Why print survives

- Share via

We are told with numbing regularity these days that “print is dead” and that the Digital Age soon will sweep the bound, mass-produced book into history’s bin of extinct curiosities alongside species once similarly numerous, like the woolly mammoth and the passenger pigeon.

We will receive our wisdom, information and literary entertainment not from printed pages but in recovered pulses of code. This is to be the e-book epoch, the era of the Kindle.

What does it signify, then, that in London this week, an auction at Sotheby’s achieved a record price for a printed book — $11.5 million for a copy of John James Audubon’s great four-volume “Birds of America”? Is print’s demise exaggerated, or does the elevation of books to precious objects simply announce the decadence of publishing as we’ve known it?

Yes and yes, but …

First of all, there’s both more and slightly less to this particular transaction than meets the eye. The successful bidder, 66-year-old London art dealer Michael Tollemache, is simultaneously a connoisseur of the visual arts, a passionate bibliophile and a lifelong bird watcher. Audubon’s great work, with its 435 astonishingly beautiful and precise hand-colored engravings, is a landmark in all three fields, perhaps the chief ornament of 19th century printing in the West. The book’s visual impact derives in part from its oversized folio format — “double elephant” in the printing trade — which means each volume is 4 feet wide when open. The precision of Audubon’s observation and his attention to sound taxonomy make “Birds of America” an ornithological enthusiast’s delight, which is why this country’s leading organization concerned with the conservation of birds and their habitat took his name as its own.

From the start, his masterwork was intended for the wealthy. Audubon was an immigrant, born to a sugar planter and privateer in Haiti and raised in France. America, where his father sent him to manage a farm and lead mine, and its wildlife, particularly birds, became his passion. But when he came to publish his great collection of paintings and field observations, no U.S. printer was up to the job. So, in 1838 he spent an astonishing — for the time — $115,000 at a London printer and engraver and sold the 160-plus copies of the book to subscribers for the princely sum of $1,000 each. Ten years ago, another copy set the previous record price for a printed book — $8.8 million paid by another passionate birder, Sheik Saud bin Mohammad bin Ali al Thani of Qatar. What’s interesting about those prices is that Audubon’s masterpiece isn’t a particularly rare book; 119 copies survive, and Christie’s will auction another in New York next month.

What, then, about the e-book? The online retailer Amazon.com now sells more of them than it does hardbacks. Though 90% of all book sales still involve conventionally printed volumes, e-book sales doubled last year to $340 million. Some retail analysts project that over this holiday buying season, only smartphones will outsell Kindles among high-end “personal appliances.”

As the Wall Street Journal reported this week, Leonard Riggio, who runs Barnes & Noble, recently said that “digital publishing and digital bookselling will soon become the most explosive development in the history of our industry and will sweep aside those who aren’t participating.”

Maybe — or maybe it will just sweep aside the corporate concerns that arose during this anomalous era in which conglomerates gobbled up individual publishing houses, obliterated their distinctive characters, treated books like films or wildcat oil wells and paid a handful of superstar authors like movie stars. If that perfectly legitimate but not particularly edifying end of the business moves to digital formats for economic reasons, not much has been lost.

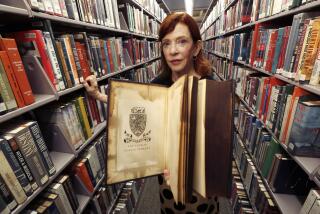

As Andrew Pettegree points out in his marvelous “The Book in the Renaissance,” from its outset publishing has been a chaotic and economically grinding undertaking. Gutenberg himself died impoverished, and 60 years after his epochal invention of movable type, literate European aristocrats still were ordering hand-illuminated manuscripts for their libraries. In the 1470s, the influential Benedictine Filippo de Strata urged the Doge of Venice — then Europe’s publishing center — to ban all printing because it subverted the true appreciation of letters. For decades to come, bibliophiles and keepers of libraries would actually have handwritten copies of printed books made for their collections.

The e-book will find its place and print will survive.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.