Why kick the river’s rush?

This story is about coming of age — or not — on remote sand bars and in rural beer bars, so let’s begin it with Allison Atkin, because she’s tan, tipsy and toasting.

Atkin can’t remember whose idea it was to order the shots of Surfers on Acid, but it doesn’t really matter anyway, and not even the combined roar of two bartenders hollering “bottle or draft?” and the Coloma Club band jamming “Gimme Some Lovin’ ” can drown her out as 11 plastic cups of the brownish blend join hers and she blurts: “This the best job ever!”

Atkin and her pals are river guides, a trade whose nature is suggested in the band’s post-midnight farewell: “Hope you guys make it back to your tents OK.”

The guides, having moved on to Corona, chug their beers and single-file out, chanting hey, hey-ey, good-bye. Their two-car caravan curves past the farm houses lining Bassi Road and sputters into Camp Lotus, a former grape and pear field along the American River. A car alarm ruptures the silence. The sky looks like someone took the twinkling San Fernando Valley and flipped it into the heavens.

This is Gold Country, the place where the state’s rush for riches began playing out along the American’s south fork in 1848. This also is Guide Country. During spring and summer, an estimated 1,500 sun-bleached men and women, mainly young, will arrive to take the helm on inflatable rafts and lead corporate folk and families down California’s feral waterways — notably the American, Tuolumne and Merced.

Mother Lode highways zigzag along these rivers, with towns such as Angels Camp and Groveland crowning the surrounding cupcake hills. If you spot a string of extended-cab pickups, with plates from enough states to suggest some national convention, chances are you just zoomed by guide housing.

Guide life is spartan. Showers are rare or icy. Therm-a-Rests outnumber Beautyrests a thousand to one. One hundred bucks a day is considered good pay.

Still, there’s this: The put-in spot for the American River’s middle fork is called Oxbow, and it might as well be named Wish You Were Here. Under a cloudless sky, regiments of Ponderosa pines march down steep canyons to glassy water.

It’s easy to get beached on these Sierra riverbanks, all pine scent and gurgling rapids, with relationships as hard to hold onto as a fistful of water. Guide Country can be a confusing place to plot a course, to decide who and what’s important.

Guide life I

Tag along on the American River’s middle fork. Watch as the guides strap corset-tight life jackets onto passengers who already have signed liability waivers that caution: “I am going on a whitewater rafting trip — not a Disneyland ride.”Listen as the boats, filled mainly with women in their 20s and 30s, approach a rapid whose thunderstorm growl hints at what’s to come. Optimistically named Last Chance, it is only the warm-up act for Tunnel Chute, a Class V (on a scale of six) stretch of whitewater that roars down a channel that miners blasted through the granite in the 1890s.

The rafts drop. Passengers’ stomachs follow. The guide shouts “Get down!” and fingers clamp onto paddles until knuckles pale.

At the bottom, many passengers’ eyes have an odd glint of gratitude for the dude in the Hawaiian shirt and shades who steered them through: Mike “Roosta” Li, a 32-year-old lawyer whose clients include Safeway.

Li plunged into adulthood driven by longings for prestige and cash. He fast-tracked through UCLA but decelerated at Georgetown’s law school when cancer invaded his saliva gland. The bout scarred the right side of his neck. He had the life’s-too-short epiphany. In 2000, he gulped up guide school and, enraptured, drank in river living for two full seasons with the American River Touring Assn., or ARTA. Only when his bank account drained did Li return to San Francisco’s harsh office lighting and the strange feel of sleeping boxed in by walls.

After Atkin’s toast, he slept at Camp Lotus, curled on deflated rafts.

Li shrugs off the image of guide as Lothario, saying that the most attention he’s received was from some Girl Scouts in the nail polish stage, who begged to pretty his toenails.

“He’s in denial,” says guide Brad Faulkner, 26, from under a ball cap that shades sharp cheekbones.

When a passenger asks Faulkner if he has a girlfriend, his “no” inspires a lifting of eyebrows. A couple of hours later, the appreciation gets less subtle, as the guides portage the boats around an unrunnable Class VI rapid called Ruck-a-Chucky Falls.

