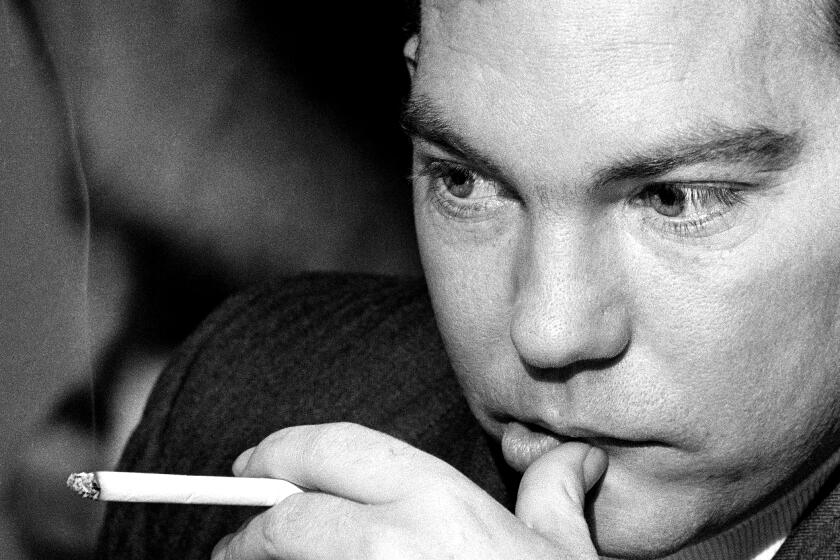

Lewis Baltz dies at 69; photographer of stark, postmodern isolation

Lewis Baltz, a photographer who offered a dyspeptic commentary on the American Dream with his stark images of Southern California tract houses and soul-sapping office parks, has died at his home in Paris. He was 69.

A chain smoker, Baltz suffered from emphysema and died of cancer, said Theresa Luisotti, a Santa Monica-based art dealer who represented him for years.

------------

For the Record

9:57 a.m.: An earlier version of this obituary omitted the day the photographer died. He died on Nov. 22.

------------

Pushing beyond an earlier generation’s taste for majestic landscapes, Baltz is credited with helping to secure greater critical regard for modern photography as an art form. Featured in museum collections throughout the world, his pictures are virtually free of humans but filled with the aftermath of human presence — construction debris, drainpipes, bare walls, blank doorways, half-finished roadways and bullet-pocked appliances rusting in the desert.

“It might sound ironic, but the attraction of his work is in the void — the emptiness that’s endemic to our culture,” Luisotti said. “And he would couch it in the most beautifully executed gelatin silver prints you could imagine.”

Baltz grew up in Newport Beach at a time that many Californians think of as safer, more laid-back, more optimistic — all in all, more Californian. As a boy, he picked up a nickname that other boys in Orange County would have fought for — “Duke,” after his father’s poker buddy, John Wayne.

But even before picking up his first camera at the age of 12, Baltz, who later described himself as “a repulsively serious kid,” was struck by his beach environment’s darker side.

“I remember when I was 7 or 8, walking around our seaside town, most of it looked like the desert with new houses,” he recalled in an interview earlier this year. “I thought the whole world couldn’t be this ugly, cold, and alienating.”

That impression only grew deeper as Baltz, who nearly flunked out of high school from sheer boredom, experimented with photography.

“I watched the ghastly transformation of this place — the first wave of bulimic capitalism sweeping across the land, next door to me,” he told The Times in 1992. “I sensed that there was something horribly amiss and awry about my own personal environment.”

Baltz’s feeling of post-industrial ennui wasn’t unique, but he was among the first to capture it with a camera.

In 1975, he was one of 10 photographers selected for a groundbreaking exhibit called “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape” at the George Eastman House in Rochester, N.Y. His contribution consisted of 18 prints from his 51-photo series “New Industrial Parks Near Irvine, Calif.” — views of mirrored windows, sliding garage doors and odd bits of shrubbery that effectively masked whatever was going on inside.

“You don’t know whether they’re manufacturing pantyhose or megadeath,” he liked to say, echoing the reaction of well-known museum curator Walter Hopps.

The show focused on mundane, depressing swaths of development on the fringes of the suburbs, forgoing calendar views of soaring redwoods or mountain summits bursting into the sunshine. It marked a controversial turning point for photography.

“I think it would not be too strong to say it was a vigorously hated show,” said Frank Gohlke, one of its original participants, at a 2009 restaging of the exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “Some people found it unutterably boring. Some people couldn’t believe we were serious, taking pictures of this stuff. And actually, that attitude is still very alive and well.”

Still, Baltz maintained his focus, turning his lens on construction sites in Park City, Utah, a desert dump outside Reno, trash-strewn Candlestick Point south of San Francisco and a garbage incinerator in the polar reaches of Norway. Later, he would examine high-tech installations from Silicon Valley to Singapore — and find them “impenetrable to vision” all over the world.

His work grabbed a generation of younger photographers.

“I’d say he was the first guy who was really out there,” said Connie Wirtz, a San Francisco art dealer and Baltz’s longtime friend. “He was the nexus for contemporary photography.”

Born Sept. 12, 1945, in Newport Beach, Baltz grew up around the local mortuary owned by his parents. When he was 12, he started hanging out at a camera shop in Laguna Beach, where the owner, William Current, taught him the basics of photography and effectively filled in for Baltz’s father Charles, who died when he was 11.

“Bill photographed the things — trees, rivers, the seacoast, prehistoric architecture in the Southwest — that he loved and admired, and used his photographs to better understand and bring himself closer to,” Baltz said in 2009. “My psychology was exactly the opposite: I used photography to distance myself from a world that I loathed and was powerless to improve.”

Baltz attended Monterey Peninsula College, made a lot of nature shots that he later destroyed, and received a bachelor’s degree from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1969. Two years later, he received a master of fine arts degree from Claremont Graduate School.

When he was in college, his mother, Lola, sold the funeral home.

“She told me that I was about to go into the world and would find it very difficult … and the idea of going back to Newport Beach to a safe business that’s making a lot of money might be tempting — and she wanted to remove that temptation.”

Baltz lived in Sausalito for several years. He returned to Southern California, which he described a few years ago as “my detested birthplace,” only occasionally and then not at all.

Baltz lived, taught and photographed in Europe since the mid-1980s, splitting his time between Paris and Venice.

His survivors include his wife, Slavica Perkovic, and daughter Monica Baltz.

Twitter: @schawkins

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.