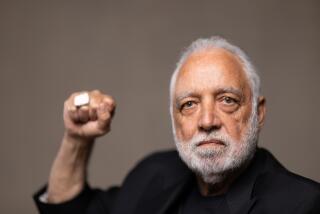

Charles Morgan Jr. dies at 78; lawyer challenged racism in the South

Charles Morgan Jr., a civil rights lawyer who challenged the racism of his native South and won numerous landmark cases for equal rights before the U.S. Supreme Court, died Thursday at his home in Destin, Fla. He was 78 and had Alzheimer’s disease.

In a career full of significant cases, Morgan’s most important triumph might have been the “one-man, one-vote” ruling he won in 1964 from the Supreme Court. The case, Reynolds vs. Sims, forced the Alabama Legislature to create districts that were equal in population, giving black voters a better chance to elect candidates.

He also forced Alabama to integrate its prisons, successfully challenged the Southern practice of barring women and blacks from jury duty and represented Julian Bond when the Georgia General Assembly tried to prevent the newly elected legislator from taking his seat after he spoke out against the Vietnam War.

“He was one of the most important people” in civil rights litigation, said Bond, now the chairman of the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People. “He did in the South through the courts what Martin Luther King did in the streets.”

The Reynolds case “ended gerrymandering,” said Richard Cohen, president of the Southern Poverty Law Center. “It was one of the seminal cases in the march for voting rights in this country and was the death knell for voting discrimination in the South. Chuck’s work in voting rights cases and jury discrimination cases changed the landscape of the South completely.”

Morgan, who opened the American Civil Liberties Union’s Atlanta office in 1964 and became legislative director of the ACLU’s national office in Washington in 1972, defended some of the most controversial cases of the 1960s and ‘70s. He successfully appealed to the Supreme Court the draft evasion conviction of heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali, who opposed the Vietnam War on religious grounds.

Morgan also represented a number of military clients, including an Army physician who refused to train Vietnam-bound Green Berets.

He sued to desegregate his alma mater, the University of Alabama, unsuccessfully sued to overturn the 1966 Georgia gubernatorial election and successfully forced a new election in Greene County, Ala., that led to the 1969 election of six black candidates for local offices.

“I love the Constitution, I love the law, and I have no dislike at all for Southern rednecks, some of my ancestors having been among them,” Morgan told New Yorker magazine in 1969.

In 1977, he left the ACLU to go into private practice. The lawyer who sued over the federal wiretapping of liberals and led an early movement to impeach President Nixon astounded his friends by representing John N. Mitchell, a Nixon advisor and former attorney general, in an unsuccessful attempt to shorten his prison term. He also represented the Tobacco Institute in a fight against a municipal ordinance banning smoking in public places and corporate clients accused of discrimination.

Morgan unsuccessfully defended before the Supreme Court an influential Atlanta law firm that promoted male associates faster than female associates. He won a series of major cases for Sears, Roebuck and Co. over allegations of race and sex discrimination brought by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

He was born March 11, 1930, in Cincinnati. He graduated from the University of Alabama, where he also received a law degree in 1955.

Early in his career, he publicly deplored racial injustice and represented indigent blacks at no cost in his spare time while working at a corporate law firm in Birmingham. Then, in September 1963, the day after four young black girls died in the firebombing of Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, Morgan took the podium at the Young Men’s Business Club.

“We are a mass of intolerance and bigotry, and stand indicted before our young,” he said. “We are cursed by the failure of each of us to accept responsibility, by our defense of an already dead institution. . . . Every person in this community who has in any way contributed during the past several years to the popularity of hatred is at least as guilty as the demented fool who threw the bomb.

“Who did it? Who threw that bomb? The answer should be, ‘We all did it.’ ”

The community reaction was swift and brutal. Crosses were burned on his lawn, polite society shunned him, and he received anonymous death threats. He eventually moved his family out of the city.

He had worked briefly for the NAACP and the American Assn. of University Professors before joining the ACLU in 1964.

He wrote “A Time to Speak” (1964) about his early years and “One Man, One Voice” (1979) about his experiences from 1964 to 1976.

Survivors include his wife of 55 years, Camille Walpole Morgan; a son, Charles Morgan III of Destin; and four grandchildren.

Sullivan writes for the Washington Post.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.