Redondo Beach hopes to recapture pier’s glory days

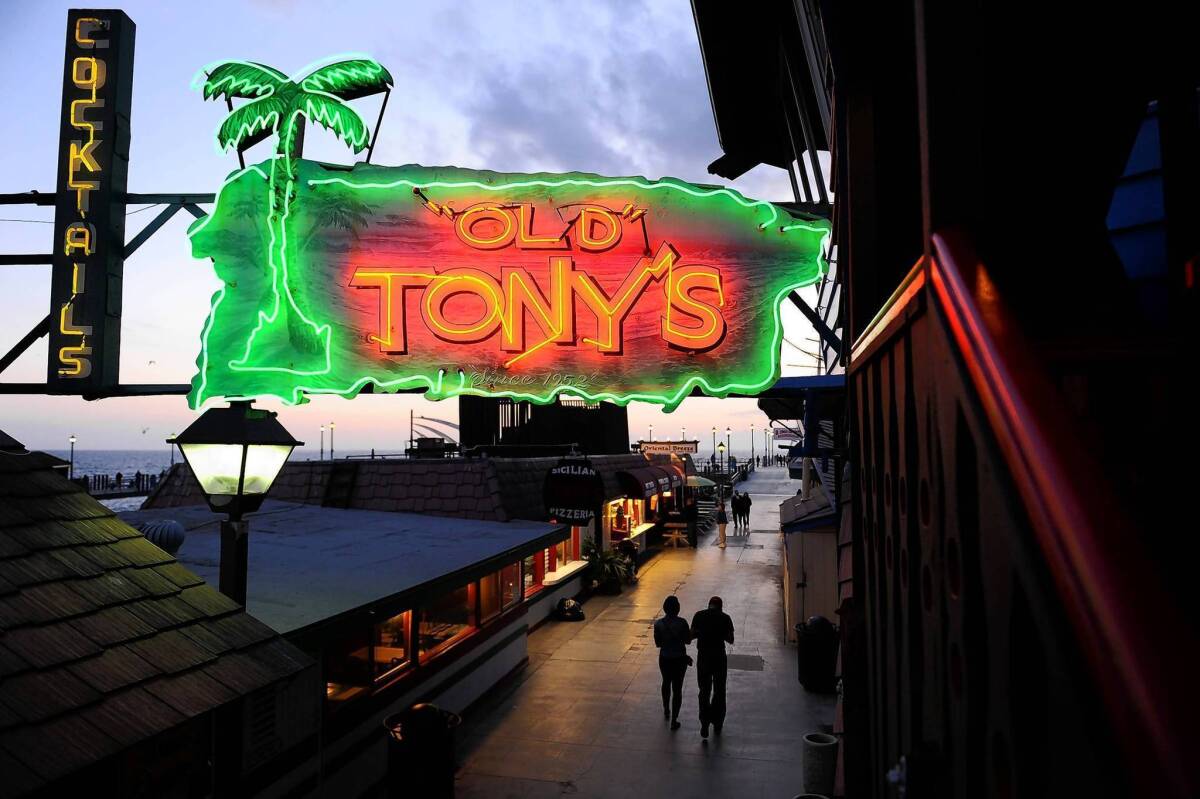

The dining room at Old Tony’s is a testament to its status as a survivor. Its aging green carpets and tan leather booths have overlooked Redondo Beach Pier for more than 60 years.

Inside, not much has changed.

The tiki bar and musty-gray fishing nets hanging from the ceiling are the kitsch of decades past, and some of the waitresses have been around since the Nixon administration.

In its heyday, throngs of visitors packed the pier, even on weekdays, catching movies at the stately Fox theater or fishing off the horseshoe-shaped pier. Business was brisk enough to support a second restaurant, Tony’s Fish Market, and still, dinner waits on a Saturday stretched into the hours.

“You saw kids running around with their cotton candy and ice cream till late at night. It was always so busy and alive,” says Michael Trutanich, whose father, Tony, opened the popular restaurant in 1952 that still serves as the pier’s anchor tenant.

These days, though, the crowds have thinned. After a devastating fire in 1988, many of the businesses closed; some that remain don’t even bother to open on cloudy days.

Now, after two decades of stagnation, Redondo Beach is on the move with a $300-million plan to redevelop the ailing waterfront district. Where there are now dated office buildings and T-shirt shops, developers envision a boutique hotel, green space and a San Francisco-inspired market hall.

But wary of the legacy of unfulfilled promises and development blunders, they are proceeding with caution. The last major effort to revitalize the area was abandoned amid protest from locals who hold a fierce loyalty for a place once considered the jewel of the South Bay.

Fred Bruning, chief executive of Centercal Properties, the developer the city has chosen to spearhead the new project, is a longtime South Bay resident and has his own childhood memories of fishing on the pier. He said he wants to restore it to its former glory.

“There’s got to be a bit of that majesty, that magic that used to be on the waterfront,” he said.

