A case so tragic, Covina police will never forget

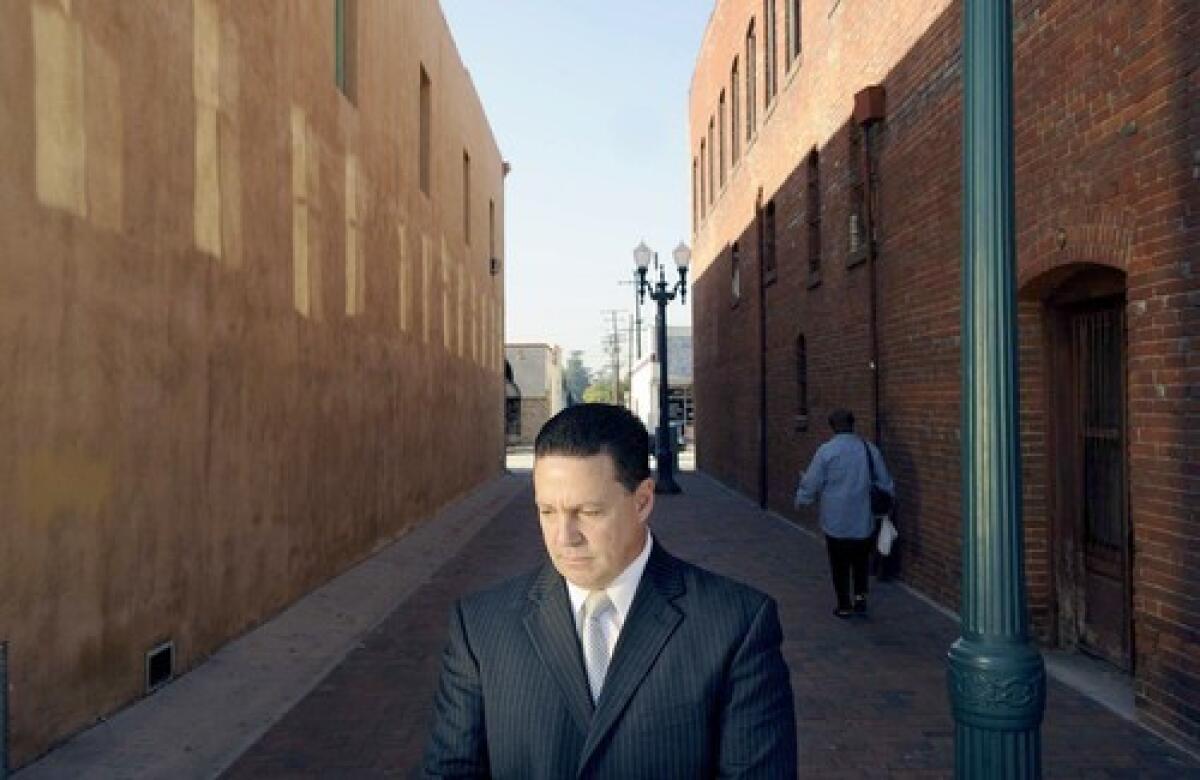

Covina Police Chief Kim Raney was relaxing at home with his family around midnight on Christmas Eve. Lt. Tim Doonan was making late-night preparations for the holiday morning. And Det. Dan Regan was in bed, just starting to doze off.

Then their phones started ringing.

“Units are responding to a shooting in progress,” the caller said.

No one knew it at the time, but the usually quiet San Gabriel Valley community was about to be catapulted into the media spotlight as police came upon a crime scene that would horrify the nation.

Apparently enraged over his divorce, Bruce Jeffrey Pardo, dressed in a Santa Claus suit, killed his ex-wife, Sylvia, her parents and six relatives during a holiday gathering at the Covina home of his former in-laws, police said. Pardo shot his victims and then set the house on fire, police said.

“For the officers on patrol that responded to this call, if they worked 30 years in this business, they will probably never respond to a scene or a call like this,” Raney said. “For detectives, they will probably never investigate a crime of this level of violence or horror in their careers.”

Pardo later killed himself near his brother’s home in Sylmar. And the police investigation grew to five crime scenes, including a booby-trapped rental car that bomb experts successfully defused.

