A flood of memories for Holocaust survivors

Painful memories have the power to surface fresh and raw, even after many years.

A great-grandmother once again can become a terrified little girl. A grandfather surrounded by friends and family can feel all alone in a vicious world.

So it was at the Los Angeles Jewish Home in Reseda the other afternoon, when the drama club put on a play.

The audience was made up almost entirely of octogenarians and nonagenarians. The cast ranged in age from 85 to 92.

The performance understandably didn’t rely on action. The principals mostly remained seated, reading their lines — although there was one onstage costume change, deftly maneuvered by 88-year-old Jeanette Schlesinger.

But when it was all over, one audience member in the front row raised his hand and started to weep as he spoke.

“I just want to thank you for bringing this story. I don’t want anybody to forget what happened to us. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you,” said Ernest Braunstein, 89, as friends quickly moved to encircle him.

Braunstein is a Holocaust survivor, one of about 60 who live at the home. As a young man, he was sent to three concentration camps — Auschwitz, Sachsenhausen and Mauthausen.

The play — about the ill-fated voyage of an ocean liner 75 years ago — took him back to that most terrible of times.

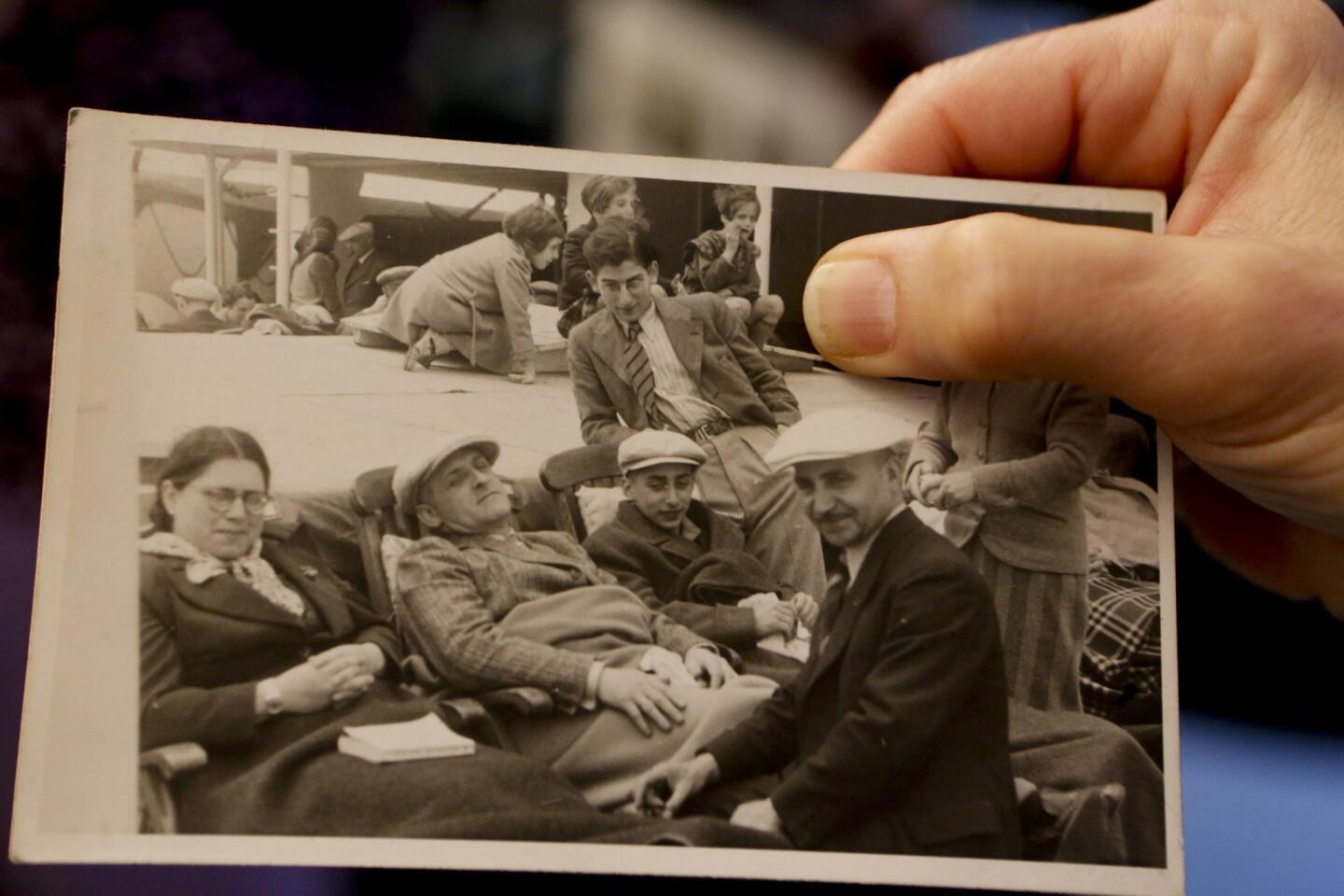

The SS St. Louis left Hamburg, Germany, on May 13, 1939, with more than 900 Jewish refugees on board. They were festive as they crossed the Atlantic, thinking they were leaving danger behind. But on May 27, when they reached Havana, only a couple dozen passengers were allowed to disembark.

Negotiations with Cuban officials went nowhere. Desperate passengers asked the United States to give them sanctuary. Though the ship, after leaving Cuba, passed close enough to Miami for its passengers to see the city lights, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declined to do anything to supersede the country’s strict immigration quotas. Canada also refused the passengers entry.

The ship was forced to make a grim return trip to Europe, where it docked in Antwerp, Belgium, and doled out its passengers to four countries willing to take them in: Great Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium and France. Three of those four later were invaded by the Nazis, and 254 of the passengers died in the Holocaust.

