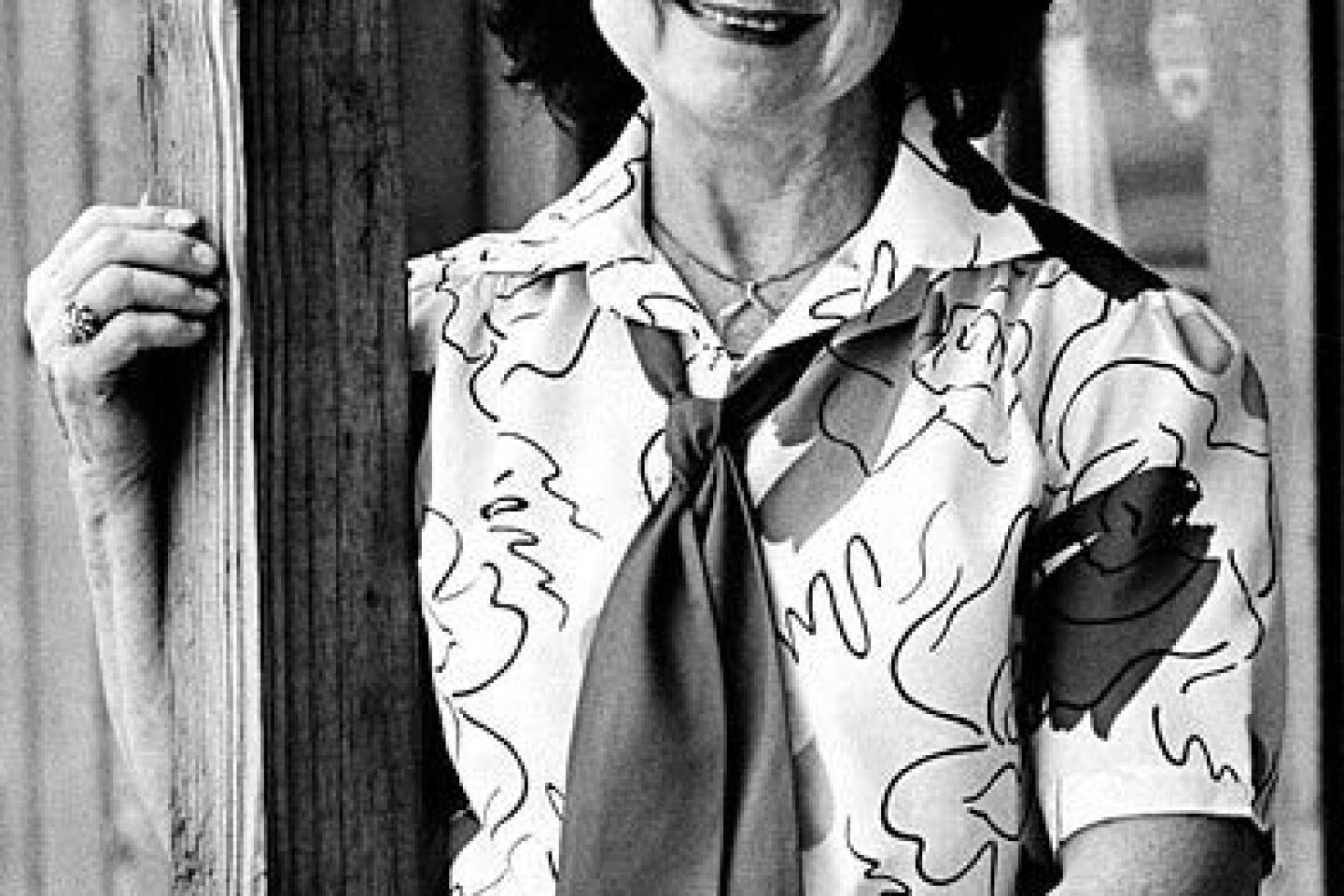

Kitty Wells dies at 92; country music trailblazer

Country singer Kitty Wells had been recording, touring and broadcasting without major success for more than a decade when she accepted an offer in 1952 to record one more song before she planned to turn her attention to staying at home and raising a family.

Mostly she was interested in the $125 union scale pay she’d get for the session, at which she recorded “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels,” a song that not only turned her career around but also helped upend stereotypical thinking about men who strayed and the women they strayed with.

“I had decided I wasn’t going to work any more,” Wells told a reporter in 2001 shortly after wrapping up a six-decade career through which she was often referred to as the “queen of country music.” “When it started making a hit, it wasn’t too long before I had to go back to work.”

Wells, who died Monday in Madison, Tenn., at 92 of complications from a stroke, promptly became the most successful and influential female singer of the 1950s and early ‘60s, one of a handful of women to have significant impact at a time when the music was overwhelmingly dominated by men.

“The history of country music can’t be written without calling attention to her great achievements,” John Rumble, senior historian at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, told The Times on Monday. “She really has left an indelible mark on American music history.”

