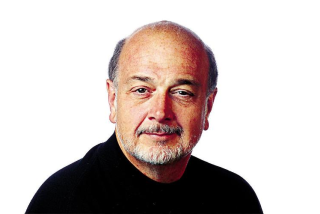

Sam Summerlin, correspondent who first reported the Korean War had ended, dies at 89

Former Associated Press foreign correspondent Sam Summerlin, who was the first to report the Korean War had ended and covered everything from Latin American revolutions to U.S. race riots during a long and distinguished career, has died. He was 89.

He died Monday at a care home in Carlsbad from complications of Parkinson’s disease, according to his daughter, Claire Slattery.

Summerlin had a second successful career as a New York Times executive and then a third as producer of scores of documentaries on historical figures and entertainers. But it was his days as an AP foreign correspondent that he treasured the most, he said in a 2004 oral history.

It was a job that gave him a window through which to view some of the world’s most historic events, as well as an opportunity to meet such disparate cultural icons as author Ernest Hemingway and Latin American revolutionary Che Guevara.

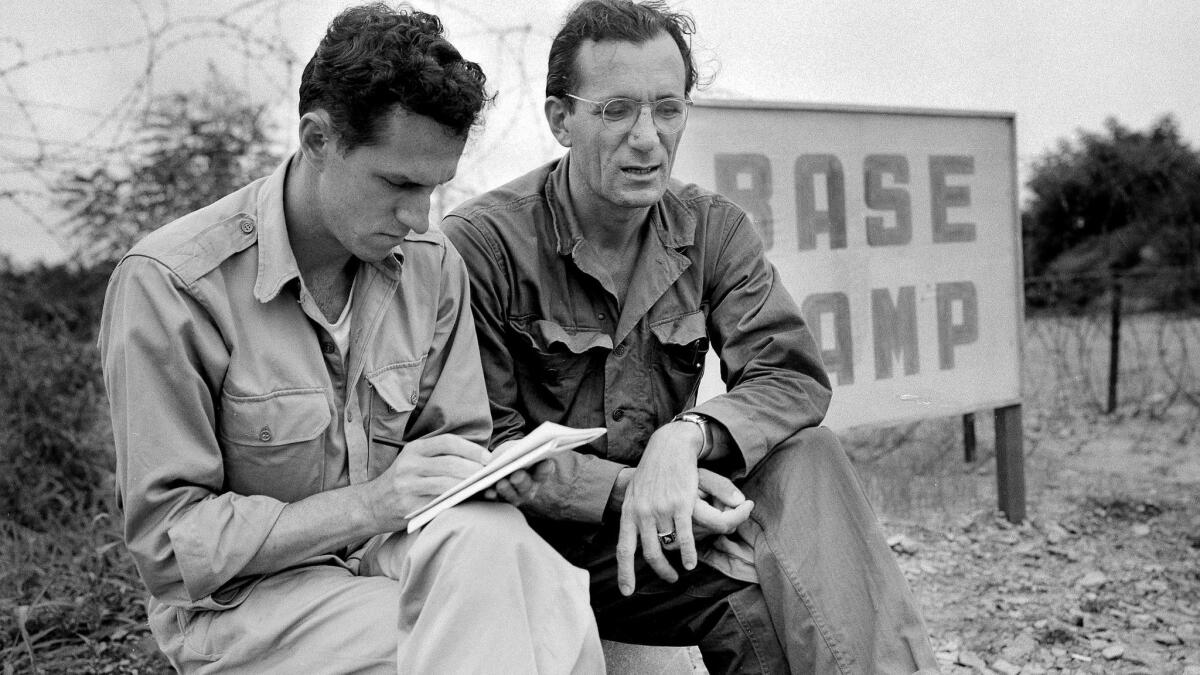

Summerlin was born on New Year’s Day, 1928, in Chapel Hill, N.C. He graduated from the University of North Carolina and joined the Associated Press in 1949. Two years later, he was sent to cover the Korean War, where at 23 he was one of the youngest war correspondents in Asia.

When the two Koreas signed an armistice ending the fighting on July 27, 1953, Summerlin was the first to report it. That was in large part, he said, because he weighed only 125 pounds and could outrun the other 200 or so reporters to the only telephone available at the signing ceremony in the North Korean capital of Pyongyang.

He was given just 15 seconds to dictate his report, so he recalled simply saying, “Flash: The Korean War is Over,” before handing the old-fashioned crank phone back to a military official.

After the war, the Associated Press sent Summerlin to Cuba. It was several years before the Communist revolution that would bring Fidel Castro to power, and Hemingway was living and writing in a converted lighthouse outside of Havana.

Summerlin went to drop in on the author one day, but when he saw an ominous sign written in English and Spanish ordering people without prior appointments to stay away, he decided to call first.

Hemingway, not known to like reporters, or anyone else who would barge in unannounced, so appreciated the courtesy that he invited him over. Several visits followed.

“We used to sit and talk about who should have won the Nobel Prize and all this kind of stuff, and it would be 20 million cats at the table when we had lunch — you know he loved cats,” he said.

When Hemingway won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1954, he gave Summerlin the first interview and agreed not to speak with anyone else until he had filed his story. Afterward, Hemingway asked Summerlin to organize his first post-Nobel Prize press conference.

Summerlin left Cuba to become AP bureau chief in Buenos Aires before Castro rose to power, but he returned years later with a small group of reporters, a visit he would jokingly say resulted in him making the biggest mistake of his career.

ABC’s Barbara Walters was in the group, and when Castro asked for an introduction, Summerlin, who spoke fluent Spanish, provided one. Castro immediately left the other reporters behind to take Walters on a personal tour.

“Don’t introduce a celebrity to the person you’re trying to interview,” Summerlin would say afterward.

He also confided that he never cared much for Castro or the Cuban leader’s famously long-winded, boring speeches, which he said would almost put reporters to sleep.

“Fidel had no sense of humor,” Summerlin said. “He was a brutal, tough guy.”

Guevara, on the other hand, did, and the two became friendly.

Summerlin recalled one meeting in particular, at an Alliance for Progress conference in Uruguay, when a photographer who had accompanied him approached Guevara. He proudly showed the Latin American revolutionary prints of 20 photos he’d taken of him over the years, pointing out there was no error in any caption.

“Che Guevara laughed and said the AP couldn’t be correct 20 times in a row if they tried,” Summerlin said.

While in Argentina, Summerlin covered several Latin American revolutions and was among the first to report the capture of Nazi fugitive and Holocaust architect Adolph Eichmann there in 1960.

In 1965, he moved to New York, where he worked as deputy news editor for AP. He left in 1975 to join the New York Times, where he was president and chairman of the newspaper’s news service and syndicate.

He later founded Hollywood Stars Inc., which produced video programs, and SAGA Agency Inc., which provided celebrity still photos and interviews. He produced TV shows for various cable channels, including biographies of Tom Hanks, Denzel Washington and Jamie Lee Curtis for the A&E Network.

He also authored or co-authored several books, including “Latin America: Land of Revolution” and “The China Cloud.” The latter was an examination of China’s development of nuclear weapons.

Summerlin’s wife, Cynthia, died in 2000. In addition to his daughter, Summerlin is survived by his son, Thomas A. Summerlin, and three grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.