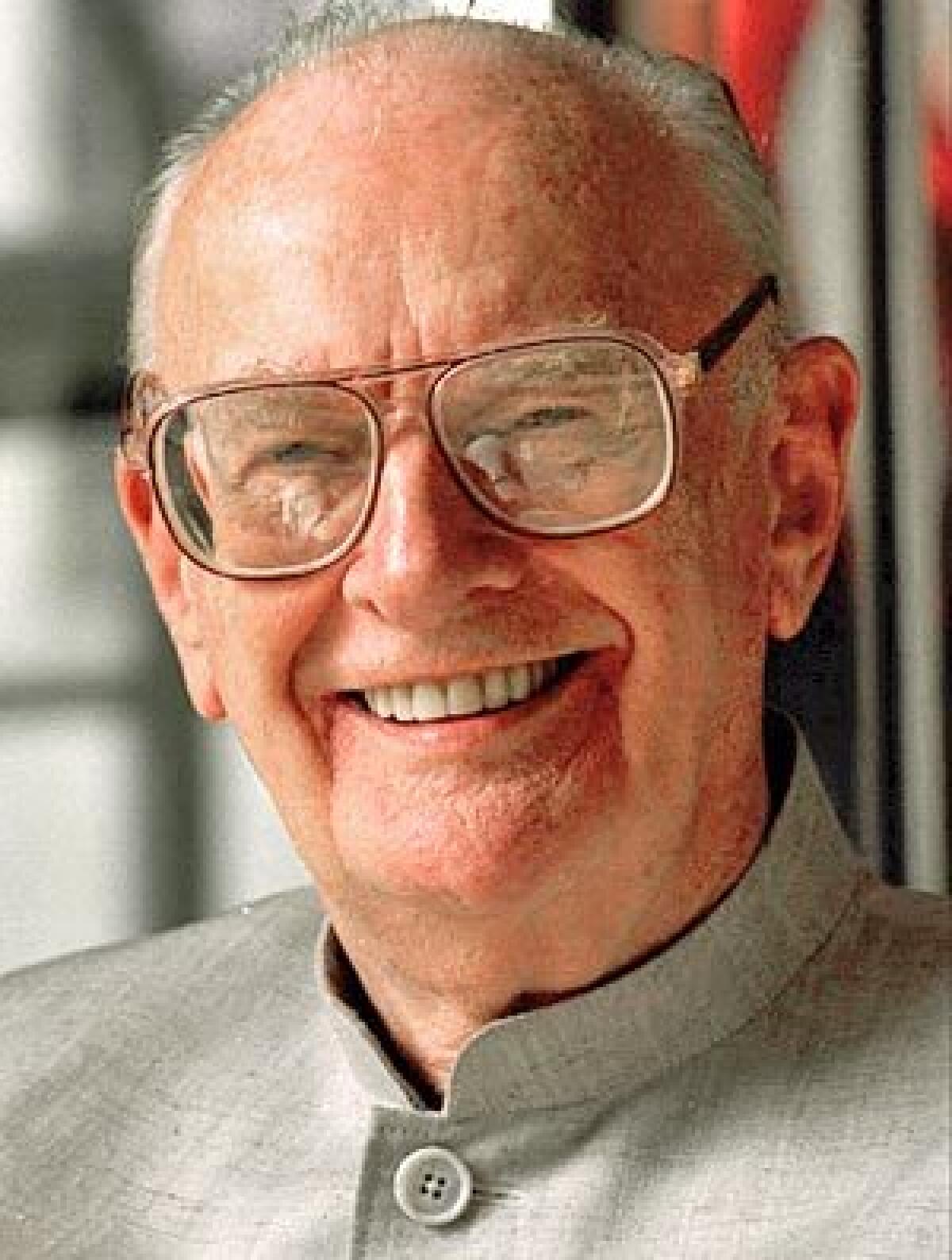

Arthur C. Clarke, 90; scientific visionary, acclaimed writer of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’

Arthur C. Clarke, who peered into the heavens with a homemade telescope as a boy and grew up to become a visionary titan of science-fiction writing and collaborated with director Stanley Kubrick on the landmark film “2001: A Space Odyssey,” has died. He was 90.

The knighted British-born writer died early Wednesday in Colombo, Sri Lanka, where he had made his home for decades, after experiencing a cardio-respiratory attack, his secretary, Rohan De Silva, told Reuters.

Clarke wrote scores of fiction and nonfiction books (some in collaboration) and more than 100 short stories -- as well as hundreds of articles and essays. Among his best-known science-fiction novels are “Childhood’s End,” “Rendezvous With Rama,” “Imperial Earth” and “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

Deemed a scientific prophet, Clarke foretold an array of technological notions in his works such as space stations, moon landings using a mother ship and a landing pod, cellular phones and the Internet.

“Nobody has done more in the way of enlightened prediction,” science-fiction author Isaac Asimov once wrote.

“I’d say he was the major hard science-fiction writer -- that is, the writer of science fiction that is scientifically scrupulous -- in the second half of the 20th century,” UC Irvine physics professor Gregory Benford, an award-winning science-fiction author who collaborated with Clarke on the 1990 science-fiction novel “Beyond the Fall of Night,” told The Times in 2005.