Trudging along shore, Faulkner clings to a rope attached to an empty boat, eventually pushing it over the drop.

To make the whole show more exciting, the boat misbehaves, slithering onto the rocks. Faulkner scurries down the portage trail and up to a two-story boulder, where he discards his $1.50 button-down shirt and refastens his life jacket over bare skin.

“Ooooh, Brad’s getting naked,” a passenger whispers from the trail.

“Oh my God.”

“Did you see that?”

At the bottom of the rapid, Li leaps thud onto the raft and paddles it out of the whitewater into an eddy. To the guides, this is routine. On the sidelines it’s wow.

Faulkner reappears:

“You’re a rock star.”

“You’re a stud.”

Such comments, tonight, lead nowhere.

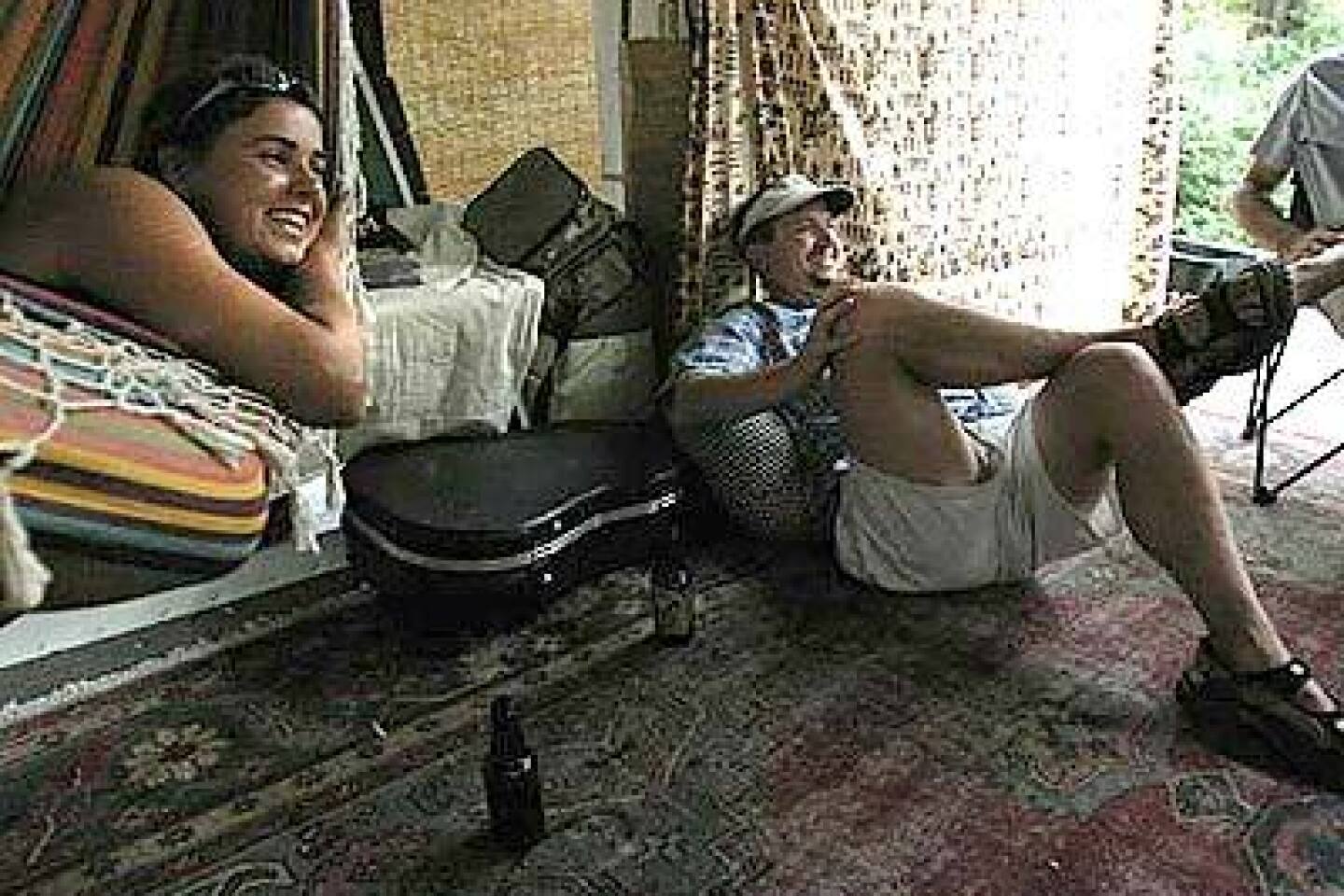

Sleepy to begin with, the town of Coloma is snoring when the ARTA van pulls in. Faulkner and Li scrape mud off their Chaco sandals onto the van’s already caked floor, then amble into the Camp Lotus guide hangout, a cabana-style frame, where they drop too.

This is guide life: The sweetest pad is a six-person tent. Washing machines and Yahoo inboxes are nearly nine miles away. From a beam, a gauzy blue bra dangles. Calvin Klein, 34C. Anyone know whose it is?

As the night progresses, other guides pop in: the new guy dubbed “Teen Beat” because he’s just old enough to vote. The former accountant who refused to sign up for company rafting trips (too expensive). Sprawled on a futon and brushing her toenails bubble-gum pink, Atkin, 25, says she has no use for any guy who would pay to raft.

Which leaves her stuck. Her mom warned her to never marry a river guide.

Guide life II

Squiggle south on the Mother Lode highways through a Golden State frozen in a pre-strip-mall era. Buildings advertise hay and grain. From the Groveland area, population 3,400, shuttle buses creak to the Tuolumne River. Just call it “the T.” Those who earn their living running it caffeinate at La Casa Loma, a mishmash of organic coffee and river community politics: Note the waterproof ammo boxes and “Save the Clavey” bumper stickers.Out front, a Subaru Outback Sport gathers layers of dirt. Jay McGuire, a 29-year-old guide with Outdoor Adventure River Specialists, borrows a pen and paper and dashes to it. Back in the van, he explains that it’s his girlfriend’s car. “I told her that I loved her and I hope she had fun and I won’t be back for three more days.”

