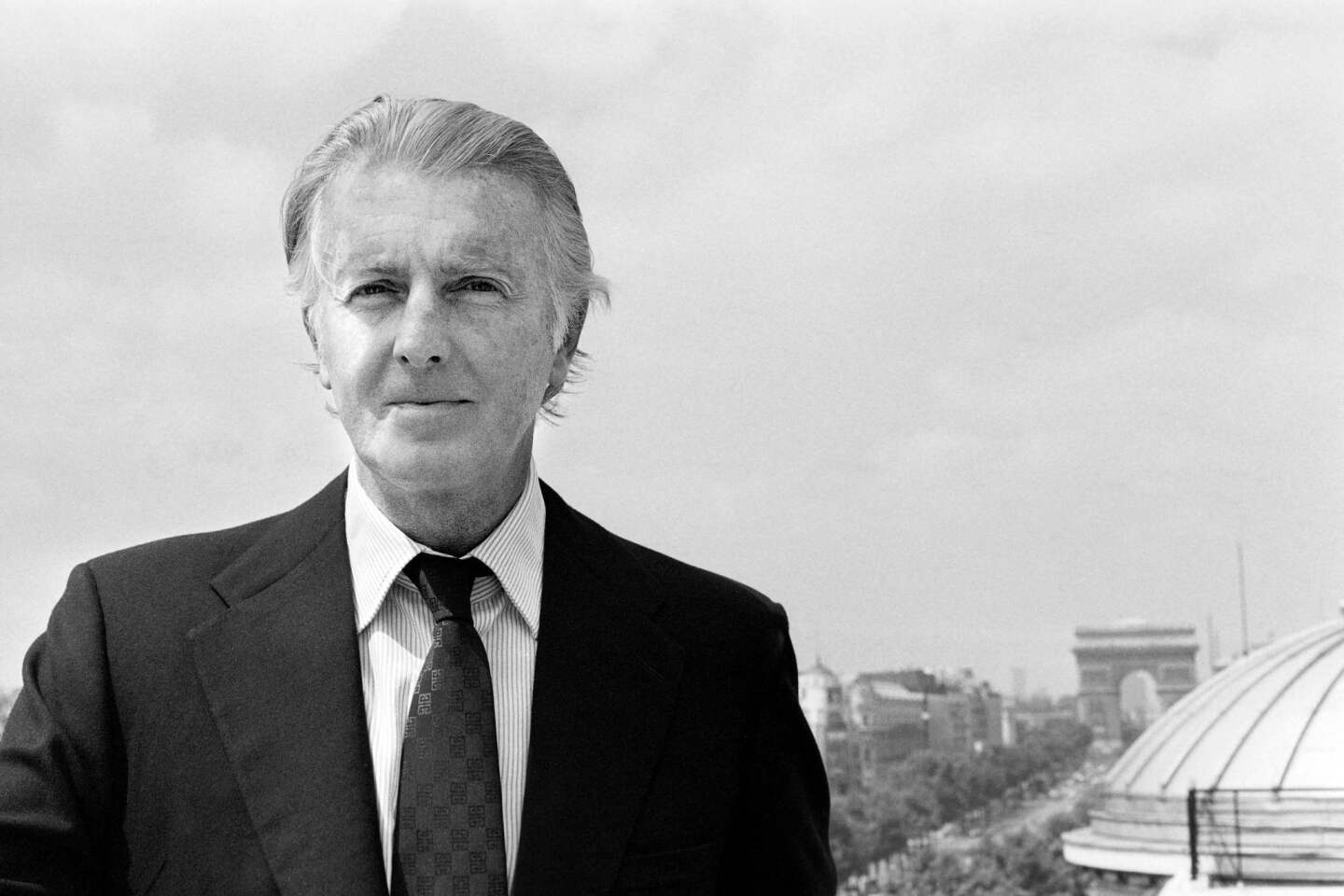

Hubert de Givenchy dies at 91; courtly designer dressed Audrey Hepburn, built fashion empire

Hubert de Givenchy, the elegant designer who dressed Audrey Hepburn for seven of her movies and once shipped a black dress overnight to Jacqueline Kennedy when she requested it for the funeral of her husband, has died, the fashion house announced Monday. He was 91.

The house of Givenchy paid homage to its founder in a statement, calling him “a major personality of the world of French haute couture and a gentleman who symbolized Parisian chic and elegance for more than half a century.”

For the record:

4:00 p.m. March 13, 2018An earlier version of this article said Hubert de Givenchy had won an Oscar for costume design for his contributions to “Sabrina.” The Oscar for costume design for “Sabrina” was awarded to Edith Head.

