After Sri Lanka attacks, Muslims face calls to avoid mosques and remove their veils

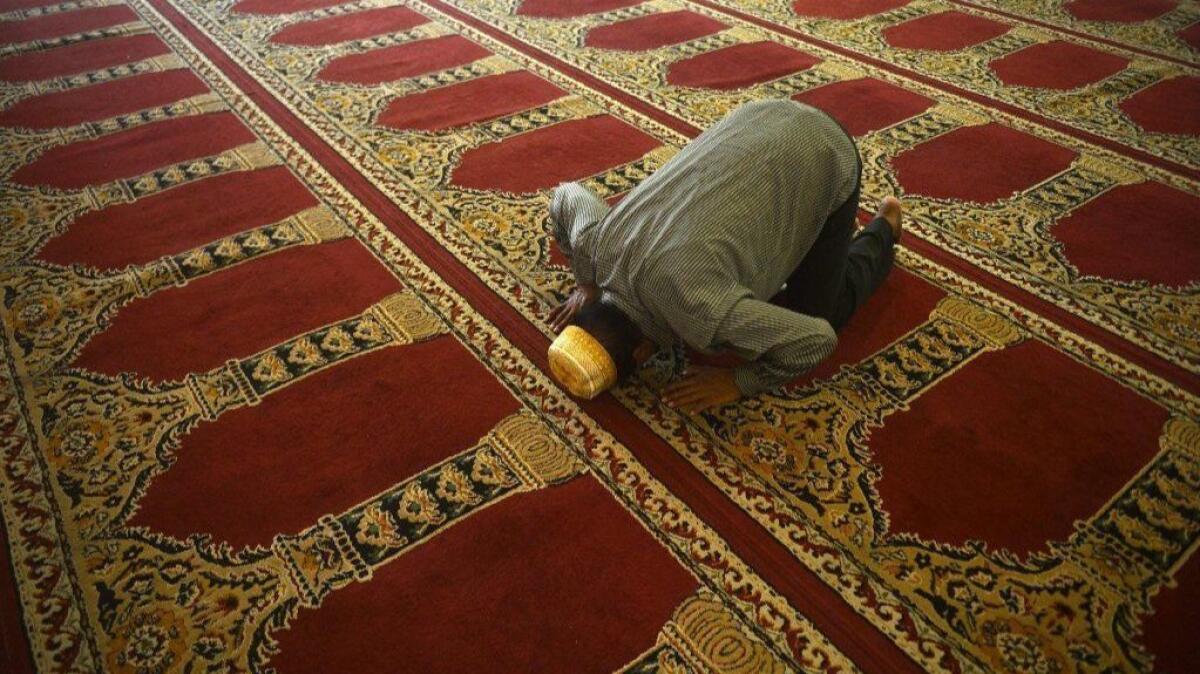

On the first Friday after the deadly Sri Lanka bombings on Easter, the island’s mosques were somber and surrounded by police and army personnel for the communal day of worship.

The few faithful who attended services at Dawatagaha Jumma Masjid — a landmark white-domed mosque rising from central Colombo like a wedding cake — emptied their pockets and opened their purses before entering for the communal prayer.

On the patterned red and yellow carpet inside, there were nearly as many television cameras as worshipers.

As officials warned that dozens of suspects linked to Islamic State extremists remained at large, Sri Lankan Muslims were on edge like the rest of their countrymen but divided over how to respond to one of the worst terrorist attacks in their nation’s history. At least 253 people were killed in the bombings Sunday.

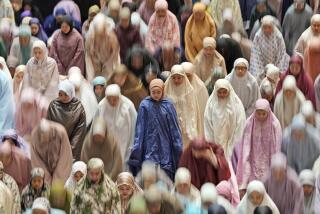

Many heeded the calls of religious leaders not to attend Friday noon prayers — the most important gathering of the week for devout Muslims — but to worship at home instead. The message was seen not just as a show of respect to Christians who were killed and injured in the blasts at churches, for which Islamic State claimed responsibility, but also as a security measure in case of another bombing.

“My belief is that a religious center should never be closed at any time as peace starts from there,” said Imthikab Cassim, a consultant in Colombo, the nation’s capital. But he called the move “practical.”

Others chafed at demands by clerics, public officials and some businesses that women temporarily stop wearing the Islamic face veil, or niqab, to assist security forces in conducting identity checks. Some women said they’d been asked to remove the veils and head coverings — worn to protect modesty — before entering shops, banks and hospitals in recent days.

The bombings have again exposed the tenuous position of Muslims in an overwhelmingly Buddhist country with a long history of ethnic and religious strife.

Muslims, who make up about 10% of the population of 21 million, have rarely clashed with Christians, a slightly smaller minority. But they have frequently been harassed and attacked by radical Buddhist nationalist groups whose influence has grown in the last decade.

Police confirmed Friday that the alleged leader of the attacks, a radical preacher named Mohammed Zahran, died in the blast at Colombo’s Shangri-La hotel, one of six hotels and churches targeted in the bombings.

Zahran was pictured in a video of the purported bombers released this week by Islamic State. He was the leader of an offshoot of the Islamist group National Thowheeth Jamaath whose venomous speeches against non-Muslims, spread in Quran classes and on social media, had been reported to the government by Sri Lankan Muslim groups years ago.

Late Friday, security forces were locked in a shootout with suspected militants in Kalmunai, an eastern coastal town about 20 miles south of Kattankudy, Zahran’s hometown. Sri Lankan news media reported that the suspects were connected to Sunday’s attacks and that multiple explosions had taken place, but there was no immediate word on casualties.

Muslim community leaders have pledged to cooperate with law enforcement agencies and expressed solidarity with the blast victims, saying that none of the bombers’ bodies would be buried at Muslim cemeteries. President Maithripala Sirisena called on Sri Lankans on Friday “not to look at our country’s Muslim community with suspicion, fear or distrust.”

“You must keep in mind that not all Muslims are terrorists,” Sirisena said. “It is only a very small minority who are linked to such a barbaric terrorist organization.”

As in many countries, Sri Lankan Muslims have grown more conservative, the niqab and body-length black abayas more visible now in laid-back Colombo and other cities than they were a generation ago.

Social media has fanned Islamophobia by circulating vicious anti-Muslim rumors — that mosque renovations have cut down Bodhi trees, sacred in Buddhism, or that Muslim shopkeepers lace food with chemicals to render Buddhists sterile.

Khansa Nalir, a business development manager in Colombo, said she feared that Islamophobia was rising again. But she has decided to stop wearing the veil for the time being.

“Right now, our country is under security threat, and we have a lot of people hurting,” she said. “So if the people who are hurting feel better if they see less of people wearing black [face coverings], I think we should do it.”

Colombo homemaker F. Razik, who asked that her full name be withheld, said she has worn the veil for the last decade but always removes it when asked by security forces. She once showed her face to a male immigration officer at the airport, in violation of conservative Islamic beliefs, when a female officer wasn’t around, she said.

“I’m willing to cooperate anytime for security reasons,” Razik said. “But not allowing us to wear what we’ve worn for years is a violation of my rights and is not fair.”

Some Sri Lankan women shared stories on social media of how they were treated for wearing Islamic garments in public.

One tweeted that she was not allowed into a government-run health clinic because she was wearing a head covering, though not the veil, and that employees “need to understand the difference.” Another said a security officer at a supermarket asked her to remove her hijab because it was making other customers “afraid.”

“I swear, it may be the same eyes who looked at us before, but there is a completely different perspective now,” she tweeted.

Special correspondent Mushtaq reported from Colombo and Times staff writer Shashank Bengali from Singapore.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.