As number of transfers in high school sports grow, so do ripple effects

Each second that ticked off the clock, each minute that slipped past, ate away at him.

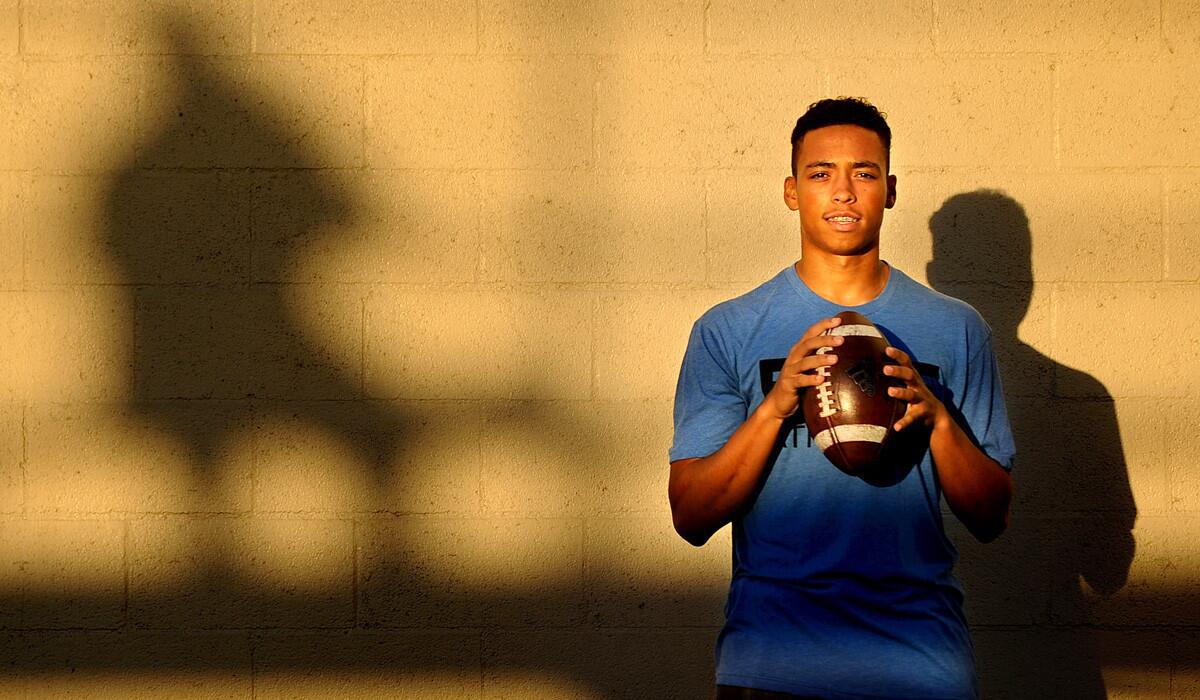

The kid may have looked young with a slight build and boyish features, but his rifle arm made him antsy to play quarterback at Oaks Christian High.

As a freshman, Malik Henry was expected to wait another season or two behind the older players. He was supposed to watch from the sideline in a spotless uniform.

“I was really frustrated,” he said. “I wanted to get on the field.”

Ten years ago, Malik would have been stuck. Like other talented underclassmen, he would have continued champing at the bit, gaining experience and toughness in practice, gradually maturing until his turn came along.

But times have changed, and so have the rules governing California high school sports, which now allow athletes to jump from school to school with little or no penalty.

“I can’t just sit back and watch,” Malik told his father.

A few minutes down the road in Westlake Village, the starting quarterback at Westlake High was graduating, leaving the position up for grabs.

“His mom and I weighed the positives and negatives,” Marchell Henry said. “We wanted what was best for Malik.”

This is the personal side of what coaches and administrators describe as a growing transfer culture. Rosters get shuffled every time an athlete switches teams, and the Henry family’s decision sent a handful of players scattering in all directions.

--

Nestled against the foothills north of Los Angeles, Westlake High is the kind of place where the football stadium is crowded on Friday nights and the team regularly contends for league championships.

