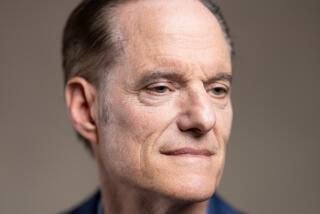

Ferd Eggan, 60; ally for those with HIV, AIDS

Ferd Eggan, whose innovative efforts as city AIDS coordinator included sponsoring Los Angeles’ first needle exchange program to reduce the transmission of AIDS through contaminated syringes, died Saturday of liver cancer at his home in Hollywood. He was 60.

FOR THE RECORD:

Eggan obituary: The obituary of former Los Angeles AIDS coordinator Ferd Eggan in Thursday’s California section said that he piloted the Safe House program and that it offered treatment to recovering substance abusers with HIV. Eggan wrote the proposal for the program, which does not offer treatment. —

Eggan was the city’s third AIDS coordinator, a position created in 1989 by then-Mayor Tom Bradley to spearhead the development of a comprehensive local approach to combating the spread of AIDS.

A longtime activist who tested positive for HIV in 1986, Eggan was appointed to the position in 1993 and served until 2001, when he became too ill to continue in the job.

Described by colleagues as brash, articulate and charismatic, Eggan championed public housing assistance for homeless people with HIV and AIDS and guided efforts to include women and minorities in AIDS policy-making roles. He also led the city to fund important research, including the first major study to demonstrate the link between crystal methamphetamine use and HIV risk in gay and bisexual men.

“He changed the face of AIDS in Los Angeles County,” said Cathy Reback, a research sociologist affiliated with UCLA who conducted the widely cited 1997 report on crystal meth and gay men called “The Social Construction of a Gay Drug.”

His most controversial initiative was the needle exchange program, which he viewed as crucial to the fight against HIV and AIDS. In 1994, Eggan worked behind the scenes to secure the cooperation of then-Mayor Richard Riordan, the City Council and the Los Angeles Police Department in a declaration of a state of emergency that allowed a local group to distribute clean needles without police interference.

Pushing for the declaration, which had more familiarly been applied in earthquakes and other natural disasters, was “appropriate and brilliant,” said David I. Schulman, who heads the AIDS/HIV discrimination unit of the city attorney’s office.

Eggan “led the city of Los Angeles to step right up to the line of supporting a well-run, principled local needle exchange program while not stepping over the line into supporting illegal acts,” Schulman said.

The program, which annually serves about 12,000 people, removed more than 1 million potentially lethal syringes off the streets last year, according to figures from the city’s AIDS coordinator’s office.

“There is no question in my mind that the program saved thousands and thousands of lives,” said Mary Lucey, an AIDS policy analyst who worked with Eggan.

According to Lucey, Eggan was one of the early voices warning that AIDS was not just a gay man’s disease. He helped Lucey and her partner, Nancy MacNeil, create Women Alive, a Los Angeles group focused on helping women with HIV and AIDS that is now a national organization.

Eggan was born in Alpena, Mich., in 1946. A graduate of the University of Chicago, he was a civil rights worker in the South in the 1960s before joining the Gay Liberation Front and helping to launch the Chicago chapter of ACT UP, the AIDS activist group.

He moved to Los Angeles in 1990 to work as executive director of Being Alive, which on its website describes itself as the city’s first organization to be run by and for people with HIV and AIDS. One of the programs he helped to establish was a dating service for those with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

As city AIDS coordinator, Eggan convinced Reback to undertake a study of crystal meth use among gay men because he suspected that the drug, which enhances sexual arousal, was contributing to the rise in HIV and AIDS cases. His hunch was correct: Reback found that 42% of gay men who were hard-core crystal meth users were HIV-positive.

With recent studies showing that the number of users is increasing, the drug continues to pose a serious public health risk.

Eggan “was the first person in a public position in Los Angeles to call attention to the crystal meth problem among gay men and its impact in amplifying AIDS transmission,” said Walt Senterfitt, an epidemiologist with the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health and chairman of Community HIV/AIDS Mobilization Project.

Eggan also piloted a program called Safe House, which provides housing assistance and treatment for recovering substance abusers with HIV. What set the program apart was that it did not automatically eject residents if they relapsed into drug abuse, a feature that riled critics who said that approach condoned drug use.

Eggan argued that the program was a compassionate solution to a complex problem. He told the Washington Post in 1994 that the program was especially important to him because he was a former drug user.

“People have forgiven me, and made space for me to make contributions in the world,” Eggan said. “The same should be offered to other people.”

Eggan, who is survived by two brothers, spent his last years traveling abroad and writing.

He sounded off on a wide range of issues on a personal blog, which he called “Communiques from a Cranky PWA [person with AIDS].”

A memorial service will be held at 3 p.m. July 29 at the Village at Ed Gould Plaza, Los Angeles Gay & Lesbian Center, 1125 N. McCadden Place, Los Angeles.

--

elaine.woo@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.