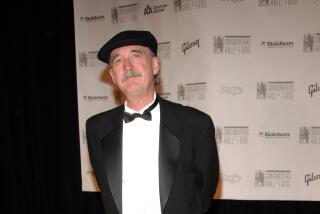

Eddy Arnold, 89; country music’s all-time hit maker

Eddy Arnold, the most successful country hit maker of all time, who played a crucial role in transforming what had long been considered “hillbilly music” from a rural phenomenon into music with broad-based national appeal, died Thursday. He was 89, a week short of his 90th birthday.

Arnold, an elegant, pop-influenced singer, died at a long-term care facility near Nashville, family spokesman and Arnold biographer Don Cusic said Thursday. His wife of 66 years, Sally, had died in March and Arnold had broken his hip the same month in a fall at his home.

Determined throughout his life to transcend the rural poverty he had known as a child in Tennessee, he carved out an identity as an urbane crooner unrestricted by the trappings associated with country music stardom. He has been called “the Garth Brooks of his time” for creating the template still followed today by country singers who reach beyond a niche audience to capture a broad following, a move that angered many traditional country fans.

“He epitomized how someone could become a huge star in this genre,” Kyle Young, director of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, said Thursday. “He certainly set the bar: He sold 80 million records, had his own TV show, filled in for Johnny Carson as a ‘Tonight Show’ host. In some ways his career defines what it’s like to end up at the top of the heap.”

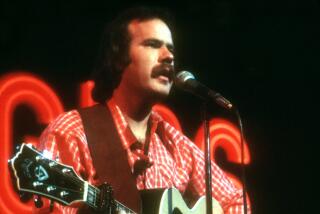

Arnold had a nine-year run of 57 consecutive top 10 hits from 1945 to 1954, among them “I’ll Hold You in My Heart (Till I Can Hold You in My Arms),” which spent more than five months at No. 1 in 1947, and “Bouquet of Roses,” which logged 19 weeks in the top spot the following year. Many of those songs, despite the twangy steel guitars and fiddles under his voice, appealed to large numbers of fans because of his mellow tenor, which was virtually free of a drawl.

“More than anyone in the 1940s, he helped change the image of the music from ‘hillbilly’ to ‘country,’ ” Robert Hilburn, The Times’ former pop music critic, said Thursday. “He ranks with Johnny Cash as one of the great ambassadors of country music.”

Arnold’s music had a huge effect on succeeding generations of country performers.

“When I was about 15 years old, the only stuff I sang was Eddy Arnold,” George Jones said in a statement Thursday. “He would be just about my whole show. I’d sing ‘Bouquet of Roses’ and ‘I’m Throwing Rice (at the Girl I Love).’ All I sang was Eddy until I heard Hank Williams.”

And Arnold acted as a mentor for countless younger singers.

“He’s given me a lot of advice,” singer Josh Turner wrote in the liner notes for his 2006 album “Your Man,” which reached No. 2 on Billboard’s overall album chart, “but the one thing that stuck out in my mind when it came to making this record was when he told me, ‘You go and record some love songs, because that’s what people relate to.’ He said, ‘The relationship between a woman and a man relates to people better than anything else.’ ”

Although Arnold’s popularity dipped for a time in the late 1950s in the wake of rock ‘n’ roll’s arrival, it rebounded in the 1960s, after a crucial change in the people guiding him musically and professionally. That led to another run of hits that crystallized what became known as “the Nashville Sound,” typified by swelling orchestral backgrounds and female choir voices behind songs such as “Make the World Go Away” and “I Want to Go With You,” both No. 1 country hits.

“He always had a sense that his voice could carry him into the pop market,” said Michael Streissguth, author of the 1997 biography “Eddy Arnold: Pioneer of the Nashville Sound.” “It really was a vision that he had of where his career could go.”

Arnold’s career spanned seven decades, from the 1930s, when he hosted a radio show for five years in Memphis, Tenn., until 1999, when he last appeared on the country singles chart with a duet with then-teenage singer LeAnn Rimes in a new version of his 1955 yodel-laden western hit “Cattle Call.”

