A San Bernardino family terrorized by violence was desperate to leave before it was too late

She knew this summer it was time to leave San Bernardino.

Regina Bejarano was born in the city. So were her mom, her kids, her grandkids. She could probably drive through its neighborhoods with her eyes closed, she says.

But San Bernardino stopped being home on Aug. 31, the night two people walked up to the gate of her apartment with what she figures was a 9-millimeter handgun and a .22-caliber rifle, and unloaded on her family.

The bullets hit her 19-year-old son Kyle, her 25-year-old goddaughter and a 23-year-old friend. One went through a cluster of gold star stickers on the wall of her daughter’s room.

It was a miracle they all survived, Bejarano said.

But ever since, her five kids and two grandchildren have slept in the back rooms of her small apartment. Her sons stopped going to school out of fear of being attacked again.

After the shooting, she searched online for cabins in the mountains and rentals in Rialto and Fontana.

Two months later, on the day before Halloween, she was still trying to figure out how to make it work.

She came home that day about 9 p.m. and went into her bedroom to lie down.

Joseph, her 17-year-old — the one everyone called Joe Joe — left without her noticing.

***

San Bernardino has long struggled with violence, but 2016 has been one of its bloodiest years ever.

In this city of about 216,000 residents, 60 people have been killed — already more than in any year since 1995, when 67 people were slain. There have been more than 250 cases of attempted murder and assault with a deadly weapon.

All around here, every night, we hear fire engines. We hear gunshots.

— Regina Bejarano

The violence has occurred throughout the city, but certain neighborhoods are especially under siege. In some places, the sound of gunfire is routine. Seven people have been killed within a half-mile of one elementary school north of downtown.

The ferocity of the violence has come crashing down on a moment for hope in San Bernardino.

After four years, the city is finally on track to exit bankruptcy by the end of the year. Voters overwhelmingly approved a plan this month to restructure city government.

Last year, after a heavily armed terrorist couple killed 14 people and wounded 22 during a holiday party, city residents embraced the slogan “SB Strong,” a signal of their determination to keep pushing forward.

That spirit has moved countless residents here to dedicate themselves to improving the city. Church members comfort survivors. Coaches coax teens off the streets and onto basketball courts. Educators comb the streets for at-risk students.

But as the killings and shootings continue, it has become increasingly clear that there is no easy road out of San Bernardino’s long-term struggles.

In neighborhoods from the west side to the east, there are people like Bejarano who have had enough and are desperate to go.

***

Even before the shooting in August, Bejarano, 47, knew she wanted something better for her kids — Zondra, Kyle, Joseph, Jason and Amber, who range in age from 25 to 14 — than the rough San Bernardino neighborhoods she could afford to raise them in.

“All around here, every night, we hear fire engines. We hear gunshots,” she said.

She had dropped out of school in 10th grade and struggled as a single mom. Still, she had managed to get a GED and take some community college courses, and she encouraged her kids to take school seriously.

“You’re the only one that can get you out of this ghetto,” she would tell them.

Sometimes she worried about Joseph, who got in trouble for skipping school. But she remembered not wanting to go to school when she was his age.

She didn’t like that he smoked, but she blamed it on her own habit.

When he came home with a tattoo on his neck that said “Est. 1999,” breaking her rule against tattoos, she held her anger and laughed, telling him that he would never be able to use a fake ID because everyone would know he was underage.

She thought it was sweet, how he worked so hard to keep himself looking good — making sure his beard was cut just right and his eyebrows were in good shape.

He liked to look good for girls. An outgoing teen, he had friends in all corners of the city.

It was one of those friends the shooters were after in August, the family believes.

The friend had come to the apartment earlier in the day. When Joseph’s siblings figured out that someone might be after him, they asked him to leave.

“We got kids here,” Kyle remembered telling him.

The shooters arrived that evening.

Joseph was inside the apartment on Facebook Live and captured the sound of the gunshots on video.

“Get down,” he yelled at his 2-year-old nephew.

Bejarano was at work when she got the call. She sped home to find her apartment surrounded by crime scene tape and blood pooled on the sidewalk and near the door.

At the hospital she quickly learned that Kyle had been hit in the ankle and would face a long recovery to walk normally. But he would be OK.

Their friend, a cousin’s girlfriend, was hit in the leg and ankle. Her goddaughter had gotten the worst of it, hit in the head, stomach and chest.

The next morning, as Bejarano’s oldest daughter, Zondra, scrubbed blood from the driveway with a toothbrush, Bejarano began thinking of ways she could move her family out of San Bernardino.

“I knew I needed to leave before something happened to one of my kids,” she said.

I knew I needed to leave before something happened to one of my kids.

— Regina Bejarano

But even in nearby cities, it was difficult to find a place as affordable as her three-bedroom apartment north of downtown, where she paid $900 a month.

They had waited a long time for that apartment to open up. And when it did, Bejarano and her family were overjoyed.

As she looked for a new place, hospital visits and doctors’ appointments became part of the family’s routine.

Kyle had bad reactions to medication. Bejarano’s goddaughter was in a rehabilitation facility, learning to walk again.

On the day before Halloween, Bejarano came home exhausted from work. But Joseph and his cousins insisted on visiting her goddaughter, and she agreed to take them.

They packed into her room and talked about their lives growing up together, joking about how Joseph would try to escape punishment by taking the bus to church when he was young, Bejarano recalled.

When they got home, Bejarano’s daughter Amber, 14, called her to the bedroom and asked her to lie down with her.

About an hour later, her phone rang.

The caller screamed, “Joseph’s been shot.”

