He was the ex-husband from hell. And for nine years, she prepared for when he would finally attack

It was a happy marriage at first, though Dr. Connie Jones would later decide her husband was only pretending to be a good man.

By the end of their 22-year marriage, he was perennially unemployed, he stopped shaving and cutting his hair, and he seemed depressed.

“Looking at his eyes, there was nobody in there,” Jones told reporters Tuesday.

The final blow to their marriage came in 2009 when he threatened to kill her and kidnap their son, according to court records.

She filed for divorce and a protective order. But as is the case for many survivors of domestic abuse, her escape from her husband was only just beginning.

On May 31, Dwight Lamon Jones launched a killing rampage that left six people dead across the Phoenix area before he committed suicide as the police closed in.

The killings unsettled Arizona. But for Connie Jones, it was the end she had been fearing — and preparing for.

“I really have been on high alert for the last nine years. … I knew that one day we would be in a situation where he was trying to kill me,” she said at a televised news conference. “I felt that I had a personal terrorist.”

After she filed for divorce, Connie Jones hired an investigator, Rick Anglin, a retired Phoenix police detective, to protect her and her son.

They made themselves hard to find.

“Any personal habits they had, their favorite place to have a birthday dinner or Christmas Eve dinner, all this had to be changed,” Anglin told reporters at Tuesday’s news conference. “We basically had to de-program them from what they would normally do.”

The family cycled through three safe houses to avoid Dwight Jones, who had moved into an extended-stay hotel. Connie Jones, who worked at a hospital, rotated through rental cars and switched up her driving routes so she would be harder to pin down.

Even going to the grocery store required planning, in case of any unexpected encounters. When Jones went to the movies, she sat in the back of the theater to watch out for her ex-husband.

It was as if she had to become a different person.

“It has become my personality,” she said. “I don’t know that I can go out and not look and see who’s around me.”

Anglin also gave Jones “extensive” training with guns and defensive driving in case her ex-husband came for her. The pair spent a lot of time together, talking.

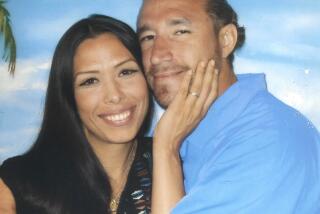

They became friends, and, eventually, more: They got married, and Anglin became her protector for life, and a new father for her son.

Connie Jones never actually saw her ex-husband again; she only communicated with him through lawyers.

She got custody of their son in the divorce, but Dwight got monitored visitation sessions. During the divorce proceedings, Dwight would sometimes try to track Connie, or show up at the child-visitation facility parking lot when she was there, Anglin said.

At one facility, he tried to kidnap their son, Connie said, and at another, he arrived with a sun visor in his car that said, “Love kills slowly.”

Connie was afraid that he would snap when the money she’d given him from the divorce — more than half a million dollars — ran out. He apparently never got the mental health treatment ordered by the court, and Connie was unable to obtain protective orders after four years.

She said she never stopped being afraid, recalling that he had told her “he could wait for a long time before he got his revenge, that he could wait years until my defenses were down.”

Investigators have not offered a reason for why Dwight Jones struck when he did.

His first victim was Steven Pitt, a well-known forensic psychiatrist who had testified during the divorce that without mental help, Jones “will become increasingly paranoid, likely psychotic, and pose an even greater risk for perpetrating violence.”

His next victims were Veleria Sharp and Laura Anderson, paralegals at the law firm of Connie’s divorce attorney, Elizabeth Feldman, who was out of the office at the time.

His fourth victim was Marshall Levine, a psychiatrist who shared office space with Karen Kolbe, the counselor Connie had hired for the couple’s son. Kolbe, too, was out of the office when Jones attacked.

Jones’ final victims were Mary Simmons and Byron Thomas, who did not have an apparent connection to the divorce case. Police said that Simmons sometimes played tennis with the killer.

As the number of victims grew, Anglin, holed up in an isolated cabin with Connie, recognized the links and phoned police.

The tip from the couple seems to have set authorities on Jones, and investigators surrounded him at the extended-stay hotel, where he shot himself.

The couple said they grieved for the dead and felt survivors’ remorse. The showdown Connie had prepared for never arrived.

“We were certain that she was the one who would have this final confrontation,” Anglin said.

But grief wasn’t the only emotion for Connie Jones. She felt “very happy” when she heard her ex-husband had killed himself, along with a “relief in my chest that this, for me at least, would be the last that I had to deal with him.”

Matt Pearce is a national reporter for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @mattdpearce.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.