::

Today, the tired facades and crumbling asphalt along the International Boardwalk offer few clues of Redondo pier’s past glamour.

After abandoning its ambitions as a deep-water port in the late 1800s, Redondo Beach remade itself into a premier resort destination — “The Gem of the Continent,” proclaimed an advertisement that ran in the Los Angeles Times in 1881.

The iconic red cars carried beachgoers from downtown Los Angeles. Parasol-toting ladies strolled the waterfront’s “endless pier” or bathed in what was billed as the world’s largest saltwater plunge. Some tried their nerves on the Lightning Racer, a massive wooden roller coaster that towered above the sand.

But lightning-stoked fires and savage storms routinely battered the seaside resort, scattering pier lumber like matchsticks.

A black-and-white photo hangs over a table at Old Tony’s, depicting the toll of the winter of 1915. “Citizens worked all night Jan. 7th to rebuild sea wall,” the caption reads, “which was promptly washed out Jan. 10th.”

In 1988, a fierce winter storm and subsequent fire reduced a third of the businesses to ash.

“All of this was gone,” says Trutanich, looking toward the pier. It took six years to repair the damage and, he says, remaining storefronts were left to languish.

The man-made disasters haven’t helped matters.

Seeking a way to finance construction of the adjacent King Harbor, the city auctioned off control of the pier into separate leases. Owners had little incentive to make piecemeal investments on their own plots without knowing their neighbors’ intentions.

Then in the 1970s, Redondo razed its downtown to make room for high-rise condominiums, choking off direct access to the pier.

Some say it destroyed the soul of the city.

::

Bruning is determined to bring back the glory days. He talks about the pier as if it were an old friend and uses words like “authentic,” “history” and “sacred” when he mentions the waterfront.

His approach is not only sentimental but shrewd. Like many people here, he knows that the last attempt to remake the pier prompted a citizen’s revolt that had a rippling effect in the community for years.

Known as Heart of the City, the effort began to sputter when residents balked at the size and density of the development, which would have allowed as many as 3,000 new homes and 15 acres of commercial space along the waterfront.

When the city tried to move forward, volunteers in 2002 gathered thousands of signatures hoping to force a vote on the issue. Instead, city leaders abandoned the project, but voters went on to adopt measures that placed strict guidelines on future waterfront development and required voters to approve most zoning changes.

More than a decade later, some residents still express bitterness about the episode.

During Bruning’s first public meetings, many seemed fearful and suspicious of Centercal’s efforts.

But Bruning has made believers of some skeptics. Nadine Meissner, who lives in a waterfront condo and founded a group called Residents for Appropriate Development, says she was impressed by Centercal’s extensive engagement efforts.

“I think that Centercal has done a better job … about actually listening to the community and trying to handle some of the discontent up front,” said Meissner, who helped collect signatures 11 years ago for the citywide referendum. Meissner still has concerns about the density of the final project but so far is encouraged.

Nearly 200 residents attended a recent meeting, where they huddled around tables in groups of 10 to brainstorm ideas for architecture they’d like to see incorporated in the project. Others perused posters filled with photos of streetscapes and famous buildings, placing red stickers on examples they liked best.

The theme of the meeting, like all of the others, was inclusion and collaboration. But Bruning is clear that he wants to rethink much of the beloved landmark.

Although the concrete pier itself will remain intact, Bruning says, most of the buildings will need to be demolished and rebuilt to make way for upscale retailers such as Lululemon or a boutique movie theater.

Bruning also hopes to improve Seaside Lagoon, a sandy bowl near the harbor where children play on slides and under waterfalls in the summer months when the city pipes in water from the nearby power plant. Instead, Bruning hopes to open the lagoon to the ocean.

The city will also have to tackle such thorny issues as how to phase the construction to minimize its effects on local businesses, whether it can acquire federal or state grants to help with some of the cost, and how rents for longtime businesses will be affected.

The City Council expects to vote on a finalized plan in late July and proceed with the environmental review later.

Judy Milner, who has run various shops on the pier since 1972 and lost four retail stores in the fire, says she’s hopeful the project will succeed, despite the challenges. As with Old Tony’s, she was put on a tenuous month-to-month lease when the city began its revitalization campaign.

“I think the plan, overall, is good for the city. And I love this city. I love the pier,” Milner says. But, she adds, “personally, it’s a very insecure situation.”

Others chafe at the idea of change, or the thought that the pier’s old-school grit might be erased.

Ginny Mott, 48, a massage therapist, remembers celebrating her 16th birthday at Old Tony’s and cycling along the Esplanade. She recently moved back to Redondo and took comfort in the fact that much of the pier looked the same.

“I don’t want them to upgrade it anymore,” said Mott as she stood over her pink cruiser bicycle, dipping her Hot Dog on a Stick in bright yellow mustard.

Pat Aust disagrees.

“The sad part is living through all that degeneration,” says Aust, a current councilman who was the city’s fire chief the night flames engulfed the pier.

“This was the heart of the city, and now we need a transplant.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.