Great Read: Buddies and budding actor, writer hustle to land their big breaks

The actor from Cleveland skimmed San Pedro in a banged-up Kia. He drove down a ragged street past a tattoo parlor and a sign for the Hotel Cabrillo. A few dicey-looking characters walked by with big dogs on chains. Robert McHalffey turned right and, betraying no trace of irony, parked at the Little Fish Theatre.

He walked down the hall and took a seat. Someone asked: “Who’s playing Puck?”

A whispery man near the window raised his hand. The rest of the troupe filed in. McHalffey opened his script to the part of Lysander, a suitor entangled in a comedy of errors in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Voices filled the dusk and McHalffey rehearsed for his first Shakespeare production, one that would pay $800 for 16 weeks’ work, better than the $125 he earned from a Budweiser commercial but not as good as the $1,000 he got for the ad for a hotel and casino in San Diego.

“I was naive. I thought as soon as I got done with acting school all I’d have to do is be good at this,” said McHalffey, who has black hair and a face twitchy with moods; he could be your frat brother or the guy who disappears with the stick-up money. “They say it takes 10 years to break into this business. I’m not giving up. I had an audition for ‘Grey’s Anatomy’ two months ago. Regardless if I get the part, I was in the room. They know who I am. It’s the little victories.”

The son of a retired mechanic, McHalffey, 29, wears the tattoo of a buxom angel and lives in the soul-bruising slipstream of acting, lining his resume with commercials, theater parts, short films and YouTube clips called “Ungodly” and “Pounce.” He has an agent and has been praised by talent coaches, but like thousands of others who have ventured in from the fields and rust of the heartland, his bills are mostly paid by waiting tables.

His friend of five years, who speaks in sentences that have the sting of meticulously aimed darts, is not always kind to McHalffey’s trade.

“Most actors are dilettantes,” said Marc Iannarino, 28, an Iraq vet, one-time publicist and former owner of a Porsche sold to finance his play about swingers, which starred his old roommate McHalffey. A perfectionist and budding iconoclast, Iannarino, who was born in Columbus, Ohio, often knocked on McHalffey’s door in the pitch of night to discuss the theater, politics, Charlie Chaplin and the thoughts crowding an insomniac’s mind.

“I’m neurotic,” said Iannarino, a slight man with delicate features and the blush of a beard that seems an afterthought. “I don’t sleep.”

He and McHalffey aren’t much alike, but they share the frequent disappointments and occasional satisfactions on the cruel edges of Hollywood.

The likelihood of career-defining breakthroughs is narrow; “almost-was” stories rattle in this town like mean charm bracelets. McHalffey, who aspires to be a character actor in the mold of John Hawkes, who starred in the HBO series “Deadwood,” and Iannarino, who’s shopping a screenplay for a “psychological thriller with horror elements,” are, depending upon your vantage point, clichés in a land brimming with insecurity, delusion and prescription drugs or talented novices chasing those elusive, tantalizing moments of artistic redemption.

::

“If you’re out there working at it you’ll get the opportunity,” said Iannarino, sitting with McHalffey at a Larchmont Village cafe. Boutique dogs and women carrying yoga mats slipped past. The lawnmowers of gardeners gleamed in pick-ups and one had the sense that the real world lived elsewhere. “When that opportunity arrives, it’s big stakes. There’s a lot on the table and a lot at risk. I’m absolutely terrified right now.”

Like the accountant he went to college to become, McHalffey calculated his chances in percentages. “I’m persistent,” he said. “I’ll keep watering the plant until there’s a plant.” He added he doesn’t have to vie with women or action hero-types for parts. His actor gene pool is specific: “I only have to compete with actors my type: 6-1 and who look like me. I have to be the best.”

The two men met in an acting boot camp class in 2009. McHalffey later entered the Elizabeth Mestnik Acting Studio in Hollywood, a two-year program that specializes in a technique developed by Sanford Meisner, an actor and coach who early last century emphasized that creating a role should spring from imagination rather than on memory and personal experience.

“I discovered how to live truthfully in imaginary circumstances,” said McHalffey, who works 34 hours a week in a restaurant and goes to as many as 16 auditions a month. “It’s like psychological warfare on yourself. You learn what you really care about, what your triggers are.”

Iannarino’s stepfather, an artist and college professor, enrolled him at the age of 8 in acting classes. His interest shifted to writing and directing after he joined the Navy, serving in an air-traffic control unit on the Abraham Lincoln in the Persian Gulf. He was discharged in 2009 — or as he puts it: “spit back out into the world.” He moved to Los Angeles with few prospects and eventually took a job in a publicist’s office.

“I used to go to a lot of parties in the hills,” he said. “I did a lot of drinking but not a lot of work. But I realized I wanted to write and create a vision.” Part of his inspiration came from his years on active duty in a military that “teaches you to make choices for self-preservation that you morally oppose.”

