UCLA study offers hope on emergency room crowding

A new UCLA study has found that while people enrolled in low-cost, government-run health plans visit emergency rooms at high rates soon after becoming insured, the number falls dramatically within a year.

That’s good news, said study author and UCLA professor Dr. Gerald Kominski, because patients’ long-neglected health problems are being “addressed during the first year, and because of that there’s a drop-off.”

Some worry that the expansion of health coverage under the Affordable Care Act will not ease emergency room crowding as President Obama and others have predicted, but will instead encourage more people to go to the hospital.

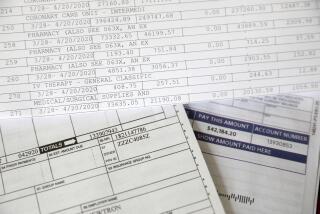

That increase was particularly expected among those who signed up for Medicaid, a long-standing free federal program for low-income people. Unlike private health plans, Medicaid patients typically are not required to make payments that might discourage them from making expensive trips to the emergency room. A study released earlier this year found that newly insured Medicaid patients in Oregon went to the emergency room 40% more than their uninsured counterparts in their first 18 months of coverage.

The new findings, from the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, examined a longer period than the Oregon study, Kominski said. Researchers tracked about 182,000 Californians who entered county-run programs for low-income residents between 2011 and 2013. The programs were free or low-cost, and structured similar to Medi-Cal, California’s version of Medicaid.

Researchers found that patients who hadn’t had medical care or any kind of health coverage before enrolling visited the emergency room at a rate of 600 visits per 1,000 enrollees in the first three months after becoming insured. By contrast, those who were already receiving care or had coverage — and therefore presumably had fewer unaddressed health concerns before enrolling — visited the emergency room at a rate in the low hundreds.

However, the study found the high usage dropped to 424 by the second quarter and 254 by the end of the first year, and then leveled off to a rate of 183 per 1,000 enrollees by the end of the second year. Kominski said these findings should be encouraging for states seeking to expand their Medicaid programs because they prove that fears are “completely unfounded” that the programs will bankrupt the state.

California expanded Medi-Cal in 2014 and enrolled about 1.5 million newly eligible people. A Los Angeles Times analysis found that the proportion of emergency room patients in Los Angeles County covered by Medi-Cal grew from 32% in the first quarter of 2013 to 38% this year, and that emergency room visits in the county overall increased by about 1% in those first three months of expanded Obamacare coverage.

It’s hard to say if expanding coverage alone will permanently reduce crowding in emergency rooms, said Dr. Renee Hsia, an associate professor of emergency medicine at UC San Francisco. Emergency room visits have been increasing nationally for the last two decades, she said, and not just because uninsured patients have nowhere else to turn.

Hsia published a different study Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Assn. that found that between 2005 and 2010, children’s emergency room visits in California increased across all insurance groups.

And, second only to the uninsured population, the group that showed the fastest rate of growth were the privately insured, not Medi-Cal patients. Hsia’s study found that the rate of privately insured youths visiting emergency rooms increased by 15% over that five-year period, while the rate of Medi-Cal youth increased only by 7.4%.

“It kind of refutes the idea that the ACA is going to solve all our problems,” Hsia said of the results. Health insurance is often thought to help cut down on emergency room visits because it gives people better access to outpatient care that’s cheaper and more efficient than visiting the emergency room.

But it’s not that simple, Hsia said; patients who want to see a primary care doctor can have problems finding one that takes their insurance, or getting an appointment with them, she said. And even when patients do manage to see a doctor, those physicians are increasingly sending patients to the emergency room for faster treatment.

Despite finding a significant drop in emergency room visits after two years, the UCLA study didn’t find a corresponding increase in outpatient visits that would be expected if patients were in fact going to doctors’ offices instead of emergency rooms.

“There’s multiple things going on” that affect emergency room visits beyond health insurance coverage, Hsia said. “It’s not going to be a one-stop solution.”

soumya.karlamangla@latimes.com

Follow @skarlamangla on Twitter for more health news

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.