“He revolutionized international fashion with the timelessly stylish looks he created for Audrey Hepburn, his great friend and muse for over 40 years,” the house of Givenchy said. “His work remains as relevant today as it was then.”

Claire Waight Keller, who has been at the helm of the brand since last year, said on her official Instagram account she is “deeply saddened by the loss of a great man and artist I have had the honor to meet.”

“Not only was he one of the most influential fashion figures of our time, whose legacy still influences modern day dressing, but he also was one of the chicest most charming men I have ever met,” she wrote.

Bernard Arnault, CEO of LVMH, which bought the brand in 1988, said he is “deeply saddened” by Givenchy’s death.

“He was among those designers who placed Paris firmly at the heart of world fashion post-1950 while creating a unique personality for his own fashion label,” according to a statement released by LVMH.

One of the first French fashion designers to create an international empire under his signature, Givenchy had a statuesque physique, perfect grooming and Old World manners. He lent refinement to the roughhouse world of fashion. He could make a courtly bow or the kiss of a woman’s hand seem perfectly natural.

At work in his Paris atelier, “Monsieur,” as his staff addressed him, wore a white lab coat, the French couturier’s uniform but from the time he opened his business in 1952 he followed his own fashion formula. At the core of a woman’s wardrobe, he placed a sheath dress — a column of subtle curves that became the basic item for many socially prominent women through the 1960s.

Before his business was 10 years old Givenchy had made his mark with dresses that were destined to become icons of their era in part because Audrey Hepburn, Givenchy’s close friend, wore them in her movies. An embroidered white organdy dance dress Hepburn wore in “Sabrina” (1954) and the sleeveless column dress she made famous in “Breakfast At Tiffany’s” (1961) became international fashion symbols of Givenchy’s clean, fresh glamour.

“Givenchy was the quintessence of post-World War II French couture,” said fashion historian Valerie Steele, director of the museum at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology. “His clothes were very elegant and intended to make women look beautiful. He is best known for his designs of the ’50s and early ’60s for Audrey Hepburn.”

He met Hepburn in 1953 when she visited his Paris atelier to ask about wearing his designs for “Sabrina.” He agreed to meet with her only because he thought the other Miss Hepburn, Katharine, was calling.

“Immediately we had this great sympathy together,” Givenchy told the Los Angeles Times in 1995 of the first time he met Audrey Hepburn. “She was a dancer and she knew perfectly how to walk and move. I remember how beautiful I thought her smile was.” From then on he designed his collections as if they were with Hepburn in mind.

She invited him to Hollywood in 1963 during the filming of “My Fair Lady” to give him a close look at the period-piece costumes that won Cecil Beaton an Academy Award in that picture. She referred to Givenchy as “my beautiful Hubert.” He marveled at her devotion, especially as she became more famous. “Her loyalty was fantastic,” he told The Times in 1995. “She helped me tremendously in my work.”

Most of the outfits Hepburn wore on screen were from the ready to wear collections sold in a rising number of Givenchy boutiques, which made it possible for any woman with the means to dress like her. By the late 1960s Givenchy’s label was carried in 10 American retail stores, including Bullocks Wilshire in Los Angeles, where he arrived at the opening in 1969 dressed in a red trench coat over navy blue slacks, shirt and loafers.

In every city where he did business, Givenchy got to know his best customers. As a bachelor who traveled alone, he was the perfect dinner partner.

“Givenchy understood the lifestyle of his key customers,” said Rose Marie Bravo, formerly an executive of Saks Fifth Avenue, which carried the Givenchy label. “He observed how they lived and designed clothes that complemented their lives.”

“Monsieur Givenchy knew how to make a woman look beautiful and alluring,” she said. “He exuded class. If he did something a certain way it had instant credibility.”

His social ease made him an effortless pioneer of the “lifestyle” marketing that caught hold in the 1970s. “He was one of the first to develop his image not only by his fashion sense but by his impeccable manners and by the chic he brought to all that he touched,” Bravo said.

His chateau in the Loire Valley, his Paris apartment, his rose gardens and Louis XIV antiques, the black Labrador retrievers that trotted beside him at home, helped sell his image. He invited the press to his home and showed them around. They reciprocated with full-page color magazine layouts.

“He lived very grandly,” said Jody Donohue, Givenchy’s New York press agent during the 1990s. “He was the first person I ever met who had a separate, summer wardrobe for his furniture. He covered everything in white duck cloth.”

As a designer he had a gift for putting his own touch on other peoples’ best ideas. He made no secret of his debt to his mentor, Cristobal Balenciaga, the Spanish designer who settled in Paris and set trends in the 1950s with his clean lines and sparse adornments.

