India introduces, then quickly cancels, a plan to blacklist reporters for spreading ‘fake news’

The Indian government on Tuesday abruptly withdrew a plan to blacklist journalists for spreading “fake news,” after an outcry from reporters who said it would muzzle the press ahead of national elections next year.

The measure announced Monday night would have stripped any print or television journalist accused of having “created and/or propagated” fake news of government accreditation, which confers access to official buildings and events.

Mainstream news organizations said the accreditation is necessary for reporters in the capital, New Delhi, to do their jobs — and the blacklist would effectively allow the government to control which journalists get access to news.

Critics said the policy, which did not define what news would be considered “fake,” could have been used to stifle coverage critical of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government.

Shekhar Gupta, a prominent print and TV journalist, called the measure “a breathtaking assault on mainstream media” that recalled efforts by a former prime minister, Rajiv Gandhi, to impose a draconian defamation bill in the 1980s. (Gandhi withdrew the bill.) Mamata Banerjee, leader of West Bengal state and a leading Modi rival, called it “a brazen attempt to curb press freedom.”

India’s information ministry withdrew the measure by lunchtime — but by then it had already renewed questions about freedom of the press in the world’s most populous democracy.

Under Modi’s powerful Hindu nationalist government, stories that challenge his allies and policies have been met with threats, lawsuits and cries of “fake news.”

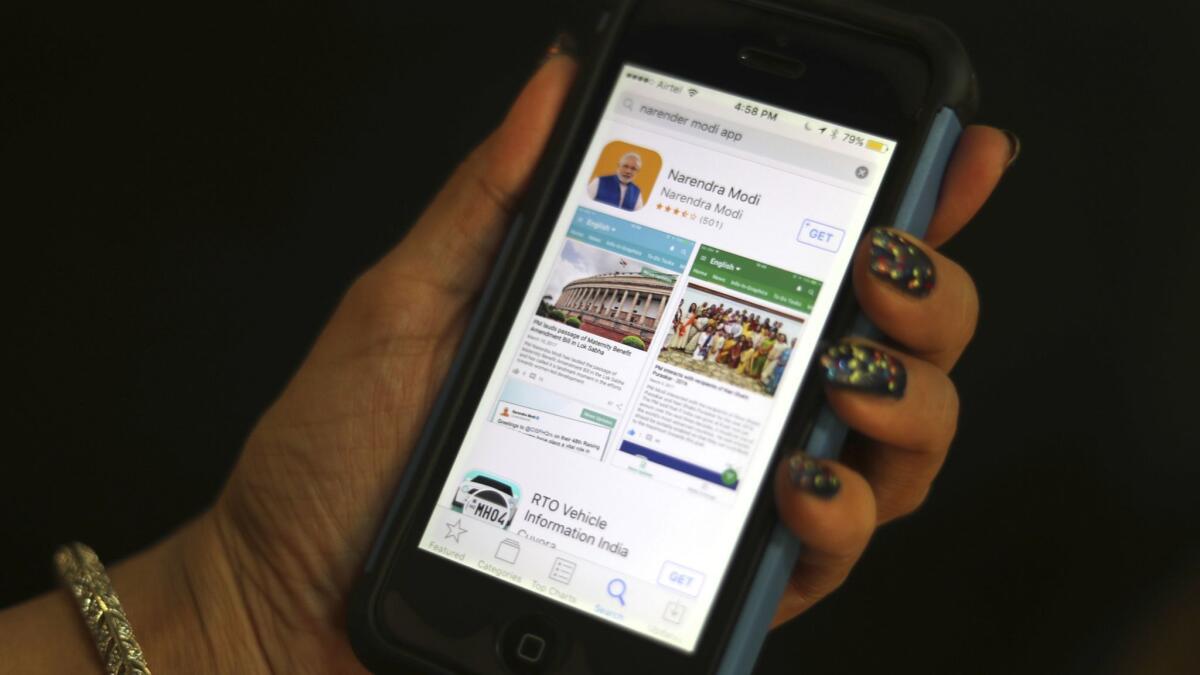

Modi, who took office in 2014 and is expected to seek reelection next year, has actively avoided mainstream journalists and hasn’t held a news conference since becoming India’s leader. He has preferred to reach supporters through his official app — which has been downloaded more than 5 million times — and his Twitter feed, which has more than 41 million followers, the most among world leaders after President Trump.

But as many as 60% of Modi’s Twitter followers are believed to be fake. And his government has a history of spreading misleading information, which journalists said made it a bad judge of what constitutes fake news.

Modi’s science minister recently claimed that ancient Hindu texts had a theory superior to Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity. In 2015, the government information office released a clumsily Photoshopped image of Modi surveying flood damage.

And Modi once told an audience of doctors that ancient Indians practiced plastic surgery — how else to explain Ganesh, the Hindu god with an elephant’s head atop a human body?

“When a government and ruling party that themselves peddle disinformation now say they want to fight fake news, it is time for the media to batten down the hatches and prepare for the worst,” wrote Siddharth Varadarajan, cofounder of the news website the Wire.

The four-paragraph government notice said any complaint would result in a journalist immediately losing accreditation pending an inquiry. Allegations against print journalists were to be decided by a council whose budget is controlled by the government, and for television journalists by a voluntary association of broadcasters. The measure would not have applied to digital media.

If found guilty, a journalist would have been blacklisted for six months for a first offense, one year for a second and permanently in case of a third.

Following the outcry, the information minister, Smriti Irani, tweeted that the guidelines had “generated debate” and she was “more than happy to engage” with journalist groups to “fight the menace of ‘fake news.’”

“I think the government realized its image would take a beating nationally and internationally,” said Rajdeep Sardesai, a TV anchor and consulting editor at the India Today news group. “And they also realized it was malafide and could be struck down in a court of law.”

By aiming at journalists’ accreditation, Sardesai added, “the real message was that we have the power to suspend you if you fall out of line.”

President Trump popularized the term “fake news,” using it to dismiss stories that paint him in an unflattering light, but the phrase has gained currency among authoritarian governments in Asia.

This week lawmakers in Malaysia passed a bill that makes disseminating misleading information a crime punishable by up to six years in prison and a $120,000 fine. Critics said the law could quiet coverage of a massive corruption scandal implicating Prime Minister Najib Razak. A parliamentary committee in Singapore is also considering anti-fake-news legislation.

In India, where hundreds of millions of people have gained Internet access in the past few years, social media apps such as Twitter and WhatsApp have become vectors of false or half-baked information, often published by websites claiming to be legitimate news organizations. Much of it promotes nationalism and Islamophobia and directly supports Modi’s agenda.

Last week, a government supporter and founder of one of the most popular fake news sites, Postcard News, was arrested in the southern state of Karnataka, which is led by a rival to Modi’s party.

Pratik Sinha, cofounder of the fact-checking site Alt News, said fake news in India had “reached epic proportions” but criticized the government for issuing “a four-paragraph press release without even defining what the issue is.”

“To me, it looked like an attempt to muzzle the press ahead of the 2019 elections,” Sinha said.

Parth M.N. is a special correspondent.

Shashank Bengali is South Asia correspondent for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @SBengali

ALSO

Fake news fuels nationalism and Islamophobia — sound familiar? In this case, it’s in India

Muslims faced hatred and violence in Sri Lanka. Then Facebook came along and made things worse

On Twitter, fake news spreads faster and further than real news — and bots aren’t to blame

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.