George Slusser, author of the 1978 book “The Space Odysseys of Arthur C. Clarke” and curator emeritus of UC Riverside’s Eaton Collection -- the world’s largest publicly accessible collection of science fiction, fantasy, horror and utopian fiction -- ranks Clarke as one of the three greatest science-fiction writers of all time.

“Clarke, along with Asimov and [ Robert A.] Heinlein, is unique in that his human dramas are determined by advances in science and technology,” Slusser, a professor of comparative literature, said in 2005. “He places his characters in a near future where science has changed the way we live and the possibilities for adventure.

“Clarke incarnates the essence of [science fiction], which is to blend two otherwise opposite activities into a single story, that of the advancement of mankind.”

His remarkable record of foreseeing future technologies led him to be known as “the godfather of the telecommunications satellite.”

A radar pioneer in the Royal Air Force during World War II, Clarke wrote a 1945 article in Wireless World magazine in which he outlined a worldwide communications network based on fixed satellites orbiting Earth at an altitude of 22,300 miles -- an orbital area now often referred to as the Clarke Orbit.

Clarke’s seminal article, for which he received $40, was published two decades before Syncom II became the world’s first communications satellite put into geosynchronous orbit in 1963.

For pioneering the concept of communications satellites, Clarke received a number of honors, including the 1982 Marconi International Fellowship and the Charles A. Lindbergh Award.

His literary career soared with the success of his 1951 nonfiction book “The Exploration of Space” and his critically acclaimed 1953 science-fiction classic “Childhood’s End.”

“Rendezvous with Rama,” his 1973 novel about a space probe sent to explore an enormous celestial object speeding through the solar system that turns out to be a mysterious alien spacecraft, was one of Clarke’s greatest critical successes.

It won the prestigious Nebula, Hugo and John W. Campbell awards for best novel, as well as the British Science Fiction Associate Award, the Locus Award and the Jupiter Award.

His collaboration with Kubrick to create a work about man’s place in the universe began in 1964 when he was in New York City to complete his work on the Time/Life book “Man and Space.”

“What I want,” Kubrick repeatedly told Clarke, “is a theme of mythic grandeur.”

Inspired in part by Clarke’s short story “The Sentinel,” about the discovery of an alien artifact on the moon, the two men began their collaboration with weeks of brainstorming sessions.

“Perhaps because Stanley realized that I had low tolerance for boredom, he suggested that before we embarked on the drudgery of the script, we let our imaginations soar freely by writing a complete novel, from which we would later derive the script,” Clarke wrote in the foreword to the millennial edition of “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

“This is more or less the way it worked out, though toward the end, novel and screenplay were being written simultaneously, with feedback in both directions,” he wrote. “Thus I rewrote some sections after seeing the movie rushes -- a rather expensive method of literary creation, which few other authors can have enjoyed.”

Clarke’s “2001” novel was published a few months after the movie’s release in 1968.

“He has the kind of mind of which the world can never have enough, an array of imagination, intelligence, knowledge and a quirkish curiosity, which often uncovers more than the first three qualities,” Kubrick said at the time.

The film concerns the “Dawn of Man” and a mysterious black monolith and a mission to Jupiter with a deadly, on-board talking computer named HAL.

In the end, the sole-surviving astronaut is reborn as a glowing embryo with large, haunting eyes, orbiting Earth in a translucent placenta.

Though some critics complained about the special effects-laden movie’s slow pace, minimal dialogue and lack of plot and character development, most hailed it as a landmark film.

“2001” quickly became a must-see movie, particularly among young people who were entranced by the dazzling imagery. One 17-year-old high school student reportedly observed at the time: “You’re not supposed to understand it, you’re supposed to watch it!”

Clarke later relished telling the story of one visit to the United States when an immigration official looked at his passport and said, “I won’t let you in until you explain the ending of ‘2001.’ ”

In a 1982 interview with The Times, the author explained: “The theme of the book is, of course, evolution, from the ape-men you see at the beginning to [the astronaut’s] succession to a higher form of consciousness or intelligence, the star child.”

“2001: A Space Odyssey” earned Kubrick and Clarke an Oscar nomination for their screenplay and launched the already well-known Clarke to international acclaim as what one journalist called the unofficial “poet laureate of the Space Age.”

Although he never intended to write a sequel to “2001,” he wrote three: “2010: Odyssey Two,” “2061: Odyssey Three” and “3001: The Final Odyssey.”

Clarke’s celebrity status was further enhanced when he offered commentary alongside CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite during the Apollo missions.

He later wrote and hosted two television series for British television that were syndicated around the world in the 1980s, “Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World” and “Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers.”

The author, who had an asteroid and a joint Russian-European satellite named after him, enjoyed his celebrity. He counted heads of state and astronauts among his friends, and he was known to name-drop with what a British journalist called “a shamelessness that disarms criticism.”

Visitors to his home in an exclusive section of Colombo, the capital of Sri Lanka, were asked to wait in an anteroom to Clarke’s office, which was filled with photos, plaques and citations from NASA and other scientific and literary organizations.