“See!” says another guide. “That’s why you can’t have a relationship — you have to leave a note on the car.”

McGuire insists that his girlfriend, also a guide, gets the hippie-haven life. Still, this former Texan, who punctuates big water with “Yeeeee-haw,” is a natural storyteller, and many of his tales — Remember when those tequila-loaded women conga-lined back to camp — hint at the peculiar currents that can undercut commitment.

As the bus rumbles toward put-in, some of the passengers were no doubt sizing up the testosterone-only crew like personal ads.

Bruce Mitchell: Runs an adaptive-sports nonprofit in Mount Shasta. Single. Guiding since he had to sneak over the fence into the Coloma Club. Says this summer is his last — his refrain for three years.

Billy Paul: Raised in Granada Hills. Suffers off-season jobs at such places as Christmas tree farms. Returns to the rivers despite what he admits is an aching, homeless feel.

James Rodger: Carries a water-warped Mark Twain. Is pondering a wife and kids. In fact, there was a nurse in Edmonton. Until the calendar flipped to June.

The shuttle wobbles up, up, up a canyon road. Pines and oaks cloak the north-facing canyon. A balding slope looks south. Miwok Indians once harvested acorns here. Miners pick-axed gold. Suburbanites rodeo five miles to the confluence of the Clavey River. They relax. Water massages them amid rocks with tiramisu layers. Inhibitions fade.

Downriver, on a sandy embankment of riparian green, the guides begin nearly two hours of dinner prep, snickering as they list the reasons guides make great boyfriends: He’ll cook for you. He’ll share rent. And just when you’ve had it with him — poof — he’s sleeping next to a river.

Mitchell, hair dyed blond, admits to one post-trip rendezvous. Rodger, 28, with an aw-shucks demeanor, fesses up too. But, he says, that girl was his one-and-only for three years.

Quickly someone issues a caveat:

Q: How do you know a guide is lying?

A: His lips are moving.

Annie Khoury, a grandma tattooed with Hopi symbols, wiggles her toes in the water. In Flagstaff, Ariz., she knows her share of Grand Canyon guides. “They’re kids until they grow up. I think after they hit 40, maybe earlier, they start wanting to settle down more.”

