Former inspector urges nuclear regulators to close California plant

A former federal inspector has urged regulators to shut down California’s last nuclear power plant until it can be determined whether the facility can stand up to an earthquake off the Central Coast.

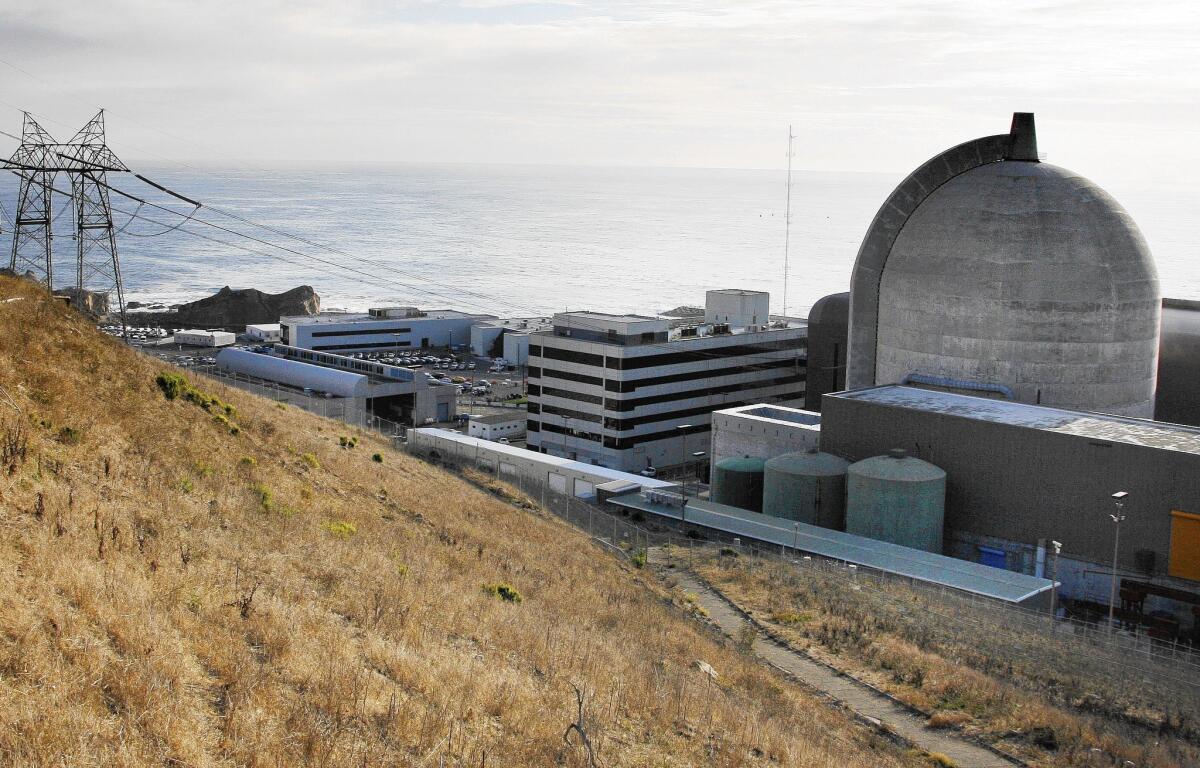

Michael Peck, the former senior resident inspector at the Diablo Canyon plant, made his case to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission in a confidential July 2013 document, a copy of which was released Monday by the environmental group Friends of the Earth.

Peck argued that it is unsafe to keep Diablo Canyon running without evaluating whether it can withstand quakes from nearby faults that are now believed to be capable of producing more shaking than was known when the plant was built and licensed.

Allowing it to continue operating “challenges the presumption of nuclear safety,” wrote Peck, who now works for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s training center in Chattanooga.

A new fault — known as the Shoreline fault — was discovered just offshore from the plant in 2008. Federal regulators concluded that the plant’s current design would be able to stand up to any earthquakes the fault might produce.

But Peck argued that the plant’s license needs to be amended in light of the new earthquake information. He also took issue with the methodology used to analyze earthquake risks at the plant in the past.

Damon Moglen, senior strategic advisor with the environmental group, said Peck was “the canary in the coal mine, warning us of a possible catastrophe at Diablo Canyon before it’s too late.”

Nuclear Regulatory Commission spokeswoman Lara Uselding said the agency stands by its conclusion that the plant would safely withstand an earthquake.

She said the agency “encourages and welcomes differing opinions” from its staff and is still reviewing Peck’s concerns, but has not issued a final response. Peck had made the same arguments in two previous documents, she said.

Blair Jones, a spokesman for plant operator Pacific Gas & Electric, said the plant “was built to withstand the largest potential earthquakes in our region.” The plant was retrofitted in the 1970s after the nearby Hosgri fault was discovered.

That retrofit fortified the plant to withstand the amount of ground shaking that could be produced by three other nearby faults, Jones said. The Hosgri fault is believed to be capable of producing a 7.5 magnitude earthquake, larger than the Shoreline and others in the vicinity.

Dave Lochbaum, director of the nuclear safety project at the Union of Concerned Scientists, said his group agrees that the methodology used to analyze earthquake risks at the plant was flawed, although he stopped short of calling for the plant’s shutdown.

He pointed out that the plant will be making seismic safety fixes in any case. Regulators ordered U.S. plants to make upgrades after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan.

“We hold out some hope that the Fukushima fixes will lead to the fixes needed at Diablo Canyon,” Lochbaum said.

U.S. Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.) — who has tangled with nuclear regulators in the past — said in a statement that she was “alarmed” at the agency’s failure to act on Peck’s recommendations.

“As we saw from the Napa earthquake, damaging earthquakes can occur at any time, and the NRC’s failure to act constitutes an abdication of its responsibility to protect public health and safety,” she said.

California’s other nuclear plant, San Onofre, on the coast near San Clemente, was shut down for good last year as a result of faulty equipment that led to a small release of radioactive steam and a heated regulatory battle over the plant’s license. Friends of the Earth and Boxer pushed to keep that plant shuttered.

The closure of San Onofre left energy officials scrambling to fill the hole in the power grid, and ratepayers wrangling with utilities over who should pay for the costs of the shutdown.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.