***

He hadn’t gone far, just a couple of blocks on the way to his cousin’s house — a walk he did probably every other day.

This time, the nurses at the hospital ushered Bejarano and her family into a special waiting room, and she knew her son had died.

“You know when they put you in the quiet room,” she said later.

The family believes Joseph’s killing had nothing to do with the shooting two months earlier.

Joseph’s alleged killer was someone he knew from middle and high school, they say. They were friends at first, then fought as ninth-graders.

They’ve also heard rumors that Joseph was killed as part of a gang initiation.

Joseph wasn’t a gang member, his family says. But he had so many friends, and some of them were.

San Bernardino police, who have struggled to solve many of this year’s homicides, made an arrest days later.

Miguel Angel Cordova, 18, is being held in county jail, charged with murder.

He faces a sentencing enhancement for allegedly committing the crime at the behest of a gang and has pleaded not guilty in San Bernardino Superior Court.

There have been no arrests in the August shooting.

In the mornings now, after she drops off her granddaughter, Bejarano drives to the spot where Joseph was killed.

It’s less than a minute from her home, but she doesn’t feel safe walking.

Joseph was found slumped near a tree in a neighborhood lined with small, aging homes whose front yards are filled with plastic toddler cars, slides and bicycles.

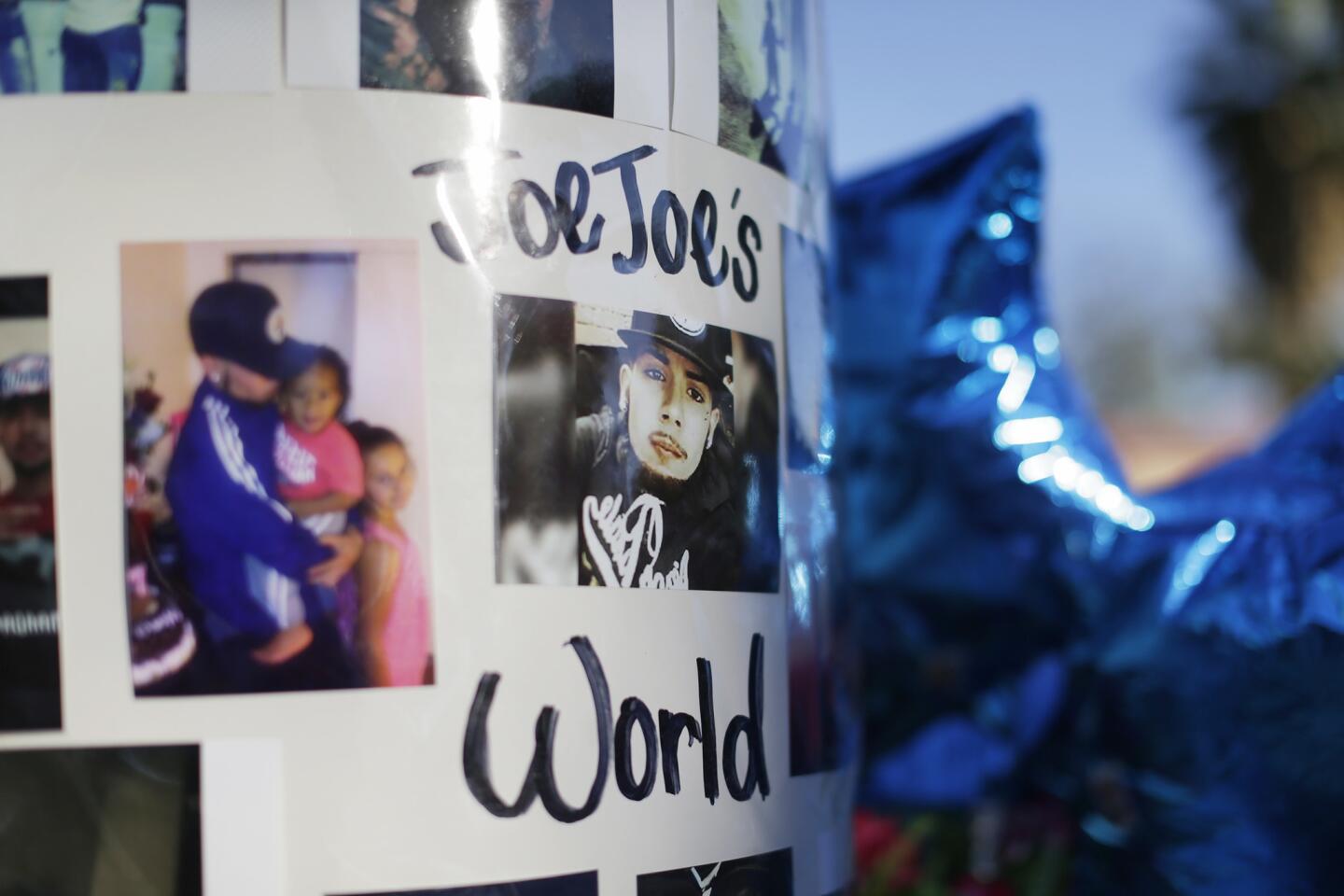

She sits on the curb, lights a menthol cigarette for her son and places it on the pavement, next to a cluster of candles and a collage of photos.

She wants more than ever to leave San Bernardino.

But all she can focus on now is burying her boy.

Twitter: @palomaesquivel

ALSO

Lawmakers reach a compromise to help California soldiers ordered to repay enlistment bonuses

Ex-NFL star Darren Sharper sentenced to 20 years in prison as rape victims in L.A. speak out

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.