“Givenchy saw Balenciaga as his master,” said Steele. “But while Balenciaga was a profound, artistic designer who could be more extreme in his designs, Givenchy was never as stark or severe.”

Givenchy met Balenciaga soon after he opened his own atelier in 1952. Over the years, a number of Givenchy’s designs were so similar to Balenciaga’s that he was seen by some as a copycat.

Balenciaga didn’t seem to mind. When he closed his couture house in 1968, he escorted several of his best customers across the street to Givenchy’s salon and personally made the introductions.

At an early point in his fashion career Givenchy borrowed from women’s sportswear, an American invention, for his collections. His “separates” — a skirt, blouse and cardigan sweater for day, and a two-piece evening gown — notched up the sophistication level of the American innovation.

The old seemed fresh and new in his hands. If he added embroidery work to a dress, it was as much a reference to a Givenchy family trade as it was a fashion novelty. His grandfather had been the manager of the famed Beauvais tapestry works.

Born in Beauvais, France, on Feb. 21, 1927, the son of a marquis, Givenchy’s favorite boyhood memories included time spent with his grandfather’s collection of rare textiles. “I’d look at them and touch them for hours,” he told People magazine in January 1996. “I think that is where my vocation began.”

His parents chose law as his profession and Givenchy attended the University of Paris. But at age 17, with a few of his design sketches to show, he visited couture houses in Paris looking for work.

His first call was at the atelier of Balenciaga, already his idol, but he was turned away at the door. He had better luck at the atelier of Jacque Fath, who gave Givenchy his first job in couture. He later worked as an assistant designer for Elsa Schiaparelli. He was 24 when he showed his first solo collection. He had known he wanted to be a designer from the time he was 6.

Three years after he opened his own business, he designed a low-priced sportswear collection for young women, a break from the conventional couture designer’s approach to business. The mass-produced sportswear line was produced by a U.S. manufacturer and sold in U.S. department stores. Glamour magazine showed a sweater from the first line on the cover of the December 1955 issue. “Young chic,” the caption declared. “For when they want to look casual in a worldly way.”

It was his first step toward the licensing agreements with manufacturers that expanded his empire to global reach by the mid-1970s. Givenchy’s signature adorned shoes, belts, sunglasses, purses, a menswear collection and other items. Licensing agreements pushed his annual sales to more than $100 million.

That and a fragrance division that was headed by Givenchy’s brother, Jean Claude, his only sibling, until Jean Claude retired in 1987, made the designer a multimillionaire. But just as his business peaked, fashion trends were turning in a new direction. More adventurous designers experimented with lighter construction, more relaxed shapes and new, more flexible fabrics. Givenchy stayed his course and suffered for it.

Before he sold his business in 1988, he told friends he was losing money. The French luxury goods conglomerate, LVMH (Louis Vuitton Moet Hennessey) bought him out, with the rights to his name, for $46 million. He continued for close to 10 years as the chief designer.

Givenchy’s association with Hepburn kept his name in the news. She presented an Oscar at the 1992 Academy Awards wearing a deep pink Givenchy gown that showed off her wraithlike figure. Hepburn’s streamlined glamour was a potent reminder of the extraordinary influence she and Givenchy had on style during their 40 years together.

In April 1993, several months after Hepburn died of cancer, Givenchy created a small collection of 20 cocktail and evening dresses for Barneys, the New York specialty store, inspired by the “Audrey” look of the ’50s and early ’60s. The collection did well and several more followed.

Los Angeles businesswoman Rosa Nava opened the Givenchy Hotel and Spa in Palm Springs in 1995, modeled on the original Givenchy spa at Versailles, near Paris. She owned the operation and Givenchy sold his name to the project and designed several of the staff uniforms. “I tried to maintain Hubert de Givenchy’s understated elegance,” Nava told The Times in 2003. Two years later she sold the spa and Givenchy’s name was removed.

In 1995, after rumors that the new owners of the Givenchy fashion empire wanted a younger image for the label, British designer John Galliano was hired for the job — a trendsetter half Givenchy’s age.

