Dorner and the LAPD legacy

I expected fireworks in South Los Angeles this week, when LAPD Chief Charlie Beck showed up at a community meeting to talk about Christopher Dorner, the ex-cop turned killer whose manifesto cast the department in an ugly light, resurrecting decades of buried wrongs.

The crowd at the Vermont Avenue community center was small, about 100 people. But the line to speak stretched from the stage to the back of the room. Some came for answers, some just to vent.

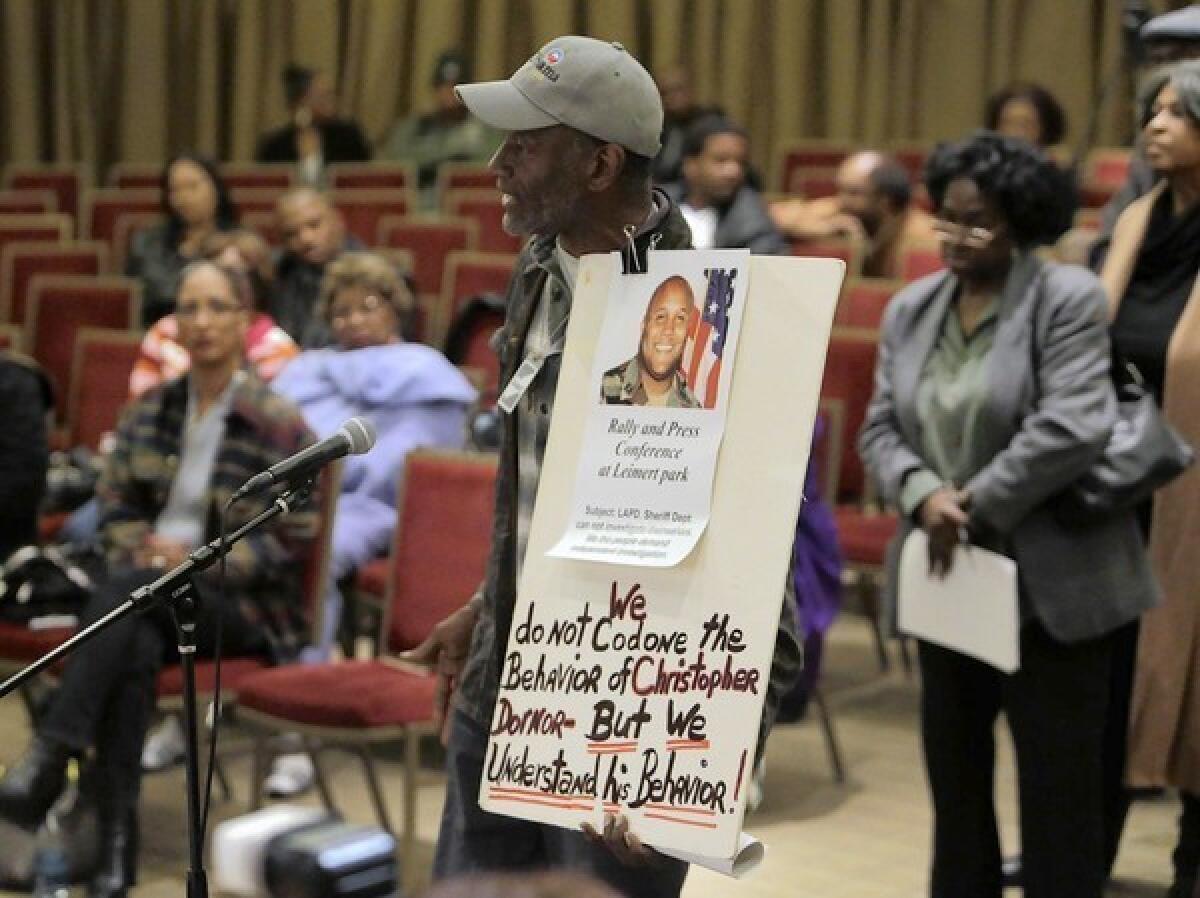

There were stories of ugly street stops and police harassment. Half a dozen people — black, white and Latino — said they’d had family members injured or killed by cops. An old man carried a poster of Dorner. A young man told Beck that the LAPD’s legacy runs so deep, “babies cry when they see your uniform.”

