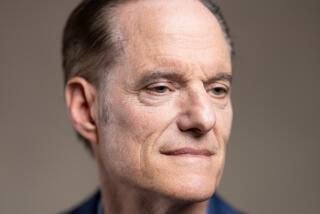

Mathilde Krim, who galvanized worldwide support in the fight against AIDS, dies at 91

Mathilde Krim’s rise to prominence as an AIDS researcher and global crusader in the early fight against the deadly disease began with a simple phone call from a friend.

A physician in New York’s Greenwich Village, Joseph Sonnabend, told the scientist about the strangely similar symptoms in many of his gay male patients — swollen lymph glands, enlarged spleens, stubborn infections. Their immune systems were hopelessly compromised.

Within months, all of the affected patients had died.

“It was totally mind-blowing for a scientist who thinks she knows something to realize that, here in the middle of New York in the 20th century, a new disease could occur,” Krim told the Los Angeles Times in a 2000 interview.

Bearing witness to the early ravages of the mysterious syndrome, the geneticist and virologist threw herself into the fight against AIDS and emerged a fierce crusader for showing compassion and empathy for those whose lives were touched by the disease.

A lifelong activist who was shaped first by the Holocaust and then the AIDS epidemic, Krim died Monday at her home in Kings Point, N.Y.. She was 91.

“Mathilde Krim exemplified the notion that a single person can change the world,” tweeted Elton John, who worked alongside Krim to raise funds for AIDS research. “She committed the entirety of her life to finding a cure and treatment for HIV.”

Robert Frost, the chief executive for the Foundation for AIDS Research, or amfAR, said although he was gripped with a “penetrating sadness,” he was heartened by the sheer scope of Krim’s life work.

“There is joy to be found in knowing that so many people alive today literally owe their lives to this great woman.”

Born in Como, Italy, on July 9, 1926, Krim grew up in Switzerland. Though initially shielded from the atrocities of World War II, Krim was forever touched by newsreels that showed the liberation of Nazi death camps and the skeletal figures who emerged.

“I confronted the reality that racism is murderous,” she told The Times. “I learned a lesson there.”

Appalled, she joined a Zionist underground movement and helped smuggle guns across the Swiss-French border for its members. She also pursued a career as a scientist, eventually earning a doctorate in genetics at the University of Geneva.

After marrying a medical student, Krim told her parents she was converting to Judaism and moving to Israel. She said her parents, who she’d long suspected were at least mildly anti-Semitic, were horrified.

The marriage ended in divorce, and Krim moved to New York several years later after marrying Arthur Krim, chairman of United Artists. Mathilde Krim initially accepted a position at Cornell Medical School to study cancer viruses and then became a researcher at the Sloan Kettering Institute for Cancer Research in New York.

Both fascinated and horrified by the mysterious virus that was taking a heavy a toll on gay communities across America, Krim sought to both understand the disease and raise funds for better and quicker research. She quickly saw what a lonely fight it would be.

When Krim tried to rally scientists, corporate donors and government officials, most turned away. Time and again people told her the disease was striking “those who deserved it.”

“In those early days, they were literally dying in the streets,” Krim said. “[Gay men who had AIDS] lost their jobs, their apartments — their families turned away from them. It turned my stomach. It really impacted me, and I decided this was something not to be tolerated.”

She watched angrily, helplessly as AIDS started showing up in other populations: hemophiliacs, intravenous drug users, blood transfusion recipients and newborns.

Still, the public and many government officials seemed surprisingly unconcerned. In 1983, Krim took matters into her own hands. She established the AIDS Medical Foundation to serve as a “scientific venture capitalist.”

It would provide seed money to researchers with innovative AIDS-related theories and technologies — scientists who, in many cases, had been turned down for funding by government agencies. She also hoped her organization could educate the public about the disease and would effectively lobby for legal protection of the afflicted.

Arthur Krim tendered the organization’s first capital: about $100,000. Within 90 days, Mathilde Krim raised $550,000 more.

Soon, a growing number of researchers turned to her organization for funding. Krim began putting in 16- to 18-hour workdays, seven days a week, to oversee operations; visit hospices, clinics and adult daycare centers; keep current with scientific literature; and host fundraisers.

One of her earlier backers — and a co-founder of amfAR — was actress Elizabeth Taylor.

“Elizabeth Taylor got AIDS [talked about] on ‘Entertainment Tonight,’ and you can’t underestimate the value of that kind of exposure,” said Randy Shilts, who wrote the landmark chronicle “And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic.” “It made the disease something that respectable people could talk about.”

In 2000, Krim was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the U.S.

Krim is survived by a daughter, Daphna; two grandchildren, Robert and Amanda; and a sister, Maria Jonzier.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.