“The Trial of Franklin Delano Roosevelt,” which places much responsibility on the president and his administration, imagines FDR has been charged with crimes against humanity and asks the audience to serve as the jury. It was written by Robert Krakow, the executive director of the SS St. Louis Legacy Project, a nonprofit whose stated mission is to educate and promote discussion of human rights and immigration and refugee policy.

Ruth Ann Kalish, the project’s associate director, was at the Jewish Home for this performance and two others at its Fountainview independent-living facility. She said the audience/jury never fails to convict.

But to see such a judgment was not the primary motivation that Betsey Windmuller Roberts had for underwriting the performances.

Roberts, 61, of Sherman Oaks, volunteers at the nonprofit home. She is also the daughter of two SS St. Louis passengers, who were teenagers when they boarded the ship with their families.

Her mother, Ruth Heilbrum, then 13, was in first class. Her father, John Windmuller, then 15, was in tourist class. They didn’t encounter each other on board, but met later at a children’s home in France.

They stayed in touch and began a courtship when both came to America.

Roberts’ parents are now dead, but she saw the play five years ago when she and her mother attended a 70th anniversary gathering of passengers in Miami.

She said she wants more people to know the story of the SS St. Louis and what the United States’ refusal to accept the passengers wrought.

Before the performance at the home began, Lotte Seeman, 93, took her seat in the packed room. She recalled how Adolf Hitler had made fun of the passengers’ predicament. “I remember it. I remember every thing of it,” said the Holocaust survivor, who spent more than 21/2 years in an Amsterdam attic with her husband, hiding from the Nazis.

After the play, Hoffman remained in her seat for a long time.

“It’s too late for all that,” she said of the mock trial. “All our families passed away in the concentration camps. I lost my brother, my mother, my father, everyone. I was the only survivor.”

So too with Bella Roos, 92, delicate-looking in a red and white track suit. She was one of those who rushed to Braunstein. As he wept, she wrapped her arms around him.

Her own mother, she said, was sent to a concentration camp. She came from a large family in Munich and Vienna, and was the only one to make it.

“I had no place to eat or sleep for three years. I had to steal food. I was on freight trains,” she said in a tiny voice.

The play, she said, brought tamped-down feelings up. “I thought of all the family I lost.”

Follow City Beat @latimescitybeaton Twitter and at Los Angeles Times City Beaton Facebook.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.