The coach, Jim Benkert, used to rely on players sticking around for four years.

“With this generation, when they don’t like the way things are going, they up and leave,” he said. “Sometimes they don’t even say goodbye.”

Malik’s decision to play for Westlake in the fall of 2013 made Benkert’s team better, but also presented him with a new set of problems as word of the transfer spread throughout the program.

People said Malik had an accurate arm and quick feet. They said he was coachable.

Wes Massett, a junior expected to compete for the starting job, quickly switched to Crespi High in Encino, saying: “I wanted a place where I could have a fresh start.”

Over the next year, four more quarterbacks left, transferring to schools throughout the region. The ripple led to more rosters getting rearranged.

“To be honest with you, it’s very difficult coaching in this era,” Benkert said. “It concerns me more every day.”

With quarterbacks leaving over the summer, the contenders for Westlake’s top spot heading into the 2013 season soon dwindled to Malik and a senior who had waited three years for his chance.

--

Switching schools was a gamble.

Despite his reputation, Malik left behind a premier team — Oaks Christian has sent numerous players to major college football — with no guarantee of starting at Westlake.

“A lot of people wondered if it was a good decision,” said Marchell Henry, a strapping man who played college basketball in his youth. “If it backfires, I look like an idiot.”

Arriving on campus, Malik stated his case to Benkert in businesslike fashion, informing the new coach he was ready to play.

His main competition was Tommy Gonzales, who had excelled on the sophomore team and, as a junior on the varsity, had passed for more than 400 yards in limited appearances.

Malik says Tommy showed him the ropes at first and they got along well. Then the sophomore pulled ahead on the depth chart.

“Tommy got real quiet,” Malik recalled. “Our relationship went south.”

Tommy and his father initially agreed to be interviewed for this article but put off scheduled meetings and eventually stopped returning calls.

“A transfer shows up and steps right over kids who thought they were going to play,” Benkert said. “It can be a problem.”

Massett faced a delicate situation with the returning quarterbacks at Crespi, saying: “You’re obviously not going to become best friends.”

By late August, Malik had won the job at Westlake and school administrators say they had confirmed Marchell Henry was renting an apartment in the area, meaning his son was immediately eligible for competition.

Benkert used the new starter cautiously at first, building his confidence. As the season progressed, the Warriors went on a winning streak.

They ended up playing Malik’s old school, Oaks Christian, for the league title. Malik shows no hint of emotion — no I-told-you-so smirk — as he recounts firing a dart to a receiver slanting across the goal line in that game.

Westlake eked out a 39-36 victory and the Henry family began looking forward to college scholarship offers — the ultimate payoff to their gamble.

“It’s competitive,” Marchell Henry said of the recruiting race. “Obviously, the sooner you can showcase your talents, the better.”

--

On a warm spring morning, months after the season’s end, Malik returned to a mostly empty Westlake stadium for a seven-on-seven passing game.

His feet tap danced across the turf as he rolled out, looking for somewhere to throw the ball. It took some patience but, finally, he spotted an open receiver and whistled a pass into the end zone.

Only a few people watched the scaled-down competition, which gave quarterbacks, receivers and defensive backs a chance to stay sharp during the off-season. Sitting in the stands afterward, Malik and his father talked about the events of the last year.

“It was the right thing to do,” Marchell Henry said. “Everything has turned out well.”

Scholarship offers have rolled in from USC, UCLA, Ohio State and other major programs. With two years of high school remaining, Malik said: “It’s a little overwhelming.”

Massett has been just as satisfied with his move to Crespi, where he has recovered from a mid-season injury and expects to start again this fall.

“Kids should be able to put themselves where they can be most successful,” he said. “If that means moving around, they should be allowed to do that.”

The argument makes a certain amount of sense to Benkert, who knows how badly young men such as Malik and Massett want to succeed. Still, the coach wonders whether something has been lost.

Patience, hard work, loyalty — Benkert believes the old way teaches something more than football.

“It’s the story of life,” he said. “You don’t always get what you want right away.”

david.wharton@latimes.com

Twitter: @LATimesWharton

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.