Trump claimed credit for rising stock prices. Now he owns their fall — and a possible recession

Until the recent downturn, the soaring U.S. stock market had been one of President Trump’s favorite topics.

He’s tweeted more than 60 times since his election about new highs and frequently touted the gains in public comments.

“The stock market is smashing one record after another, and has added more than $7 trillion in new wealth since my election,” he boasted last month to corporate and political leaders in Davos, Switzerland.

Past presidents have resisted taking credit for rising stock prices because, as one aide to former President Obama tweeted recently, “if you claim the rise, you own the fall.”

The fall came this month, with the first 1,000-point nosedive ever for the Dow Jones industrial average. The Dow and broader Standard & Poor’s 500 dropped more than 10% — what’s considered a market correction — before recovering much of those losses in recent days.

Some economists said Trump owns this drop — along with the unwelcome return of market volatility and a possible looming recession — not because of what he has said, but from what he has done.

The Republican tax cuts that Trump championed and took effect Jan. 1 injected a large fiscal stimulus into the economy. And they appear to be having the intended effect. At their policymaking meeting in late January, Federal Reserve officials cited the tax cuts as one reason they were upgrading their growth expectations for 2018.

But critics say the cuts actually come at the worst-possible time — when a near-record-long expansion has the nation at full employment.

Then this month Trump signed a two-year budget bill that adds even more stimulus by boosting spending roughly $400 billion more than planned.

The moves could get the economy revving too fast while swelling the already large federal budget deficit. That would lead to rising interest rates and higher inflation — twin developments that would slow economic growth by making it more difficult for consumers and businesses to borrow money while at the same time reducing that money’s buying power.

It’s all a recipe for recession and the reason investors have gotten anxious, said Mark Zandi, chief economist at research and analysis firm Moody’s Analytics.

“It’s as if someone picked up a macroeconomic textbook and decided to do just the opposite of what it told you to do,” said Zandi, a former advisor to Sen. John McCain's 2008 presidential campaign.

“The economy is at full employment, and if you juice things up by cutting taxes and increasing government spending — all deficit-financed — the economy will get away from you,” he said. “It’s going to overheat.”

Billionaire hedge fund manager Ray Dalio estimated during an appearance at Harvard University last week that the odds were “about 70%” that the U.S. would fall into a recession before the 2020 presidential election.

A downturn already is overdue. Since World War II, the U.S. has averaged a recession roughly every five years. The current nine-year economic expansion is the second-longest in the nation’s history, and by mid-summer would be the longest.

Albert Edwards, an investment strategist at French financial services firm Societe Generale, declared this month that the tax cuts and additional federal spending amounted to “probably the most foolhardy escapade in modern economic policy.”

“Whatever the arguments are in favor of tax reform in the U.S. (and there are many), this is probably the singularly most irresponsible macro-stimulus seen in U.S. history,” he wrote in a research note to clients. “To say it is ill-timed and ill-judged would be a massive understatement.”

The tax cuts, focused on corporations and the wealthy, will swell the already large federal budget deficit by nearly $1.5 trillion over the next decade, according to Congress’ nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation. Even taking into account additional economic growth spurred by the tax cuts — a development that some experts doubt — the deficit still will increase by about $1 trillion during that period, the committee estimated.

Trump administration officials acknowledge the deficit will jump in the short-term. But they said that’s worth it to boost economic growth from the sluggish 2% level that has marked the recovery from the Great Recession and to further strengthen the U.S. military, where much of the additional funding will go.

“We inherited an economy that really had some serious problems … and we fixed that. And there was near-term cost to the deficit,” Kevin Hassett, chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisors, told reporters last week. “But I think, in the long run, we're going to be glad that we did fix those things. And we'll also be better able to address deficit problems because of all the extra resources we have because of a healthy economy.”

Hassett released a lengthy report Wednesday that estimated total economic output, also known as gross domestic product, would grow 3.1% this year and be at or above 3% through 2024. That is higher than the estimates from the Fed and some private forecasters.

Administration officials have downplayed the market gyrations, saying the economy’s fundamentals remain strong. And Trump’s supporters note that the major U.S. stock indexes still are up significantly since his election — the Dow about 38% and the S&P 500 about 28%.

For his part, Trump hasn’t had much to say about the stock market since the turmoil began this month.

On Feb. 7, he tweeted his lament that when good economic news comes out, “the Stock Market goes down.”

And on Friday, in a speech to the Conservative Political Action Conference, Trump acknowledged the markets “did a little bit of a correction.”

There is no doubt that the federal budget deficit is going up, and the increased borrowing by the U.S. Treasury is a key reason interest rates are rising as well.

The Treasury Department said this month that it expected to borrow $955 billion in the 2018 fiscal year, which began Oct. 1. The figure is a sharp increase from $519 billion last year and would be the most federal borrowing since 2012, when the economy was still struggling to recover from the Great Recession.

The borrowing ramps up to $1.08 trillion in fiscal 2019 and to $1.13 trillion the following year, the Treasury predicted. Those estimates came before the two-year budget deal, which will add to the federal government’s need to borrow money.

“Because of the tax plan and other spending that the government is doing, there needs to be more Treasuries in the market,” said Charlie Ripley, senior investment strategist for Allianz Investment Management, an advisory firm.

An increased supply of Treasury bonds — a near-record amount were auctioned last week — means buyers typically aren’t willing to pay as much for the new offerings, which pushes the yield up. The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury bond has increased significantly this month. It reached 2.95% on Wednesday, the highest since early 2014, before declining to 2.87% by the end of the week.