Singer Marty Stuart on Monday called her “the undisputed queen of country music. There’s more to being a queen than just calling yourself a queen — it’s a title that goes with an entire lifetime of service and influence. You check the careers of anyone in [Nashville], and you won’t find anyone with a more spotless career than Kitty Wells.”

Wells laid a template for female singers in country music that started a shift in traditional male-female roles in rural America with “Honky Tonk Angels.” Her recording delivered a strikingly assertive response to Hank Thompson’s massive 1952 hit “The Wild Side of Life,” in which a man laid all blame on a woman he met in a honky tonk for breaking up his marriage and then leaving him to go “where the wine and liquor flows, where you wait to be anybody’s baby.”

Wells, singing a song written by J.D. Miller, shot back, “It wasn’t God who made honky tonk angels/As you said in the words of your song/Too many times married men think they’re still single/That has caused many a good girl to go wrong.”

That recording was No. 1 for six weeks in 1952 and began a string of hits that extended to 1979.

The stern resolution in her voice would be echoed in subsequent recordings by Patsy Cline, Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette, Dolly Parton, Emmylou Harris on through Shania Twain and the Dixie Chicks and still ripples today in assertive songs by Taylor Swift, Miranda Lambert and Carrie Underwood.

“Kitty Wells was my hero,” Lynn said Monday in a statement. “If I had never heard Kitty Wells sing, I don’t think I would have been a singer myself.”

Wells was able to defy conventional wisdom in country music during the first half of the century that said audiences wouldn’t buy records from female singers and wouldn’t pay for tickets to see them perform live. Consequently, women were typically relegated to supporting roles on Grand Ole Opry broadcasts, on multi-act tours and rarely landed recording contracts.

After “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels” sold more than 1 million copies, record executives began rethinking those attitudes and started signing singers such as Cline, Connie Smith, Lynn, Wynette, Parton and others.

Wells was elected to the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1976 and received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991 — the same year it was also presented to Bob Dylan, John Lennon and Marian Anderson. She was only the third country performer — and the first female — to get the recognition, following previous country lifetime achievement award recipients Hank Williams and Roy Acuff.

Wells continued to have an active role at the Grand Ole Opry long after country radio stopped playing her music. She placed 81 records on the Billboard Country Charts from 1952 through 1979 — 35 of those reaching the Top 10. She created the vast majority as a solo artist, but she also scored hit duets with her husband, singer Johnnie Wright; her daughter, Carol Sue, and several with singers Red Foley and Webb Pierce. Wright died last year at 97.

Muriel Ellen Deason was born Aug. 30, 1919, in Nashville, one of the very few major country stars born in the country music capital. Her father, Charles Cary Deason, and uncle were country musicians and her mother, Myrtle Bell Deason, was a gospel singer.

With two sisters and a cousin she began performing in the 1930s as the Deason Sisters, and after marrying Wright in 1937, she became part of Johnnie Wright and the Harmony Girls along with Wright’s sister, Louise. In 1939, Wright and his friend Jack Anglin formed a duo, Johnnie & Jack, for which Wells served as the “girl singer.” They toured throughout the South in the 1940s, and Wright began referring to his wife as Kitty Wells, a name taken from a 19th century song recorded in 1930 by the Pickard Family.

Recordings Wells made in 1949 and ’50 gained little traction. After the success of “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels,” she continued singing about the most disastrous effects of romantic liaisons and divorce — topics that still touched nerves and were considered taboo in many quarters — in subsequent hits such as “Paying for That Back Street Affair,” “Your Wild Life’s Gonna Get You Down,” “Mommy For a Day” and a No. 1 hit she recorded with Red Foley, “One by One,” in which the singers traded lines about how “one by one we broke each vow we made.”

“She was emotional, even tearful at times, but it was restrained,” Rumble said. “There was no emotional excess, no self-pity — it was just a lot of pain she was singing about in being ‘Mommy For a Day.’ ”

Wells deflected any aspersions that might have been cast on her own character because of what she sang by dressing conservatively, typically performing in high-necked gingham dresses with puffed sleeves.

“Her private life was family-oriented and without controversy, crisis or scandal,” country historian Mary A. Bufwack wrote about Wells in the new edition of the Encyclopedia of Country Music. “But in her songs, Wells could be the rejected woman or the barroom singer — worldly wise, a victim of her own passion or even morally weak.”

In the ‘60s she and Wright drafted their three children, Ruby, Carol Sue and Bobby, to tour with them as the Kitty Wells-Johnnie Wright Family Show — significantly with her name getting top billing. She hosted a syndicated TV show in 1968. The family’s touring ensemble kept busy playing as many as 300 nights a year until Wells and Wright announced their retirements in 2000.

In addition to her son, Bobby, and daughter, Sue Wright Sturdivant, Wells is survived by eight grandchildren, 12 great-grandchildren and five great-great-grandchildren. Her daughter Ruby died in 2009.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.