“I don’t know that that will ever happen again,” Young said. “Think of it: 80 million records sold. That’s a number that compares to Garth Brooks’ total. He was the Garth Brooks, the Kenny Chesney of his time, and his time spanned many years.”

In the latest edition of Joel Whitburn’s “Top Country Songs” volume collating Billboard’s charts from 1944 to 2005, Arnold is ranked as the No. 1 country artist of all time, logging 146 records in the Top 100 of Billboard’s country singles chart, 28 of those making it to No. 1.

Richard Edward Arnold, who was born May 15, 1918, in Henderson, Tenn., grew up working on his parents’ farm, only to see it repossessed during the Depression, after which the family became sharecroppers on what had been their own land.

His father died when Eddy was 11, so the boy started singing at church picnics and other events, sometimes earning $1 a gig.

“His childhood made such an impression on him,” Country Hall of Fame’s Young said. “I would say he was driven, probably until his last breath, because he was still worried that some day he might wake up penniless.”

As a boy he idolized “the Singing Cowboy,” Gene Autry, as well as Bing Crosby, whose smooth, outwardly effortless style he would later emulate.

He landed a regular role on a radio show at WTJS in Memphis, and in 1940 was hired as a singer for Pee Wee King and His Golden West Cowboys, which had a reputation for a more debonair brand of country dance music and was featured frequently on the Grand Ole Opry broadcasts.

Arnold was hired by the Opry as a solo performer in 1943. Early on he had been dubbed “the Tennessee Plowboy” and at first his recordings sounded in many ways like other country acts. The difference was Arnold’s voice, which had more in common with the easygoing delivery of Autry and Crosby.

When he signed with Victor Records (which became RCA) and began his recording career, he was managed by Col. Tom Parker, who would later become Elvis Presley’s manager. “All the things Parker did with Elvis,” biographer Cusic said Thursday, “he got all those contacts from working with Eddy.”

When television arrived, Arnold was virtually the only country performer who began appearing regularly on national programs with Milton Berle, Arthur Godfrey and later Ed Sullivan. He also performed in Las Vegas showrooms before nearly any other country act.

After Arnold fired Parker, he signed with a fledgling New York-based management company that strove to de-emphasize the bumpkin image often foisted upon him in those forums.

When that company folded in the 1960s, he hired an ex-Mafia figure, Gerald Purcell, who insisted that he only appear on television and on stage in a tuxedo, and refused to allow fiddles or steel guitars on his records, solidifying his complete break with Nashville tradition.

At the same time, he had returned to Nashville after recording with less success in New York. He connected with Chet Atkins, one of RCA’s leading country producers, who shepherded him into “the Nashville Sound” style that had been working magic in the ‘50s for fellow country crooner Jim Reeves.

Reeves’ death in 1964 in a plane crash opened a door for Arnold. Reeves’ arranger, Bill Walker, gravitated to Arnold, and their collaboration resulted in the mid-1960s hits that revitalized his career.