They had read Dorner’s manifesto, which blamed his firing from the LAPD on racists, liars and cowards. There were nods all around when one man declared, “I don’t defend what Dorner did, but like many in the community, I believe what he said.”

But no voices were raised, no insults hurled. Nearly everyone prefaced their comments to Beck with some version of “thank you for coming.”

It wasn’t exactly a love fest, but it was the sort of dialogue that would have unimaginable a decade ago, when the LAPD was regarded in the neighborhood as an occupying army.

“This is not us against them,” moderator Skipp Townsend told the crowd on Wednesday night. Townsend is a former gang banger who now “partners” with the department in crime prevention efforts.

“We’re going to be together, whether we like it or not,” he said. “This is like a marriage.”

::

If it’s a marriage, one spouse is feeling betrayed right now and the other is fumbling for answers.

A lot has been made of the ways the LAPD has changed since Rodney King and Rampart. The institution is more accountable, with video cameras in patrol cars and officers equipped with microphones. And the ethnic makeup now reflects the city’s demographics: 43% of officers are Latino, 35% white, 12% black, and 9% Asian American. Twenty percent are women.

Still, it’s unrealistic to believe that the LAPD has cleared its ranks of bullies and bigots.

Beck acknowledged that in South L.A. this week. “You will never have a perfect department,” he said. “We hire from the human race and we hire the best people we can, and sometimes they make mistakes.”

Some officers can be redeemed through discipline and training, but those with a “malignant heart” have to be let go, Beck said.

But how do you see into an officer’s heart and who determines its darkness? And how does an officer wind up fired for reporting misconduct?

That’s what residents wanted to know. And those questions are prompting soul-searching not just in the community, but inside the police department.

Dorner’s manifesto contends the deck was stacked against him. He was kicked off the force because a police panel ruled that he was lying when he reported that his training officer had kicked a mentally ill man they were in the process of arresting.

Official accounts lay out the evidence on both sides: The suspect’s father said the man’s face was puffy and that he described being kicked by a police officer. The training officer’s denial was backed by two witnesses who said they saw no kick during the arrest.

When Dorner challenged his firing, a trial court judge said the evidence left him “uncertain of whether the training officer kicked the suspect or not.” The case came down to the “relative credibility” of Dorner and the training officer. So Dorner lost his job.

Clearly, given his actions later, his was a “malignant heart.” Dorner was unfit to be a police officer.

But the account of his termination is troubling enough that it makes me wonder if the process was used to seek truth or simply to root out a troublemaker.

It looks like a Catch-22: Officers are subject to discipline for not reporting misconduct. But if you make the claim and it doesn’t stick, you can be fired because your bosses doubt you.

That’s a message with the potential to punish a whistle-blower. It seems to validate the “no snitching” mentality that once shaped the department’s culture.

Beck has promised to review the firing, and he’s assigned the department’s “special assistant for constitutional policing” to investigate Dorner’s claims of uneven discipline and racial bias.

But some in Wednesday’s crowd sense a whitewashing in store. “Why is the LAPD investigating the LAPD?” one woman demanded to know. And the room exploded in applause.

::

Old feelings die hard. Beck acknowledged as much. “I owe this community answers about how we discipline officers,” he told the crowd. “I recognize the mistakes of the past, and I don’t intend to repeat them.”

Beck understands that what happens next will help define his legacy as LAPD’s leader. And that requires that he navigate community suspicion, political realities and the sensibilities of his officers.

I can’t imagine how painful it must be for the LAPD’s rank and file to absorb this blow to the family. I understand the rumbling among officers who feel that giving any credence to Dorner’s claims risks turning a maniacal killer into some sort of martyr.

But I’ve also heard from officers who feel shamefully relieved that Dorner expressed publicly the frustrations some have been carrying privately for years.

Beck is meeting with groups of officers to talk about their concerns, complaints and difficulties.

“This has given us an opportunity to talk through difficult issues, involving race and gender and ethnicity,” said Assistant Chief Earl Paysinger, the highest-ranking black officer on the LAPD.

Beck needs to listen. But he must also answer to a public that needs more than reassurance right now.

The chief has promised to be transparent to expose just how fair his department is. But I hope he keeps an open mind. We need a willingness to go beyond transparency, to really ask if the department has changed, through and through.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.