Clarke called it his “Ego Chamber.”

Among his memorabilia: a moon rock given to him by NASA, a T-shirt signed by Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin and the opening page of a published lecture by fellow Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong on which the first man to walk on the moon wrote: “To Arthur -- who visualized the nuances of lunar flying before I experienced them.”

A large, craggy-faced man with tortoise-shell glasses, Clarke typically padded around his home wearing a patterned sarong and a cotton shirt.

Benford, the science-fiction author, who first met Clarke in 1979, described him as “always very friendly and outgoing, an English gentleman.”

During a visit to Clarke’s home in Sri Lanka in the ‘90s, Benford recalled: “He gave me his red Mercedes and driver to go around and see the sights. Everywhere we went people waved at the car thinking it was Arthur.”

The oldest of four children, Clarke was born in Minehead, England, on Dec. 16, 1917, and grew up on a farm in Somerset.

Initially drawn to dinosaurs and fossils as a boy, Clarke developed a fascination with astronomy and constructed several refractor telescopes in his early teens by inserting lenses into cardboard tubes.

He saw his first science-fiction magazine -- the November 1928 issue of Amazing Stories -- when he was 11. But it wasn’t until he read a copy of the March 1930 issue of Astounding Stories of Super-Science that, he later told biographer Neil McAleer, “My life was irrevocably changed.”

“Young readers of today, born into a world in which science-fiction magazines, books and movies are part of everyday life, cannot possibly imagine the impact such garish pulps as that old Amazing and its colleagues Astounding and Wonder” had, Clarke wrote in a 1983 article in the New York Times Book Review. “Of course, the literary standards were usually abysmal -- but the stories brimmed with ideas and amply evoked that sense of wonder that is, or should be, one of the goals of the best fiction.”

He began devouring books by H.G. Wells, Jules Verne, Olaf Stapledon and other authors and started writing short stories as a teenager for his school magazine.

Unable to afford college, Clarke took a civil service job as an auditor. In his off hours, he hung out with fellow science-fiction fans and members of the British Interplanetary Society, an organization devoted to supporting and promoting the exploration of space. Clarke later became the group’s treasurer and wrote its brochures.

Volunteering for the Royal Air Force during World War II, Clarke became a technical officer and was stationed at a radar installation.

While in the military, Clarke continued to write mostly nonfiction. He made his first professional fiction sale -- for $180 -- to Astounding Science Fiction, which in 1946 published “Recue Party,” a short story he had written while in the service.

After the war, Clarke studied physics and pure and applied mathematics at King’s College in London. He then spent two years as assistant editor for the journal Physics Abstracts and published many short science-fiction stories and scientific articles -- as well as a 1950 nonfiction book, “Interplanetary Flight,” which led to British television appearances to promote science and space exploration.

With the great success of his breakthrough 1951 popular science book “The Exploration of Space,” which earned him a sizable sum when it sold to the Book of the Month Club, Clarke began writing full time.

While on a research trip for a nonfiction book about Australia’s Great Barrier Reef in 1954, Clarke discovered the tropical island of Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, off the southern tip of India. He made it his home two years later.

In 1962, Clarke found himself paralyzed, according to McAleer’s 1992 book “Arthur C. Clarke: The Authorized Biography.” He spent six weeks in a hospital and eventually recovered. But in 1988, after finding it difficult to walk and tiring easily, Clarke was diagnosed with Post-Polio Syndrome.

He sometimes used a wheelchair but was still able to continue one of his lifelong passions: scuba diving, which first drew him to Sri Lanka, once noting that he was “perfectly operational underwater.”

In Sri Lanka, Clarke was isolated but not out of touch. He had half a dozen computers and remained in contact with friends, colleagues and fans via daily e-mails. And he dealt with a steady stream of journalists.

Clarke is said to have often ignored his own one-question rule and answered questions on a variety of topics, including extraterrestrials and UFOs.

“One thing is certain -- if extraterrestrial beings do visit our planet, they won’t be little green men,” he told the Sydney Daily Telegraph in 1997. “In fact, they won’t be human at all. So when someone says they’ve seen, let alone been kidnapped by, beings with a head, eyes, limbs and a body, I know they are deceiving themselves.

“They may believe it’s happening, but they are wrong. Look at the incredible variety of life forms on this planet -- yet all these extraterrestrials look like refugees from Central Casting.”

On his 90th birthday in December, he listed three wishes for the world, the Associated Press reported: to embrace cleaner energy resources, for a lasting peace in his homeland of Sri Lanka, which has been beset by civil strife for decades, and for evidence of extraterrestrial beings.

“Sometimes I am asked how I would like to be remembered,” Clarke said. “I have had a diverse career as a writer, underwater explorer and space promoter. Of all these I would like to be remembered as a writer.”

Clarke regretted never having made it to the moon, he once told the Associated Press, “but I feel I’ve gone into space so many times now.” With a shrug and a grin, he added: “You know -- been there, done that.”

Clarke’s 1953 marriage to Marilyn Torgerson, a divorced American with a young son, lasted about six months -- although it was not legally dissolved until 1964. He had no children.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.