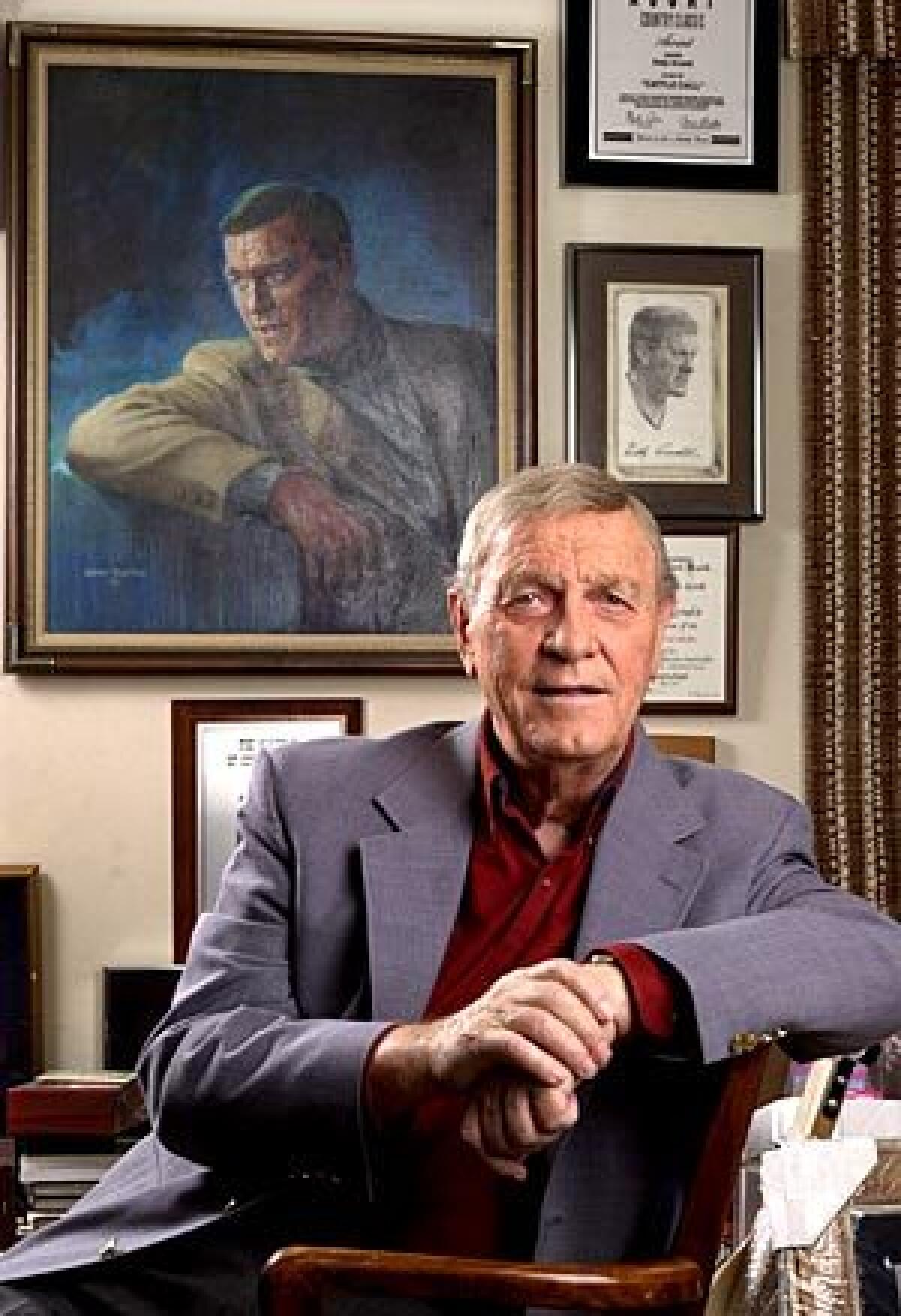

Where other country stars flashed their success with bejeweled cowboy outfits, silver-dollar-covered luxury cars and guitar-shaped swimming pools, Arnold remained the low-key country gentleman, quietly parlaying the money from his hit records into lucrative real estate investments in and around Nashville.

“He was often called the wealthiest man in Nashville,” Streissguth said.

But you would never know it from outward appearances.

Critic Hilburn offered similar memories of Arnold: “He was a humble guy who didn’t seem to care all that much about the razzle-dazzle surrounding the music business. He was just into going onstage, or into the studio, and singing his songs and then enjoying his hobbies and private life.”

Arnold is survived by his son, Richard Edward Arnold Jr., and daughter, Jo Ann Pollard, as well as two grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. Visitation will take place Tuesday evening and Wednesday morning at the Country Music Hall of Fame, followed Wednesday afternoon by a funeral at the Ryman Auditorium, the longtime home of the Grand Ole Opry.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.