Can a high school paper nix the name ‘Redskins’?

A long time ago, I was an editor on my high school paper and something of a troublemaker. So I have some sympathy for the editors of the student newspaper at Neshaminy High School in eastern Pennsylvania. On Tuesday, the editors will meet with the school principal to address a controversy over the paper’s decision to refrain from printing the name of the school’s sports teams, which happens to be the same as Washington’s NFL team: the Redskins.

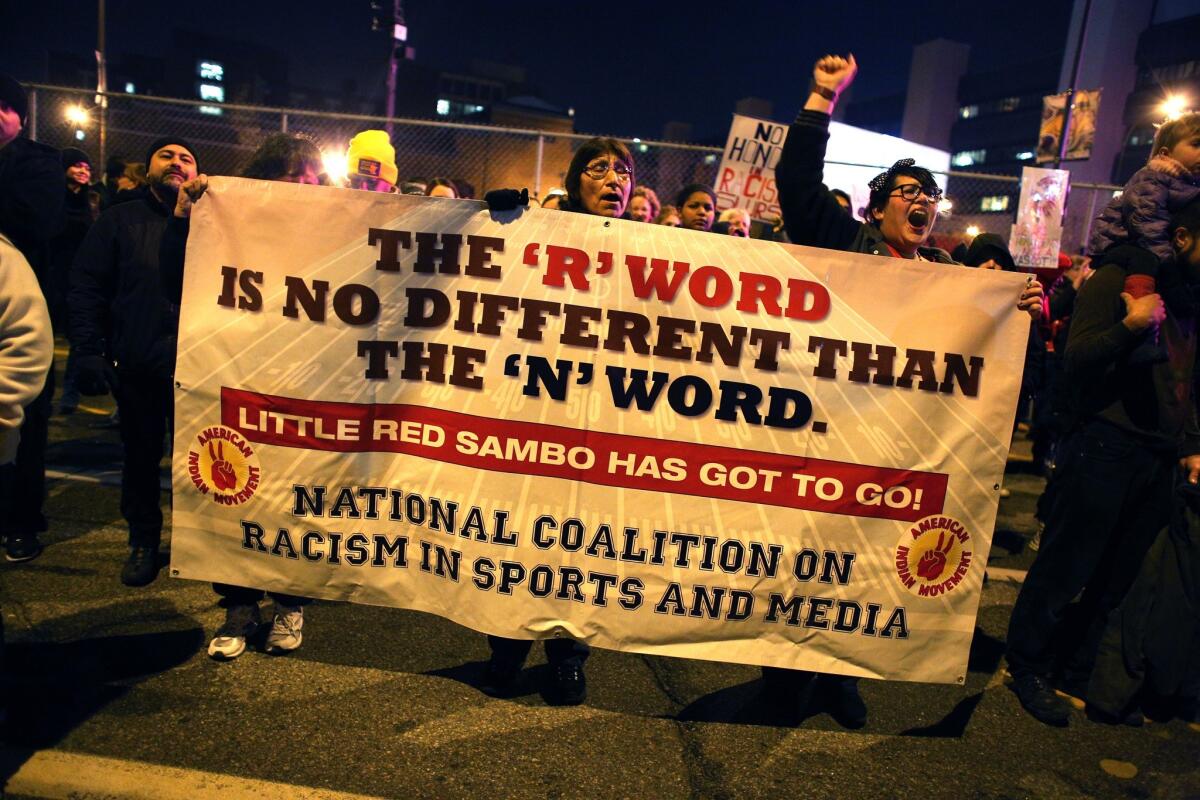

An editorial announcing the change said the team name was “not a term of honor but a term of hate.” It added: “Detractors will argue that the word is used with all due respect. But the offensiveness of a word cannot be judged by its intended meaning but by how it is received.” Therefore, “Redskins” would be banned from the paper, which is called the Playwickian. (Talk about questionable names.)

The young editors attracted cheers from advocates of frisky student journalism. But the school’s principal, Robert McGee, wasn’t pleased. “I don’t think that’s been decided at the national level, whether that word is or is not (offensive),” McGee said. “It’s our school mascot.” McGee, who said he had consulted with the school solicitor, added: “I see it as a 1st Amendment issue running into another 1st Amendment issue.”

Despite my identification with the upstart editors, my reading on the 1st Amendment issue favors the school. In 1988, in Hazelwood School District vs. Kuhlmeier, the Supreme Court drew a distinction between an individual student’s right of free speech and the contents of a school newspaper. The latter issue, Justice Byron White wrote, “concerns educators’ authority over school-sponsored publications, theatrical productions and other expressive activities that students, parents and members of the public might reasonably perceive to bear the imprimatur of the school.”

Put another way, the principal is the publisher of the student paper, and as “real life” journalists know, the publisher has the final word.

The Student Press Law Center, an admirable organization, suggests that the student editors at Neshaminy High might derive some additional protection from the Pennsylvania school code. One section of that document says that students “have a right and are as free as editors of other newspapers to report the news and to editorialize.” Another warns that school officials “may not censor or restrict material simply because it is critical of the school or its administration.”

But — surprise, surprise — editors of school newspapers in Pennsylvania are subject to conditions that don’t restrict their professional counterparts. For example, the code says that school officials “may edit other material that would cause … interference with school activities.” One such activity is to encourage support for the school’s teams; in fact, according to USA Today, the welcome sign at the school sometimes reads “Everybody do the Redskin Rumble.”

Frank LoMonte, executive director of the Student Press Law Center, told USA Today that he understood that “there’s an inclination to want to protect a tradition at the school.” But he said that “the 1st Amendment is a longer and a better-established tradition.”

Except that there is no tradition that the 1st Amendment protects student papers at public high schools in exactly the way it protects “real” newspapers. As the Supreme Court said in Hazelwood (quoting another decision): “We have nonetheless recognized that the 1st Amendment rights of students in the public schools ‘are not automatically coextensive with the rights of adults in other settings.’ ”

That’s also an important lesson for the editors of the Playwickian to learn.

ALSO:

McManus: JFK, a presidency on a pedestal

Typhoon Haiyan and the language of disaster

Esperanza Spalding: Music to shine a light on Guantanamo Bay

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.