The increased yields affect not only newly issued bonds but also existing bonds that trade on the secondary market before they mature, because those existing bonds need to be competitively priced compared with new bonds.

The other pressure on interest rates comes from the Federal Reserve, which moves its benchmark short-term rate up or down in response to economic conditions.

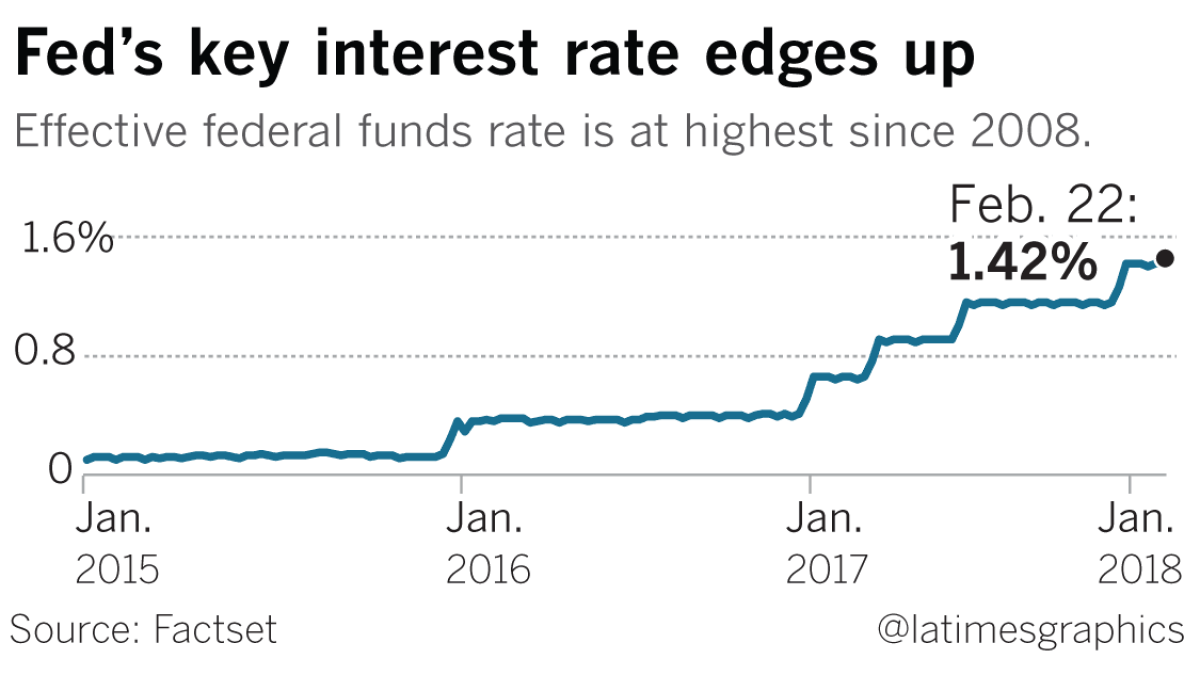

After keeping the federal funds rate at the unprecedented level of near zero from late 2008 until late 2015 to try to stimulate growth, Fed officials have been gradually moving the rate up to keep the economy from overheating and prices from rising too quickly.

The rate now is between 1.25% and 1.5%, and Fed policymakers have indicated it will top 2% by the end of the year. The federal funds rate is the interest rate at which banks loan reserves to each other overnight to meet Fed requirements. Banks use the rate to determine interest rates for credit cards, car loans, small business loans and home equity lines of credit.

Fears of higher inflation, which in turn could lead the Fed to accelerate its rate hikes, caused the recent stock market volatility. The big trigger was a Labor Department report Feb. 2 that said average hourly earnings in January jumped 2.9% over the previous 12 months, the largest year-over-year gain since 2009.

“The surprise surge in wage inflation … may have been the match that lighted the equity market turmoil,” Edwards of Societe Generale wrote in his research report, “but it was the irresponsible fiscal stimulus that provided the kindling.”

Those higher rates are not welcome on Wall Street.

They make stocks a less attractive option because it’s more expensive for companies to take out loans to expand and it costs more for customers to borrow to buy the products. Rising interest rates also generally signal an economic expansion is nearing its end, which can cause investors to flee stocks for relatively safer bonds whose yields are rising.

Fed policymakers also are to blame for the recent market volatility because they let stock prices rise to inflated levels without being more aggressive about interest rate hikes last year, said Desmond Lachman, a resident fellow at the conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute think tank.

That, combined with the additional fiscal stimulus coming from tax cuts and federal spending, led him to lament at a forum this month that “for the sake of one miserable percentage point of GDP we’re prepared to risk the whole economy.”

The rising deficits threaten to create a vicious cycle: higher interest rates that increase government borrowing costs that cause the deficit to swell further, Zandi said.

Because of “the poor policy decision” to inject deficit-financed stimulus now while the economy already is expanding at a healthy pace, federal officials will have less financial flexibility to add such stimulus when needed in a downturn, he said.

Zandi predicted the U.S. will be at a “very high” risk of recession in 2020. Such a downturn could be avoided if economic policy is executed just right, but he said that’s unlikely.

“It’s like putting someone on the Olympic ice skating rink who’s been ice skating for a year and saying, ‘Go do a triple axle,’” Zandi said. “Could they do it? Yeah. But I wouldn’t count on it.”

Twitter: @JimPuzzanghera

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.