Back in town that night, some guide buys the first round of tequila at a Gold Rush-era hotel bar; most keep pounding drinks until it’s time to vroom back to nearby Angels Camp. There, the guides wander off to sleep alone, Paul in the cab of his pickup with Tennessee plates, his head on a crocheted pillow next to a trash bag of dirty clothes.

Rodger cranks the volume from his Chevy 4x4. The groove is pure funk: Sly and the Family Stone meets “Shaft.” Chris Moore, a guide with the swagger and foldable leather hat of a cowboy, stands on a raft trailer and, in the light of a storage center, writhes. Some would call it dancing. It’s a mesmerizing scene, but lonely.

Guide life III

Alitia DANCIU and her boyfriend met on the river and followed each other across two continents doing the random things guides do: Whistler for a ski season, Colorado for shoulder surgery, Europe for kicks.It’s June. Home is a two-person tent. They sleep on self-inflating mattresses under a sleeping bag but — in a nod to luxury — atop sheets. Interior design is an empty Pabst Blue Ribbon can. Their view, though, is of bronzed meadow.

Four couples, all guides for Zephyr Whitewater, tent here. Their off days orbit around the porch of a double-wide. The boss’ instructions, Danciu says: “No playing bongos, no running around naked, no sex in the trailer.” One aspiring guide who lives here with his guide girlfriend calls the place “Guide World.”

All this leaves Danciu, 27, conflicted. With a runner’s build and rebel’s nose stud, she seems every bit the guide — not at all the type who’d pine over bridal magazines. Sprawled in a camp chair beneath a giant oak, she proclaims: “I can’t imagine not having any river in my life.” Yet, she’s at a point of yearning for something.

It’s the bowl of cherries that haunts her. A pal from high school, who lives in Nevada City, plucked them from her neighbor’s yard. They seem plump with prospects: a Victorian house and rose bush like her friend’s. Baby cries. Clanging pots and pans, a dog’s bark, food that wasn’t some passenger’s rejects.

The next day, at Zephyr’s ramshackle office-gathering point on the banks of the Merced, outside Yosemite National Park, Rob Fletcher arrives from Santa Barbara for a month of nothing but rafting. His wife, Claudia Rumold, tiny when hugged against his linebacker build, introduces herself: “I’m not a river guide. I’m just married to one.”

A grad student at UC Santa Barbara, Fletcher’s thesis is his life, scrutinized: the cultural anthropology of adventure travel, with whitewater rafting as a case study.

At put-in that day — a spiky metal bridge that fell out of some fairy tale — Fletcher, 31, hauls his gear in a gray life jacket, upon which he has puffy-painted the words: “Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it.”

Fletcher and another guide, Rosada Martin, have known each other since childhood, when Martin’s father, a raft manufacturer, would take their families on trips down the Kings River. The two fell for the life, and both began guiding. Martin, 26, will tell you the river is home.

As if cued, a blue heron swoops. A trail of merganser babies swims behind mama. The Merced River unfurls, banked with creviced mudstone, slate and pillow lava.

Martin’s boyfriend, also a guide, just got certified in electronics. He was gunning for a Real Job this summer. She dragged him to the river.

That afternoon, it’s she and Fletcher guiding through the misnamed Quarter-Mile Rapid — an intricate mile of waves that pinballs rafts into rock. Martin tells the passengers about her pal: “He always was running gnarly whitewater, running Class V all over the world because Class IV was too lame.”

The ride leaves the two physically whupped and well admired: “What the guides do is almost magical,” says one 18-year-old passenger.

That night, the stories, like most river tales, swell to “Odyssey” proportions. The gripping yarns can’t quite hold Fletcher’s full attention.

A week before they headed up to the Merced, his wife had turned to him and said, “I have to tell you something.” Long pause. “I’m pregnant.”

Fletcher said, “Are you serious?”

So let’s end with our father-to-be, his eyes groggy as he slips to sleep on an overturned raft outside Zephyr’s riverside building. At this point, the group’s plans are sketchy — maybe they’ll do another run or maybe they’ll just kick back and watch the river flow.

Times staff writer Ashley Powers can be reached at ashley.powers@latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.