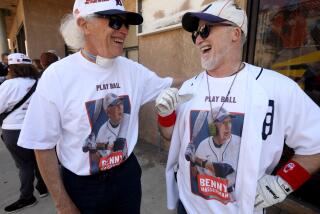

Tommy John pitches his surgery story to new generation with specialist son

Achilles had his heel, and in 1974 Tommy John had a similar career-crushing vulnerability — a lousy ligament, some really bad beef.

The rest, as they say, is sports history.

If John received royalties for every career he’s helped to save, for every multimillion-dollar season he’s fostered from afar — from John Smoltz’s to Carl Crawford’s — he’d be a very wealthy man. As it is, he’s awfully rich in other things, including a name synonymous with second chances.

In 100 years, they probably still will be talking about some young gun undergoing “Tommy John surgery.” You have to go back to Jarvik and his ersatz heart to find a moniker so associated with medical rebirth.

So, if Cooperstown is a celebration of generational legacy, then John should be there one day. As Patient Zero in a procedure that has revolutionized the game, and an expert voice on the issue of overworked young arms, he’s more relevant than ever.

The Tommy John saga: “It’s a Wonderful Knife.”

Here’s the opening scene: John had such a horrible stammer in high school that administrators back in Indiana refused to let him deliver the valedictory speech.

“Then last year, 53 years after graduation, they invited me back to give the speech,” John says.

“In high school, I may have been a better basketball player than I was a baseball player,” John said. “I got 50 scholarship offers to play college basketball. I got one to play baseball.”

Here’s the second act: His 38-year-old son, Tommy John III, is a chiropractor with a sports medicine resume. Together, they spoke at an elbow and shoulder symposium in Cooperstown last week.

“It was like we were right back in the game again,” the son says of appearing together. “Our mission is one and the same: to find the root cause of this American baseball epidemic” of bad elbows.

John and his son could go on all day. While the surgeon’s knife may have been wonderful to the pitcher’s career, he’s increasingly worried about how common the procedure has become. With better care and mechanics, the father-son team hopes to help kids avoid surgery.

Of course, Dodgers fans know the backstory: How their amazing sinkerball pitcher seemed done, until Dr. Frank Jobe in September 1974 stitched a tendon from John’s right arm onto his bedraggled left arm.

In four months, John was throwing again. Post surgery, he would have three 20-win seasons — one with Dodgers, two with the Yankees — and play until he was 46, compiling 288 career wins.

“So, the first time I threw [after the surgery], I got my wife in the backyard with a glove,” he said. “My thought was that if I threw to her, I wouldn’t overthrow.”

Diamonds are forever, as is the indestructible Tommy John.

Now 72, he plans to move from the East Coast to Palm Springs this fall, replace a gimpy knee that’s been messing with his golf game, then jump on the soap box about the dangers of throwing curveballs too soon.

“I tell parents, when your kid can shave, he can throw a curve ball,” he says of the dangers. “To me, a breaking ball is a strength pitch. Most kids at 8-12 are not strong enough to get on top of the ball.”

He also encourages parents to let kids play multiple sports. “It takes the stress off of everything,” he says. “It takes the stress off your mind.”

John has some insight into the pitch count controversy surrounding Matt Harvey.

“The chances of Harvey getting hurt are less and less every time he throws,” he said, citing Jobe’s belief that the longer you go, the more reliable the tendon is. “Just to say that Matt Harvey can only throw 175 innings is shortchanging the team, the fans, the players.”

Once in the Southland, John hopes to spend more time on that very issue with his son, also a former ballplayer who, following a freak infection in his shoulder, gave up his MLB dreams for a career in sports medicine.

“I don’t think it’s just by chance that Tommy John’s son is in the healing arts,” the chiropractor says.

Final scene: When the young specialist decided to relocate from Chicago to San Diego this year, he quickly found a medical office, an apartment, then took a break along the water, where he spotted a fishing boat with “Tommy John” painted on the hull.

Turns out that, like him, the vessel was named for the living legend, and was now moored in California.

“Some things are just meant to be,” the son says.

Cut.

Twitter: @erskinetimes

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.