Iannarino wrote “Sacrifice,” a play about swingers, rape and the demons, egos and jealousies that burrow into relationships. “I sold my Porsche. My grandparents gave me a large chunk of money to make life a little easier. I threw this all into the play,” he said. “I didn’t want to compromise it.”

Undeterred by the narrow prospects of making it as a playwright, Iannarino rented out the small Sunset Gardner Stages in Hollywood. McHalffey played a husband who turns violent over his wife’s affair. The money ran out and the play closed after a month. A review on a blog called Screamplays praised the production’s “well mapped out scenes” and “on-the-dot dialogue” in a tale that unfolded “like an eerie opera.”

The experience was pivotal for McHalffey. “There was a scene where I should have broken down but I couldn’t,” the actor said. “I was disappointed in myself. I couldn’t dig to that place. I wanted emotional availability but it wouldn’t come and I was standing there live on the stage. I realized I had to work harder to find the deeper places. After that, I enrolled in Elizabeth’s school.”

McHalffey is a “tough type as far as being a young guy in his 20s. There’s just so many of them,” said Mestnik. “But the thing that makes Robert a little bit special is that he works extremely hard. There’s sometimes a naivete [among students] about what it takes to be a master actor. Robert still really wants to be an artist.... He’ll be a late bloomer. He’ll come into his own down the road.”

::

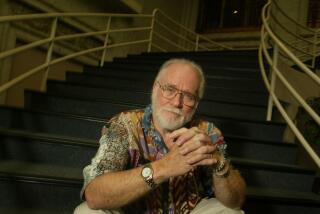

McHalffey and Iannarino met the other day before McHalffey’s rehearsal for “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Moving from sunlight to shade at a sidewalk cafe, Iannarino was at once cutting and precise, like a young Henry Miller, if Miller had cared at all about Hollywood.

Iannarino’s fascination with movies began as a child when he saw “Moby Dick” and he hoped his new screenplay, “The Light,” which he didn’t want to jinx by talking about too much, had the feel of “Chinatown” and “Silence of the Lambs.”

That was not, he said, meant to sound presumptuous. And it didn’t from a man quite at home with his opinions: “Fritz Lang was mind-blowing from the technical side … Welles was the guy who revolutionized everything.... Can you be devastated in front of people? Be naked and bare? That’s why I don’t act. I can’t do that. To find that life is a constant struggle. You’re constantly vulnerable to other people’s judgments just to do something you enjoy. To do it you have to be brave and a little crazy.”

That last bit was about his friend. McHalffey, who when not auditioning or waiting tables listens to blues at the Piano Bar in Hollywood, has the slow gait of a man wandering in a strange land. He has a distinctive nose and at certain angles he resembles the flint-edged starkness of Hawkes, nominated for an Academy Award for supporting actor for his turn as a meth addict in 2010’s “Winter’s Bone.”

McHalffey recalled a fellow waiter who left Maggiano’s restaurant in Los Angeles after writing and directing a film. Everyone thought she was on her way, but she returned months later, out of money.

Such stories have left him with an intensity that hides in a wry humor. He wrote an e-book, “The Ultimate Waiter,” offering advice on how to earn $100 extra a week in tips: clean your fingernails, wear non-slip shoes. “I wanted to create passive income,” he said of the book. “I earn about $30 a month from it. Gas money.”

::

The cast for the Shakespeare by the Sea series, which opened Thursday, gathered around pushed-together tables in a small room at the Little Fish Theatre; shards of scenery poked from behind curtains. The actors spoke of their first brushes with Shakespeare. For McHalffey, it was Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes in Baz Luhrmann’s “Romeo + Juliet.”

A few of them mentioned Kenneth Branagh. They were too young for Burton, Olivier and Gielgud. A late-arriving troupe member scurried in. Scripts rustled.

“I love first rehearsals because everything is still possible,” said director Patrick Vest. “Let’s dive in and get to work.”

Voices and inflections rose and fell; lines coiled, others found air. The poetry sharpened the syllables and the actors were bonded by old words that conjured potions, deceits and mistaken passion. McHalffey, his lines highlighted in pink, looked past a bag of chips to the star-crossed Hermia and uttered: “The course of true love never did run smooth…”

The director called for a break. The cast dispersed down the hall and into the parking lot.

“The key to Shakespeare is doing the detective work beforehand,” McHalffey said. “All my favorite actors are Shakespearean-trained. Patrick Stewart. Judi Dench. The language is moving all the time. The words work on you so you don’t have to worry about the emotion. It’s all in the language.”

He stood for a moment in the night. A slight wind lifted off the coast. The city had quieted. He walked back toward the glow of the theater, another young man with a battered car and a script.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.