Barry Bonds steroid case goes to trial

Capping a national scandal over steroid use among star athletes, home run king Barry Bonds goes to trial Monday, accused of lying under oath in a case that will include big-name ballplayers and an ex-mistress ready to testify about Bonds’ sexual ineptitude.

The federal trial comes almost a decade after the start of a probe that sparked hearings before Congress, exposed the secret use of performance-enhancing drugs by many of the nation’s most admired athletes and forced professional sports to grapple with reforms.

“This is the final act,” said Golden Gate University Law School professor Peter Keane. “And Bonds is the big trophy.”

Prosecutors will try to prove that Bonds, 46, lied when he told a grand jury in 2003 that he had never knowingly used steroids.

The outcome may determine whether the years and money spent to snare the former San Francisco Giant amounted to an overreaching prosecution or the vindication of a search for justice and affirmation of the rule of law.

Kimberly Bell, a former model who had a long affair with Bonds, is the government’s star witness.

She is slated to testify that steroids diminished his sexual performance, shriveled his testicles and fired his temper. Bell has said that Bonds, jealous and annoyed when Mark McGwire broke the record in 1998 for most home runs in a single season, began taking steroids around 2000.

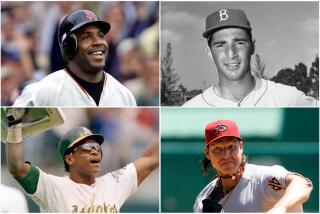

The next year Bonds topped McGwire’s single-season record with 73 home runs. His career record stands at 762, surpassing Hank Aaron and Babe Ruth.

Bell, whom Bonds helped support financially, will not be permitted to repeat her claim that Bonds once choked her in a rage, nor will the prosecution be able to play profanity-filled voicemails in which Bonds called her a slut.

U.S. District Judge Susan Illston, who is presiding over the case, also has barred defense lawyers from showing the jury a Playboy spread Bell did after her tempestuous split from Bonds.

Bonds’ trial culminates an era that saw the reputations of some of the nation’s top athletes tarnished by steroid disclosures. World records were expunged, and the U.S. had to give up Olympic medals. Sprinter Marion Jones went to prison.

Baseball was especially rocked. McGwire admitted steroid use last year, and Yankees slugger Alex Rodriguez also disclosed that he took steroids. His former teammate Roger Clemens, considered one of baseball’s greatest pitchers, stands accused of lying to Congress when denying steroid use. Clemens’ trial in federal court is scheduled for this summer.

The Colorado Rockies’ Jason Giambi and other baseball players are expected to testify they received performance-enhancing drugs from Bonds’ beleaguered but loyal former trainer, Greg Anderson. Prosecutors contend that Anderson, who has known Bonds since childhood, supplied him with steroids.

The three-week trial here is expected to open with the jailing of Anderson for refusing to testify. The convicted steroids dealer already has served nearly two years in prison, most of it because he would not implicate Bonds.

By contrast, many legal analysts expect Bonds to be sentenced to house arrest if convicted because Illston gave cyclist Tammy Thomas six months at home in 2008 for felony convictions of lying to a grand jury about steroids. Bonds lives in a villa in Beverly Hills.

Keane, the Golden Gate University professor and a former criminal defense lawyer, has a different view. He said he would “bet on” prison for Bonds. “He is such a big fish, and lying before a grand jury is considered such a serious crime in the justice system,” he said.

Perjury can be hard to prove, despite the high-profile convictions of Martha Stewart for lying to investigators and of Scooter Libby, the White House aide who lied under oath.

Bonds’ prosecution also has been hobbled by a ruling that barred evidence of private laboratory records showing Bonds testing positive for steroids in 2000, 2001 and 2002.

Illston said the government could not prove that the samples came from Bonds without the testimony of Anderson, who allegedly took them from Bonds to the lab.

Major league baseball did not test for steroids during the early 2000s or even inquire about their use. Baseball first began anonymous screening of players in 2003 but did not penalize players who tested positive. Mandatory testing for all players began in 2004, and the league stiffened penalties for players under a formal steroid ban in 2005.

Investigators seized Bonds’ 2003 league sample, and further testing found it to be positive for a steroid and other drugs, a government witness will tell the jury.

The jury also is expected to hear an ex-teammate’s claim that Bonds told him he took steroids, a tape-recording of Anderson implying that he had injected Bonds and testimony from Bonds’ formal personal shopper, who said she saw Anderson inject Bonds in the navel.

Bonds told the grand jury, assigned to investigate a Bay Area laboratory, that Anderson never injected him. The slugger also maintained that he began using substances he thought were flax seed oil and arthritis balm during the 2003 season.

Keane said the prosecution’s witnesses and the physical changes in Bonds — “he went from lanky to become Bluto in such a short time and had a remarkable performance late in life” — were enough to prove “slam dunk” that Bonds lied under oath.

But Robert Talbot, professor at the University of San Francisco School of Law, who teaches federal rules of evidence, said jurors will be instructed that testimony is relevant only for certain purposes, limiting its value to the prosecution.

“The evidence is not right on the money,” Talbot said.

Prosecutors have expressed concerns that jurors might ignore the law and try to send a message to the government by finding Bonds not guilty. The Giants won the World Series last year and Bonds, let go by the team in 2007, remains popular with many fans. His late father, Bobby Bonds, also was a Giants star.

Federal law requires prosecutors to prove that Bonds consciously and willfully lied under oath. It is not enough if jurors believe Bonds may simply have misunderstood questions or relied on a faulty memory, Talbot said.

Even if key evidence had not been excluded, “it would have been an uphill battle to get a unanimous jury in San Francisco to find Barry Bonds guilty,” Talbot said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.