For the city of 50,000, the magnitude of the crime was overwhelming. For its 60-officer police department that typically handles one or two homicides a year, it represented a daunting challenge.

“You couldn’t have a worse call happen on the worst day of the year,” Raney said. But they opted not to farm out the large-scale homicide investigation to the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, as many smaller departments do. The Covina Police Department had handled its own murder investigations for the last 12 years. The case would strain department resources and test its skill.

“If this is the biggest crime to hit this city, then we need to be the face of that, and we need to be the ones to lead,” Raney said. All of the department’s 12 detectives were called in. Det. Mike Robison loaded his family up and drove back from Arizona, arriving late on Christmas day; Det. Stacy Franco put his family on a plane to Texas for their planned trip and came in to work; Sgt. Trevor Gaumer left visiting relatives at home.

The department was swamped with calls. Lt. Pat Buchanan, who handles media inquiries, received 400 to 500 calls and did 46 television interviews during the first few days. Department officials also held two news conferences.

“We were the only news story in the United States,” Raney said, “and as the story continued to evolve, and we had the Santa Claus factor, it just drove the news cycle.”

Covina officers worked ‘round the clock; some slept in their cars or at the office, others grabbed catnaps at home before reporting back in for duty. The department was aided by nearly a dozen other agencies, including the L.A. County sheriff’s bomb squad and crime lab and the FBI.

A few days into the new year, Doonan sat back in his spare office, looking slightly worn. Next to him on the desk were three 16-oz. cans of Monster Energy drinks, and in front of him a long to-do list.

Even with the gunman dead, there were a lot of unanswered questions. How long had he been planning this? What was his motive? Did he have help? The investigation was far from complete.

“We owe it to the people of this state, and more than that, to this family, to make sure we go all the way through this investigation,” Doonan said. “This is the type of case where questions are going to be asked about it years from now, and we want to make sure we have those questions answered.”

The Covina Police Department has a close relationship with residents. That’s partly because of the department’s small size, but also because many of its cops, including Doonan, are home-grown and regularly attend Neighborhood Watch meetings and other outreach events.

Officers often spend their entire careers here, arriving as bright-eyed interns in their 20s, some right out of college. They work together closely and see one another often outside of work.

The Pardo case has been an emotional one for the tight-knit department. Many of the officers have young children who believe in Santa Claus. Two psychologists visited the department multiple times days after the violence, debriefing officers and 911 dispatchers and helping them cope with any associated trauma.

Law enforcement officers are usually on call during holidays, and when a tragedy occurs on such a special day, the memories can be hard to shake subconsciously even decades later, according to Nancy Bohl, director of The Counseling Team International, which consults with about 70 law enforcement agencies including the Covina police.

“I don’t think civilians understand how protective police officers really are over their communities,” Bohl said. “They don’t want anything bad to happen to them. They are the good guys. And when something like this happens in their city, or as they say, on their watch, they feel really badly. They feel guilty.”

The counselors urged officers to talk to one another and to their families, to avoid the tendency to “stuff it” or bury their emotions, Bohl said.

“That’s the kind of case that stays with you forever,” said Ray Peavy, a retired captain of the L.A. County Sheriff’s Homicide Bureau. He served that department for more than 38 years. “A smaller department like that, heck, a larger department, if I had to handle that case in all the years I worked homicide -- and I’ve done it 16 years -- I don’t know if I’d say I’d ever have a more bloody and sad case.”

Peavy said the Covina department appeared to be doing an “exceptional” job on a very unusual case. And although the case has galvanized the department, it has also left its mark on Covina’s officers.

“We will come out of this a different department,” Raney said. “Our sense of normalcy will be different now. We’ve been through a case that’s, it’s been tragic, and it’s had an emotional impact on everybody.”

Days after Pardo’s rampage, the department held a neighborhood meeting for those closely affected by the deaths, and then a citywide meeting that drew hundreds of residents searching for answers.

“We go the extra mile to let the public know,” said Doonan, suddenly leaning forward in his chair and speaking intently. “ ‘Joe Friday just the facts ma’am,’ that’s not us. We’re not just concerned about the facts. We’re concerned about the impact on the community.”

After the town hall meeting in the auditorium of Royal Oak Middle School, dozens of residents lingered to chat with one another and police officers.

Then a few raised their hands and put them together. A slow clap began and grew louder.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.