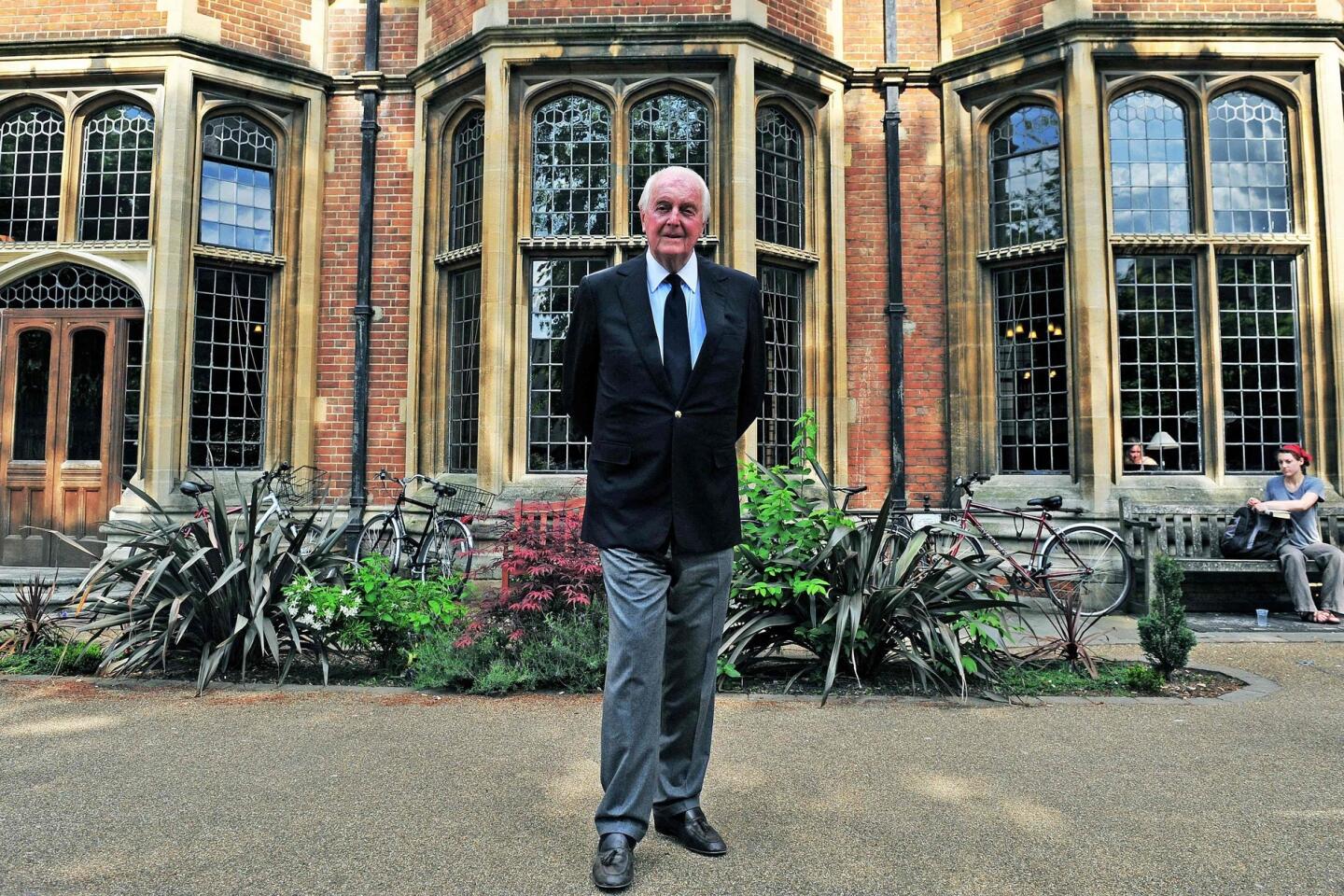

The dignified, ever-correct Givenchy learned the name of his successor when it was announced after one of his last fashion shows. He was shocked, gracious and uncomplaining during the press interviews that followed. “You have to know when to stop; that is wisdom,” he told Time magazine in 1996. Privately, he told friends he had been forced out.

At his final sendoff in 1996, he stepped onto the fashion runway to take a bow. Sean Ferrer, Audrey Hepburn’s son, presented him with flowers from the 60 rose bushes Givenchy gave her on her 60th birthday. Only then did his eyes fill with tears.

The house of Givenchy went through several creative directors in the 10 years after Givenchy retired. In the fall of 2005, the house did not produce an haute couture fashion show for the first time in 53 years. None of the young designers who were offered the job accepted it. To be chief designer of a couture house no longer seemed like a risk-free opportunity. The new attitude reflected the fact that the French couture business was in decline.

After he retired, Givenchy was more outspoken than usual. “Fashion today is ugly,” he said in an interview with People magazine in January 1996. “There’s no elegance to it. No one is discreet.”

At the same time he said he had no regrets for making a career of it. “To have lived your dream is very rare in life,” he said. “I have been so fortunate.”

Rourke is a former Times staff writer

The Associated Press contributed to this article.

UPDATES:

7:25 a.m.: This article was updated with a statement from the house of Givenchy, and reaction from figures in the fashion world.

The article was originally published at 7 a.m.